Leaving Calcutta

Home

● Sitemap ●

Reference ●

Last

updated: 11-March-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

The

political changes in 1940s Calcutta, such as independence and partition, led to many leaving the city. It is in their minds that the city they knew

and so often loved lives on.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Leaving Calcutta

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

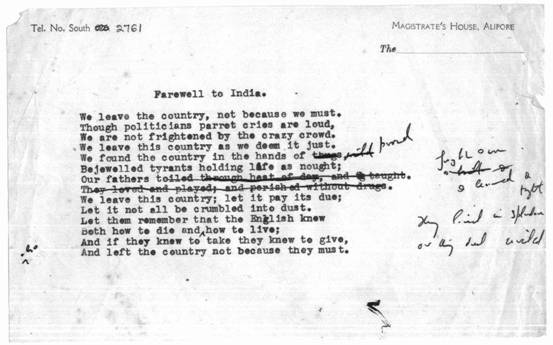

Farewell to India

Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart,

I.C.S. (Indian Civil Service) District Magistrate 24 Parganas, Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005 /

Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s

Calcutta___

Packing up

March 11, 1946

Dearest Ritter:

This has been a very busy day for me...too busy, and after about one more of these, I expect to take it easy from now on. Odds and ends at the office until about 10:30, then to Hindusthan with the Message Center boys. From Hindusthan I walked slowly along Chowringhee carefully looking over the motley scene that won't be a part of my life much longer. Down by the Lighthouse movie theater, seven coolies were carrying an upright piano on their heads. Irresistible. Well, not irresistible exactly, for I didn't do it, but I did have the impulse to trip one of them, say the corner one, to see what would have happened.

At Hogg's market, better known as New Market, but more apropos in its correct appellation, I paused for awhile in one of the shops that I have dealt with before, and lo and behold, I bought more and more, until I had completed my Indian buying right then and there. I now have your May 16, 29 and July 3rd gifts, as well as a variety of objects that the folks have expressed a desire for. Incidentally, dearest, don't open your July 3rd gift, though I hope to be there to keep a watchful eye on you. They are closing out some of their ivory, or say they are, so I ended by buying Mom and Dad a whole menagerie instead of the big ebony elephant that I originally had in mind.

After my shopping spree, I walked to the Cathay and had a quiet little lunch by myself, consisting of sherry, egg and vegetable soup, and egg too young. By taxi back to the hospital. The assistant driver had to get out and push to get it started and when we stopped at the entrance to the hospital (for taxis still are not permitted inside, for good and sufficient reason), I asked the driver if it would go. He looked around and grinned, his head wrapped in an absurdly long dishrag, his regular features stamping him a warlike Sikh (there are some races that look out of place in a taxi!), then bowed his head, placed his fingers together in an attitude of prayer, glancing my way to make sure I was enjoying the spectacle. But it was to no avail, for when he pressed the starter, there was only a whirrr.

This afternoon was spent writing my report, a history for the month of January. Casey, my bearer, and I packed most of my things, borrowed from AOD (Acting Officer on Duty) Munsen's jeep, and took them to Dahkuria, where Casey made my bed and deposited my huge new bag under the bed. Incidentally, I can just lift it, and that is all.

Whereupon came a disappointment: Parrish and I did not find our names on the shipping list for the Jumper. Now don't get upset, for if we miss it, we will make the Cardinal. Nevertheless, after all the rushing around, it would be sort of like the army to not have meant it at all.

As I have said before, if you should not hear by cable from me again, you may be sure that I made the Jumper, otherwise I will cable you exact information as to what and when. But this time I will wait until I know for sure.

I hope that your next letter assures me that you are in excellent health, and that all is well.

Much love, darling. You will get all the attention you can bear one of these days, and there will be no letting my darling do without whatever her heart desires. My kisses on your lips,

Dick

Richard Beard, US Army Lieutenant

Psychologist with 142 US military hospital. Calcutta, March 11, 1946.

(Source: pp. 296 ff of Elaine Pinkerton (ed.): “From Calcutta With Love: The World War II Letters of Richard and Reva Beard” Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2002 / Reproduced by courtesy of Texas Tech University Press)

On the ship home

Bay

of Bengal

March 27, 1946

Dearest Ritter;

I love you, precious, and wish that I could write more encouraging news, but we will have to take comfort in the fact that I am on my way home, even though I am stuck on a tub that is travelling only 10 miles an hour. If luck is with us, this letter should reach you by airmail from Singapore, but the mail situation is bad here, and there is a good chance that I may beat this particular message home. I am writing the folks, also, hoping that at least one letter will reach home in time to constitute news.

The way things have turned out, I have continued regularly to supply you with false information, but you must know that I believed it at the time. This ship never had a chance to get to San Francisco in 21 days. On its last trip, when its engines were functioning properly, it took twenty days to go from Singapore to Frisco. Here is the trouble. A bearing has been overheating, and they have cut out one engine, reducing our speed almost in half, so that we make out less than ten miles an hour, or only 250 miles a day. Since this is a ten thousand mile trip, it is easy to see how much time will be required unless the repairs, which are to be made in Singapore, are successful. No matter what, I doubt if I get home before the first of May.

Life for an officer aboard the ship is easy, by comparison with the enlisted men. I share a cabin with eight officers. Our beds are comfortable, mattressed, sheeted, pillowed, and we are supplied with free towels. We share a bathroom with another group of men from an adjoining cabin. The officers have the best space on deck reserved for them, and I have been doing a lot of sunbathing. My work is light, having been assigned as a compartment officer in C-3 hold (which is similar to the one I came over in).

The meals are out of this world. We are served by civilians on table-clothed surfaces, in plenty of dishes, with three courses usually constituting the meal. The food is very good, and I should fill out my cheeks a little. So far no poker, and I doubt very much if I play at all, since the only game going is financed by the merchant marines, and is crooked.

A number of 142nd enlisted men are aboard, as well as Just, Parrish, and eleven nurses. Of the 70 women on the ship, 42 are Red Cross, 16 war brides. I haven't seen any attractive ones yet...suspect that there is only one attractive woman in the world for me anymore, and you should know her very well. It is hard waiting to hold you in my arms, but with each day my ardor grows, and darling, that will be a wonderful moment...all moments will be wonderful from then on.

Your loving husband,

Dick

Richard Beard, US Army

Lieutenant Psychologist with 142 US military hospital. Bay of Bengal, March 27,

1946.

(Source: page 297 ff of Elaine Pinkerton (ed.): “From Calcutta With Love: The World War II Letters of Richard and Reva Beard” Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2002 / Reproduced by courtesy of Texas Tech University Press)

Whales and the Pacific

En route to ZI

Pacific Ocean

Above Wake Island

April 12, 1946

Dearest Ritter:

Excitement! Excitement! Whales and ships.

Early this morning, I must have been awakened by a flashing

that came in through the porthole, for I got up to see lights answering - the

flashes upon the water apparently the reflection from our own signaling lights.

Ships that pass in the night. This morning we encountered another...an

interesting sight out here, for the ocean is so vast that one rarely ever sees anything

except this big spot of mouthwash saline solution.

This morning's ship was an American freighter.

But the most interesting sight was our encounter with literally dozens of whales. We first noticed the mammals just after breakfast, when we saw a series of spouts off the port. Occasionally the back of one of the whales could be seen, as they sported with one another. But the real revelation came when the whales came closer to our starboard side...no more than 100 feet away.

I

saw as much as 15 feet of the backs of the huge animals myself. They do not

swim very high in the water, but undulate like the porpoises. We passed the

school about 0930. In the afternoon, while I was

sleeping, we came into another school of them, striking one big fellow - according

to several unreliable witnesses.

Floyd McDonald and I played a number of games of gin rummy,

this time correctly, for that Rous kid didn't

know what he was talking about -- with me edging over him just a trifle. I like

that game, by the way.

We saw a movie in what is turning out to be rather cool

weather for those of us with the watery blood of India in our veins. The movie

was "Uncle Harry." Geraldine Fitzgerald has several remarkable

scenes, and shame on Ellen Raines for walking (slinking) into a room that way!

We have been kidding quite a bit about our second Saturday

this week, and tomorrow is the day after, you know, and that sort of thing.

Incidentally, no one seems sure as to whether those are gulls, terns, or albatross

following the boat. I did a little checking on our situation, and we are quite

away to the east and north of Wake.

Love,

Dick

Richard Beard, US Army

Lieutenant Psychologist with 142 US military hospital. Pacific April 12, 1946.

(Source: pp.364-65, of Elaine Pinkerton’s proposal for Elaine Pinkerton (ed.): “From Calcutta With Love: The World War II Letters of Richard and Reva Beard” Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2002 / Reproduced by courtesy of Texas Tech University Press)

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

“…

a cold dark land - 'Blighty'”

I

left West Bengal at the end of 1949, we (the Miln's) sailed from Diamond Harbour on the British India

steamship "Kargola' bound for Falmouth, England. It took me, and my parents, a number of years to 'partially’ adjust to living in a cold dark land - 'Blighty'.

Kenneth Miln, son of a ‘jute

wallah’. Jagatdal/Calcutta, 1945-49

(source: Letter sent to

us by Mr Kenneth Miln himself, July

2006/ Reproduced by courtesy of Kenneth Miln)

“…

I miss the Bengali folk …”

I missed, and for that matter still do, the year round 'tamashas', the wonderful tropical 'bagans' full of brightly coloured butterflies - and interesting snakes! Last but by no means least I miss the Bengali folk , they were a real delight - 'THE OLD CALCUTTA WALLAHS.

Note: I have, since the 'old days', visited Calcutta - Kolkata - many times ; most recently during 2002. Although a great number of changes have taken place, and still are, I feel that 'CAL' will continue to retain much of the "old atmosphere' for many years to come.

Kenneth Miln, son of a ‘jute

wallah’. Jagatdal/Calcutta, 1945-49

(source: Letter sent to us by Mr Kenneth Miln himself, July 2006/

Reproduced by courtesy of Kenneth Miln)

She came down to the docks

with me.

She

came down to the docks with me. My exceedingly small L.S.T. was almost ready to

put out for the long journey. It was the same farewell as always: the bright,

uneasy chatter, the beating heart, the false bravado.

'Just

remember ,..' she fiddled with the buckle of her sandal which had come undone,

'.,. just remember. I'll be going home in about a month, I think . .. you have

my address. . .my sister's house ? Well, it's just that when you get back, if

you need anything, or if there is anything I can ever do, just... well just.

-.' the buckle came off in her hand. Hell! Now I'll have to hop about looking

for a taxi. But I mean... if you want me, give me a call...'

Dirk Bogarde, Air

photographic intelligence officer. Calcutta, late 1945

(source: pages 138-145, Dirk

Bogarde: Snakes and Ladders London; Chatto & Windus, 1978.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Dirk Bogarde)

by instructions to get packed

ready to travel to “God Knows”

In typical R.A.F. fashion, our peaceful existence was

rudely interrupted by instructions to get packed ready to travel to “God

Knows”. This was followed by yet another train journey which made our 5 day one

seem like a mini trip. This was followed by a short sail up the Brahmaputra and

yet another train journey to a place called Dimapur. From there followed a 100

mile road journey to Imphal in the Minapur state.

Jim Homewood, Royal

Air Force, Calcutta, May 1942

(source: A5760281 My War - Part 3 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Dorothy could not stand the

cold

They came back to England several times but Dorothy could not stand the cold and the damp and always went back to India. On her last visit to England in the sixties she developed Pneumonia and once she recovered they went back and Burra-Aunty died at the age of 85 in Calcutta.

Dorothy last worked as the school secretary at my old school La Martiniere - and she was well into her seventies. I think she only left when about 78 or 79 due to the fact that she could no longer see.

Elizabeth James (nee Shah),

AngloIndian schoolgirl. Darjeeling, 1947

(source: page 38 Elizabeth James: An Anglo Indian Tale: The

Betrayal of Innocence. Delhi: Originals, 2004 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Elizabeth James (nee Shah))

Escaping India to Europe

By July 1945, the war with Germany being over, my father decided we should return to the U.K., as at that time India, politically, was in turmoil. We sailed from Bombay on the "Johan an Oldenverd", a Dutch vessel manned by a Javanese crew. This again was a troopship with returning servicemen, many of the officers accompanied by their brides. We were allotted a cabin holding 30 women and children. It was very overcrowded and so hot and stuffy that many of us slept on board until we reached the Mediterranean. We had travelled all round the Cape and now returned via the Suez Canal - this time only taking three weeks.

Mary Anderson (nee Hezmalhalch), schoolgirl, Calcutta, Summer 1945

(source: A2640601 A Schoolgirl’s War in the Far East at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Demobed away from Eunice

At the end of the war huge numbers of servicemen were applying

for and being granted their demob whilst still stationed abroad, having found

employment or girlfriends there. This situation was becoming such a problem

that in the UK the parents, and in some cases the wives, of servicemen were

complaining to the War Office that their men folk were not coming home. As a

young man I had no dependants at home and had met and become attached to

Eunice, the daughter of a local Police Inspector, who had been born in

Calcutta. I had also been offered employment on a local plantation which I had

accepted and intended to take up after my demob. I think my romantic letters to

Eunice hastened my end in Calcutta. It was at about this time that it became

orders that servicemen had to return to the UK for their demob, brought in, no

doubt, in response to the many complaints the War Office had received. Anyone

wishing to return abroad like myself would then have to pay their own passage

and accommodation. My life could have taken a very different turn if my demob

had been a few weeks earlier.

As it was three of us picked up our rail vouchers for the

three-day rail journey from Calcutta to Bombay, eating and sleeping on the

train. We stayed for about two months in Bombay in 1946. I remember the city

appeared cleaner than Calcutta and there were fewer beggars, and whilst there

we became involved in the Indian Navy mutiny. One day we were detailed to block

all the roads leading from the harbour to the town. This would have been fine

had we been armed but our only defence against mutineers carrying weapons were

pickaxe handles. The officer in charge waved his about so wildly we felt we

were more in danger of being wounded by him than by the mutineers.

Eric Cowham,

Royal Navy, Calcutta & Bombay, 1946

(source: A7229856 HMS Tyne, Burma and India at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

My hopes of being able to

stay in Cal were dashed

My hopes of being able to stay in Cal were dashed, I was

posted to a newly formed unit called "The Jungle Target Research

Unit", somewhere in the wilds of Assam, and goodness knows what it was all

about.

Cliford Wood, Royal

Air Force wireless operator,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4254103 AN RAF WIRELESS OPERATOR ON THE BURMA FRONT (Part 3 of 3) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

"pack your kit you're

off tomorrow."

Then it all started again "pack your kit you're off

tomorrow." Where ? I never knew, Kandy, Trincullee, wherever the

Mosquitoes went, I went, flying once (in a two seater aircraft) with four

blokes packed in, with me sat on top of the radio, the rest in the bomb bay,

anywhere ! I stayed ‘attached’ to the Fleet Air Arm and then was flown back to

Alipore. But no rest for me. I was given a train ticket and a week’s American K

rations with free cigs (though I never smoked), unarmed and flying with unarmed

aircraft. I stopped sometimes long enough to get boiling water for the soup and

to brew the K ration tea. Finally at the end of the West Coast Indian Railway

it was off on a ferry crossing to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). A few days then at

Trincullee and the Royal Navy (I got rum ration there too).

Philip Miles, RAF photo reconnaissance unit, Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source: A4144664 What did you do in the RAF, Dad? (Part 2) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Leaving for the Cocos Islands

But soon the Mosquitoes were off again to the transit camp

in Columbo where I turned up with my orders and my credentials. As usual they

knew nothing about me, who I was or what I was supposed to be doing there. So I

spent a nice time on the beach and in the town and no-one asked why. They just

gave me a bed and plenty to eat and that was about it, the lone ranger again.

After a week or two the transit camp sent a truck and told me there get all

your kit ready you're posted to the Cocos Islands to replace a bloke who crash

landed there. He was the only one of the crew that survived. When you get there

he can go home. "Good,” I said, "never heard of the place, how do I

get there." "Now there's the snag," he said, "a boat calls

there with supplies once a month, so you're stuck unless something else turns

up." Another week and something did turn up, an RAF Liberator Bomber was

flying out to Australia and is refueling on the Cocos Islands. If I could get

my travel pass signed by a ranking officer I could get on it. I would be able

to nip off whilst the Lib refueled. Well I had my pass and I only need it

signing.

I knew the HQ of South East Asia was at Columbo, there must

be some high ranking officers there. So I presented myself in my still CPL

Miles uniform and passed the armed guards who saluted and let me through. I

went up to the desk and the bloke at the window pushed a list of officers

through to me and said who do you want to see. I did a quick scan and picked a

Wing Commander (I've since forgotten his name) I have to see him I said. “Yes

sir. On the 3rd floor just ask up there.” So I did (good job I wasn't a spy).

On the 3rd floor I met an Indian army girl, a WACC. She had a tray with cups,

plates, sugar and biscuits she looked at my pass to see the Wing Commander and

said, "Oh I'll save you the trip, wait here I’m just about to take him his

tea. A few minutes after that she returned with a signed pass. And off I went

as fast as I could, to get out of the building before anyone asked me any

questions.

I turned up with my pass at the Transit camp, "Right come back on Wednesday and we'll take you to your plane, bring all your kit and don’t say where you are going." (I didn't know anyway so I couldn't tell anyone). Calcutta International Airport was (and still is) in Dum Dum; just outside the city. There was my plane parked in the lay by and I was told to go aboard and wait. When I climbed on board surprise, surprise, this was no ordinary bomber it was fitted out like a transatlantic airliner ! Complete with radio, books and magazines and a stewardess who showed me to my seat. I was all alone, no passengers just me. Then things happened , a couple of posh cars rolled up with flags on the front and out came 6 officers who were shown to their seats by the stewardess (but not next to me). And within a few minutes we were up the main runway and we were off.

Philip Miles, RAF photo reconnaissance unit, Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source: A4144664 What did you do in the RAF, Dad? (Part 2) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

I ended with a love /hate

relationship

By

now, I was anxiously anticipating news of repatriation. My overseas tour had started

in November 1941 and I could thus hope to be in the boat by the end of 1944. I

had started by loving India. I ended with a love /hate relationship which seems

to be the common experience of most white Britons. My overseas tour had been,

at the same time, the unhappy time of my life, the most exciting, the most

dangerous and a tremendous experience I could never forget or regret. The

friendships I made were mutually sustaining and from the "NICE"

British in India I received much pleasure and help. When your life has been in

danger and you have experienced what it is like to be "without", when

you have been cut off from loved ones and when you have been subjected to

differing ideals and ways of behaviour, it is not to be expected that you will

come back home the same person you were when you left. My religious beliefs

were in tatters. All the business of a Divine Being who even watches over a

sparrow could hardly stand up to my experiences of the Bengal famine, not to

mention every day Indian life. A man who was "Right Wing" politically

couldn't survive with the same beliefs in view of the inequalities and class

bias of the forces, politics and wealthy colonials - and the often incompetent

and appalling leadership of those "born to lead".

So! Eventually the call came and in November I was back in Barrackpore briefly for the formalities of repatriation. From here, another four day rail journey to Bombay. Then a week of waiting at Worli camp and then through the "Gateway to India" and on to the "MOULTAN" and farewell to India.

Harry Tweedale, RAF Signals Section,, Calcutta, 1944

(source: A6666014 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 13 Pages 100-108at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

I symbolically threw my Topie

overboard

So! Eventually the call came and in November I was back in Barrackpore briefly for the formalities of repatriation. From here, another four day rail journey to Bombay. Then a week of waiting at Worli camp and then through the "Gateway to India" and on to the "MOULTAN" and farewell to India.

Two things above all I remember about the "Moultan". One of its funnels was much bigger than the other and the other thing - the bread - newly baked daily - wonderful!

Across the Arabian Sea into the Red Sea where I symbolically threw my Topie overboard, and into the Gulf of Suez.

Of course, nothing goes straight forwardly in the forces and at Port Taufiq, just before we entered the Suez Canal we had to change ships. We were now on the larger and more modern "Strathmore" but not as comfortable as the "Moultan" and with a less efficient baker.

Through the Suez Canal, with the curious illusion that we were moving through the desert without any water around, and on Christmas Eve we arrived at Port Said. Christmas Day laid up but no more shore leave. Then, on again - the roughest sea of the journey was the Med. - and New Years Day in Gibraltar. No shore leave again. Not that we really wanted it. We didn't want to risk being left behind.

Harry Tweedale, RAF Signals Section,, Barrackpore to

Liverpool, Nov 1944

(source: A6666014 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 13 Pages 100-108at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

I couldn`t raise that arm to

salute properly!

At the same time my injured arm was playing up - I said

that I would have to be demobbed because I couldn`t raise that arm to salute

properly! I was sent home in 1946. I`m so tall that no demob suit could be

found for me; for formal events I had to continue to wear my officer`s uniform

for several months although I was a civilian.

David Ensor,

wireless operator with Royal

Corps of Signals, Calcutta, 1946

(source: A4255427 Early Promotion at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Flying Home

Red-letter day

Sunday, 6 December: A red-letter day — the

news of my long-awaited release has come through. There has been bags of joy in

the place today, matron being just as thrilled as I am.

Needless to say, I don’t know whether I’m

coming or going, but I’ve spent most of the day wangling a passage, and, thanks

to General Stuart, I leave for Karachi and Blighty, by air, tomorrow!

This really has been the most hectic 24 hours

of my life.

Last-minute everything

Monday, 7 December: Today has been a mad rush

of last-minute shopping, packing, reporting to collect my ticket and being

weighed-in by BOAC.

I spent my last evening with as many friends

as I could gather together at the Saturday Club, where we dined and danced. As

the plane takes off at the crack of dawn, it was not worth going to bed, and so

a party was held at the airport sick quarters.

Flying over India

Tuesday, 8 December: At dawn this am, our

Sunderland took off from the Hooghly. I must admit that I was too excited (and

tired after an all-night party!) to feel sorry at leaving Calcutta. It was a

grand experience crossing India by air, especially with the awful memory of

that train journey across it.

We landed on a most beautiful lake half-way

across for refuelling. It seemed more like an Italian lake than part of India.

We had lunch at the BOAC hotel on the shore. Later, shortly after tea-time, we

glided down at Karachi, my first thought being how much more pleasant is the

climate than Calcutta’s.

Karachi itself is a grand city. It seems so

clean. We are installed in a very nice hotel but horrified to find that we may

be here for a week before we get a plane to the UK — such an anti-climax for my

elated spirits.

Henrietta Susan Isabella Burness, V.A.D., Calutta to Karachi, early December 1945

(source: A1940870 Life in the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment), 1945at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Leaving to Assam

After several days at the camp,

during which he went again into Calcutta — principally to get some nice food —

your Daddy heard his name called out one morning at the Parade, and learned

that he had to catch a train at about nine o'clock next morning. He was all

ready at eight o'clock to catch a lorry which took him with some others to

Sealdah Station at Calcutta, where the train was, and this station belonged to

another line called the Bengal and Assam Railway. Off we went round about ten

o'clock, and for a long time travelled in much the same sort of flooded country

I have already described to you. We were now on the other side of the great

river Brahmaputra and occasionally could see it swirling along — a great muddy

torrent. When we had been in this train about six hours we got off at a station

called ???? and this was right by a jetty alongside the river. Here some

coolies carried our kit out to a big river steamboat which was moored

alongside, and we walked aboard over the gangplank.

By now it was about six o'clock and after casting off the

mooring lines from the shore, the steamer which had big paddle wheels to drive it

along, slowly got under way out into the muddy river, which was racing down

towards us at quite a rate.

Leonard Charles Irvine, 4393843, Royal Air Force

Flt Sgt Nav, Calcutta, 1945

(source: Leonard Charles Irvine "A LETTER TO MY SON" at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Leaving Calcutta on Guerilla

duty

On Saturday 31st October we were issued, that is the

wireless operators of our unit, with a document asking for volunteers to man

observation posts hundreds of miles away in the jungle hills of the Assam

Burmese border. If the Japanese advanced we were to stay until the last, then

take off and become guerrilla fighters under Army Officers and would become

part what was to be called a special "V" Force army. We didn't stop

to think what we might be letting ourselves in for, so we all volunteered and

I've got the document to prove it!

On Monday 16th November 1942, we left Calcutta for Silchar

in Assam by train, this was to be the start of what we had come all this way to

do.

Cliiford Wood, RAF Wireles operator, Calcutta, 1942

(source: A4254059 AN RAF WIRELESS OPERATOR ON THE BURMA FRONT (Part 2 of 3) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

"Anne Gidney's gone to

Sydney."

I was so shy and introverted that I had been in the school for six months before I even spoke to anybody apart from saying "Good Morning" or answering when somebody spoke to me. The first person to break through this shyness was a girl called Anne Gidney who must have been the loudest girl in the school. She came up to me at break time one day and said, "Everybody thinks you are stuck up because you do not speak to anybody but I've decided I am going to speak to you." She became a friend but unfortunately she left at the end of that school year and went to Australia. All the girls used to chant, "Anne Gidney's gone to Sydney."

Elizabeth James (nee Shah),

AngloIndian schoolgirl. La Martiniere for Girls, Calcutta, 1948

(source: page 48 Elizabeth James: An Anglo Indian Tale: The Betrayal

of Innocence. Delhi: Originals, 2004 / Reproduced by courtesy of Elizabeth

James (nee Shah))

By Convoy to Glasgow

Within three weeks, news came that a ship would soom be in Bombay, so I had to pull myself together for further aarduous travel. We caught the Bombay mail train for the journey across India. Having spent forty-three hours on the train, we arrived in Bombay and word came for us to board the ship. It was war-time and we really had an unpleasant voyage. We were on a Dutch liner which had taken troops to India in readiness for attacking the Japanese in Burma and the Far East. The boat was crammed with civilian refugees ordered out of that area of Burma, India and China. It was jammed with people. Andrew was in a cabin with nine other men. I had a small two-berth cabin with Heather and Monica, two other women and four children - nine of us in all. Heather and Monica had also developed whooping cough. When the children, in distress, were coughing ,these women swore. They were so rough and unkind. The nights were dreadful and I had little sleep. The crew were solely concerned with themselves, and I was not allowed to take the children to the dining room; nor was Andrew allowed to our cabin because of the other mothers. However, a member of the crew - a young black boy from Borneo - took pity on us and each morning he parked himself outside my cabin door, and when I opened it, ran off to fetch something for the children to eat.

Our ship crossed the Indian Ocean and through the Red Sea alone, as this Dutch liner was one of the most modern, and we depended on our speed to get us out of the way of danger. Each morning we had to line up for boat drill, and all day we had to carry life jackets everywhere we went. The children were given them too - adult sized! I wondered if there was anything I could do to make them fit, but it was hopeless. From time to time the crew also had firing practice, but the one ime they let off the big gun - although we had been warned - it gave me such an enormous shock as to be almost hysterical for the only time in my life. I had survived the threatening whirlpools of the Yellow River, had the windows of my bedroom blown in by bombs, seen bomb and gunfire all around me in China, walked alongside men with plans to end my life. resisted the terror of our flight over the darkened mountain peaks - yet all that did not break my nerves in the way that the thundering bang of this long distance gun affected me. I will never forget it. (Monica adds that her parents later told her that if anyone had fallen overboard into the sea, because of the great danger from U-boats the Captain would not have turned the ship around for any search or rescue attempt)

For the final lap of our voyage we were in a large convoy, with an aircraft carrier, all the 'Empress' boats, and others of all descriptions. We zigzagged along in our crocodile line, day after day. It was reported that a U-boat was near us, but still we pressed on...when would we see England? Andrew commented that we would soon be at the North Pole if we carried on in the same direction for much longer. Everything was veiled in secrecy. Up on the deck one afternoon, as I had got the children to sleep for a few minutes, I was standing by myself rather miserable, Just the, as one of the ship's crew walked past (who must himself been feeling fairly happy to speak to me!) turned and said, "Do you see those ships there in the distance? They left Glasgow this morning". Glasgow! So we were nearly home! We had travelled steadily northwards to come in around Ireland and into the Clyde. During the night I could tell we had stopped, and then in the morning - how wonerful to see the bare hills of Scotland on a January morning! We could not send any kind of message to our folks, and had to remain quietly on on board for three days, as Glasgow was teeming with refugees. One day, a gentleman came on board to inquire if anyone needed somewhere to stay in Glasgow, and so Andrew obtained an address from him. It was fortunate, for when the CIM representative met us in Glasgow he told us they were unable to accommodate any more as people were already sleeping on the floor. As a result we went to the address given to us. What a sight we must have looked, wearing old Chinese clothes. People turned to stare. I had got a coat in India, and a pair of shoes, but they still looked extremely odd in Glasgow.

Mary Kennedy(nee Weightman), wife of a missionary China

Inland Fellowship,

Calcutta to Glasgow, early 1940s

(source: A7091273 Escape from Chine (Part 3) Over Enemy Lines. at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Leaving Barrackpore

Things were beginning to change at Barrackpore and perhaps Darjeeling had made me restless. Sir William (Bill) Slim, Commander of the Fourteenth Army and Lord Louis Mountbatten (Supreme Commander South East Asia Front), gave us talks on their strategy. The tide was beginning to turn. In late March an advance HQ for RAF, Army and USAAF was to be established in a more forward position at Comilla, Assam. Postings were made to newly recaptured airdromes. New personnel at last started to arrive from England to fill the places vacated by old friends. Dan - time expired - went home via Bombay. Brian Wilson was posted to Ranchi. Bob Stannard to 222 Group HQ at Chittagong and Bill Kerr to Cox's Bazaar. I was beginning to find my extra "church duties" irksome in the heat and could no longer claim any strong religious conviction. Staff was beginning to be plentiful at Barrackpore after two years of shortage. I was told by P/O Parry that I was to be posted to Comilla to the new HQ to take charge of a traffic watch - but, in view of my extra connections at Barrackpore, he could fix it for me to stay if I wished. I kept this offer to myself as I didn't want the Browns and my other friends to think me ungrateful for the great deal they had done for me. I decided I would go " East of the Brahmaputra" - at least I should see more of the country.

Harry Tweedale, RAF Signals Section, Barrackpore, 1943

(source: A6665457 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 11 Pages 85-92 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Posted to China

After a while he was returned to Calcutta with Force 136 again, where he enjoyed playing football

and cricket. He was still not allocated to a special duty and after making

inquiries he was informed that he was still on the strength at Calcutta, but was awaiting a posting to China. This was a shock,

but he flew over the Himalayas in the company of an American F.A.N.Y (First Aid

Nursing Yeomanry) by the name of Rita. I think they were both apprehensive

about the flight, but landed safely at Kunming where Rita was stationed. He

travelled on to Hsi Shan by jeep. He was situated on the edge of the Yunnan Lake

in the house of a female missionary Miss Tindall. There were only about 20 of

them there. He enjoyed the time in China and was eventually demobbed from

there, flying to Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi and sailing on the Strathnaven, docking at

Southampton on February 12th, 1946.

Ron Maris, Royal

Corps of Signals, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A1980407 Extracts from My Life by Hilda Maris: War Years in Sheffield at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Recollections of the war -

R.W.T. Bridgman

When war was declared, I was living with my father, mother

and two sisters in married quarters in Calcutta. We stayed there

until May 1944, when my father received orders to return to England. We

eventually left in July 1944 as part of a convoy, aboard the troopship S.S.

Stratheden.

I remember looking out from our port side one day and saw

an aircraft carrier passing close-by. Aboard the aircraft carrier, there was a

funeral service taking place for two naval airmen who had crashed into the sea

in a Fairey Swordfish while patrolling the convoy, protecting it from Japanese

submarines.

We eventually arrived in Glasgow and we undertook a lengthy

train journey to visit my grandparents in Walkhampton, on Dartmoor in Devon.

While waiting for our final train connection in Plymouth, my father suggested

we stretch our legs and take in the views over the city. I shall never forget

the terrible sight of seeing the ruins of Plymouth city centre left over from

the aftermath of the Blitz.

R.W.T.

Bridgman, schoolboy, Calcutta, July

1944

(source: A2356760 Recollections of war: In London and Devon at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

We had berths on a boat going

to Britain

The next great memory was of March 1945 when there was a

lot of rushing about, a real hive of activity. We had berths on a boat going to

Britain; we were going home. My father was not able to go with us so my mother,

sister and I set off on what was going to be a long journey and a two year

separation from my father.

We travelled to Bombay by train for two days and nights and

there stayed with friends waiting to be given our tickets and to be told when

we would be able to leave. Everything was very hush-hush, but eventually we

were given our tickets and informed that we would be sailing on the S.S.

Multan, which turned out to be a gunboat protecting other ships in the convoy.

As you can imagine our parents were not too keen about his but all we children

on board were most impressed and excited. We were allocated life-jackets which

we children had to wear all the time. We would, naturally, remove them and

forget where we had left lthem so mother would have to take us all over the

ship looking for them. According to the officer who conducted our safety drill,

there was really nothing to worry about; he said that if anything happened we

would jump into the water, turn on the little red lights on our life-jackets

and along would come a British warship and pick us up out of the water, no

problem.

Some years later we heard that for most of the way home we

had been shadowed by German U Boats. We were safe while passing through the Red

Sea and the Suez Canal but once out of there we were watched by German subs

again. It took seven weeks to sail home and our final destination was kept

secret. However we sailed up the Clyde and moored off Gourock, right opposite

our aunt’s house which was to be our second home in the years to come. We had

arrived back in Britain two weeks before V.E. Day.

M Brown ,schoolboy, Asansol

& at sea, 1945

(source: A7468716 Wartime in India at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

We had to surrender our

British passports or ‘move on’

1949. We had to surrender our British passports or ‘move

on’ so my Father said we were going to England. We had to pay our passage to

Tilbury. My father brought a flat in London. It was hard for my Mother with no

servants and no idea how to cook, run a home, look after us all, cope with

money or rationing and come to terms with life in England and London. I went to

secretarial college, one brother to college and another became a naval cadet.

Dad then got a house in Archway, and all our crated possessions arrived by sea

from Calcutta

Dad worked in administration for telecommunications. He was

50 when we got to England and worked for about 15 years in the City

My boyfriend came over to England to finish his education

in Dunbarton, to become a Marine Engineer. We married in Highgate, and moved to

St Albans where my youngest son was born and have lived on Anglesey, before

moving to Shrewsbury, Shropshire.

Thelma Jolly, Schoolgirl , Calcutta, 1949

(source: A5230450 A Childhood in Burma at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

'for we're saying good-bye to

them all

…. the sea in the fading

tropic light, but strong with relief

that, the voices, a swelling

chorus to jeer us in ... '

'for we're saying good-bye to them all,

the long and the short and the tall,

you'll get no promotion

this side of the ocean...'

and five nights on another

train across the stranger-continent to Calcutta. Monkeys as well as parrots in

the banyan trees, Tagore's palace and the sudden monsoon, the rain falling like

steel rods, iced lime juice in the sticky heat of Green's Hotel, the gentleness

of the Indian, the startling, shameful, arrogance of the Memsahibs, midwives at

the abortion of an Empire; Truman's gesture to mankind and the pulverization of

two Japanese cities, branding forever man as the descendant of the killer ape.

And in the vacuum which followed, the

slow trip across tropical seas in an L.S.T. to an island bent on its own

self-mutilation in the name of Freedom. 'Merdeka!'the word to ring with fear

through one's head for months tocome. A world turned upside down, the values

back to front, the oppressed rising against the oppressor, all over again, and

with what results? New oppressors, new oppressed.

But now it was all over for

me at any rate, the brave new world lay all about me outside the windows, the

world to which I now must belong. The past was the past and all I had to worry

about was now.

Childhood had been easy,

beautiful,a glory ... unforgettable. Adolescence had only just started to offer

the most tentative of budding shoots when the burgeoning plant was culled,

bound, and trundled off in a 15-cwt truck from Richmond station into what were

now

quite obviously, the best years of your life. No good carrying any of this

stuff about with me like a bundle of crinkled love letters. Chuck it. The

hardest part was yet to come, the growing up; I was going to find it harder

than anything I had ever been called upon to do.

How do you, at twenty-six,

green as a frog, join the team with all the years since nineteen missing? Who

would care, or have the time ? Where would I go, and what would I do now ?

A sort of panic mounted.

Windlesham, if I was lucky. Little boys in grey flannels running up and down a

cricket pitch. Or I could work in a pub ... wait at table ... perhaps get a job

in a prison even? Something with men, something with the same sort of

background which I was now being forced to leave... could I get a job with the

War Graves Commission even Hopelessness

rose in me like a fever, I wasn't ready...don't get into Waterloo. . .don't

start my new life too quickly... I'm not ready, I don't know how to do it.

The man opposite, hit by my

unconscious kick, woke up and blinked. I apologized and he smiled through half

sleep.

'Nodded off,' he yawned and

stretched his arms wide across the near empty compartment, contentedly licked

round his stale mouth, belched gently and asked me where I'd been.

‘The Far East.'

'I could see you had a bit

of a tan ... Burma, were you?'

'Partly ... Malaya, you

know...' lamely, leave it, don't ask me. Tears aren't far…’

'Ah! The Forgotten Army, eh?

Well, you're safely home now, sonny. Mind you, we've had our problems, oh yes!

Not been easy. Dunkirk, the Blitz, and those V2s ... shit, don't , suppose you

know about them, eh? And the V1s, very nasty ... nearly did for us that lot

did. But we won, didn't we? We muddled through . . . can't say we didn't win in

the end.'

He smiled again, 'Course we

had Churchill, but he had to go; a bully... don't need a bully in peacetime.' He

pulled his mackintosh and a carrier bag off the rack, and stood at the door as

we rumbled into a platform. 'And,' he said with a wink, 'Waterloo's still here!

But we had a bloody awful war, mark my words, we was under siege, you know ...

under siege.'

'But you weren't occupied,

were you?'

He lowered the window and

thrust his hand out for the handle.'Don't follow?'

'Occupied. You weren't

occupied, were you?"

He swung open the door.

'Occupied ? This is Britain, mate.

Good luck!' He Jumped off

and ran along the platform before we had finally stopped.

Dirk Bogarde, Air

photographic intelligence officer. Calcutta& London, ca. 1947

(source:pages 68-69 Dirk

Bogarde: Snakes and Ladders London; Chatto & Windus, 1978.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Dirk Bogarde)

Millbrook

On the train from Southampton we rose from the dead

with the cars all in black and the buildings all red;

no Calcutta rickshaws, no Calcutta smell,

just old English junk-yards and adverts for Shell.

We halted at Millbrook, and there was a tree,

a green, weeping willow for Peter and me;

we watched as it blew in the pale English sun

and we knew from that moment the dying was done.

For surely Rangoon and Bombay were not real?

The charwallah cries and the Chowringhee meal,

the hangings in Bhopal, and in the bazaar

the loudspeaker music and GI cigar.

The white Capetown Castle, the orderly queue,

the bells and the whistles, the shouts of the crew,

the jokes of us servicemen, bawdy retorts,

the kitbags, the bush hats, the bleached khaki shorts.

'My name's Peter Watkin - there isn't an "s" ‘

said the chap with the violin case in the Mess;

and we slept on the deck as we sailed the Red Sea

and we talked about Beethoven, England, and Tea.

The pine trees in Simla, the shimmering snows,

the woodsmoke, the children, and God only knows.

The willow tree welcomed us back from the dead

as we pulled out of Millbrook, and not a word said.

Paul Wigmore, Royal

Air Force, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A2879274 Repatriation at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

The Old 'Koi-Hai’'

An

antique air surrounds his chair

in drawing room and club,

an old Koi-Hai, left high and dry,

a far away look in his eye,

and dreaming of the days gone by,

the good old days in Jub'.

The

leather tan proclaims a man

whose world has lost its hub:

no ready thralls to answer calls,

no boy brings whisky when he bawls,

stretched out at ease in marble halls,

as once in good old Jub'.

No

butler staid in gold brocade

to serve him with his grub;

no khidmatgar to bring cigar,

or fill the brown tobacco jar;

no chauffeur now to wash his car,

ho sweeperess to scrub.

No bhisti thin with glistening skin

to fill his morning tub;

no dhobi foots to iron his suits,

no beaters to attend his shoots,

no bearer to remove his boots,

or give his back a rub.

No

fellow bore to share the floor,

no crony at the pub;

no boy around to feed the hound,

no syce to bring the pony round;

no-one to meet on common ground

and no-one left to snub.

When

all is said—he's not yet dead,

he goes on paying his 'sub';

so please be kind and do not mind

if he continues to remind

us of the days he's left behind—

the good old days in 'Jub'.

R.V. Vernède, ICS, 1950

(source: page 261-262 R.V.

Vernède (ed.): “British life in India : An Anthology of Humorous and Other

Writings…” Delhi; Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1997.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Oxford University Press 1995)

Leaving Calcutta

Friends in R.A.F. Public Relations sympathized with my predicament, and I promptly applied for a transfer. After all, I was a writer of sorts and there was plenty for me to do in that line. Public Relations in India had been launched by the dynamic Brigadier Jehu and he needed fresh recruits. Wing Commander Falk hoisted me out of the Slough of Despond. The signal about my posting was held up for three weeks - I suspected out of malice - but I was released in October with a railway warrant for Delhi.

Harold Acton, RAF airforce

officer. Calcutta, early 1940s.

(source: page 117 Harold Acton:

More memoirs of an Aesthete. London Methuen, 1970)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Harold Acton)

I had become very fond of

India

I had become very fond of India and its people after all those years. I had found them good and understanding. They were, on the average, honest and good- natured - no matter in what walk of life - from the simple, working man to the wealthy maharajas, land-holders, and the big businessmen.

[…]

In all my years in India, I had found both Muslims and Hindus friendly and hospitable in every respect. I think I am correct in saying, however, that the Hindu was better educated and more genial of the two communities. Perhaps I formed this opinion because I had more dealings with them.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, 1947

(source: page 217 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

Leaving this ancient and very

friendly land

My retirement time in the Customs Service was drawing near. By 7th December 1944, I had completed my age limit of fifty-five years, but as the war with Japan was still on, I was given a year's extension. On the expiration of that, I was requested to do one more year - up to 7th December 1946.1 had kept in perfect health throughout my service, with the exception of the worry over losing my son Jim in March 1944.

In October 1946, I obtained two months leave prior to retirement and began preparing for my departure from India. At the end of October, however, I came down with a malaria attack and was obliged to go to the hospital. They put me right and I was out and about again by 15th November.

I sold my apartment with all its contents and shifted over to the Norwegian Reading Room so as to be ready for departure at a moment's notice. As all passages on the ships were booked months in advance, it was a very uncertain problem when passage could be obtained.

The Norwegian Consul then asked me if I would take up a situation with him as a clearing agent. He was a big businessman and had many interests, especially the import of paper from Sweden and Norway. Feeling fit and well after my stay in the hospital, I accepted his proposition and began work for him, intending to remain another couple of years in my beloved India.

The work in the Consulate was mostly in connection with the Customs and Port Commissioners, and it amused the Consul, Mr Gylseth, to see how I could clear cargoes through those departments in less than half the time it had taken his former agent. All went well and I saw visions of a better retirement financially after doing a couple of years more in India.

Fate willed otherwise. In January 1947,1 was again attacked by malaria, which pulled me down to a living skeleton. I told Mr Gylseth: 'There's only one thing this old wreck requires: it's a run to Europe to rebush all the worn bearings in my old cadaver. Get me passage by the first, incoming steamer bound for Europe.'

This he promised and, at the beginning of February, a Norwegian ship, the Konge Haakon VII, was due. When he showed me there were no passenger accommodations and, hence, no-one had been booked on it, I said: 'Don't worry, Mr Gylseth, there will be a hole in which I can fit in.' It turned out there was not one hole, but four - and I got one of them.

Mr Birla, on hearing I had decided to go away, sent word to me, so I called on him. When he saw my condition, he pleaded: 'Don't go to Europe in that state! Go up to my home in Pilani. There's the bungalow I built for your retirement some day. Go and stay there and regain your health. You are not in a fit state to travel to Europe. It's much too cold for you to go there after all these years in India!' I refused his kind offer, however, and took passage on the Norwegian ship.

As we sailed down the old Hooghly River, I looked with regret at the receding shores of this ancient and very friendly land which had been my home for forty-three years. Memories by the thousands flickered through my mind. On account of my illness, I had hardly been able to say 'goodbye' to anyone before departure, though I had been to the cemetery where lay my dearest treasure of all: my beloved first wife, the mother of all my sons!

Now there were only four sons left after the death of Jim, our third eldest.I had with me a bunch of roses and threw them overboard into the Indian Ocean near where his ship, the Nancy Moller, was sunk by the Japs on 18th March 1944.

I called to mind all the dream castles we had built the last time he was in Calcutta: how we would go home together in 1947 when his first six months' leave came due. I had waited for him for months after the sad news of his ship being torpedoed came to hand - and now, after all, I had to go alone, his remains lying in a watery grave about 300 miles from Colombo.

The whole of my life in this amazing country slowly passed before me, beginning with the hopeless feeling of loneliness which came over me when I learned the proud ship, Gogoburn, had sailed away and left me behind in the hospital in Calcutta... The pleasure of delight when I finally came out and found old, noble Captain Braddon had collected £12 for my sustenance on leaving the hospital... My trip to the railway station at Kharagpur to see if work on the Railways would suit me.

My application to the Calcutta Police, written by old Sergeant Jennings, and my being accepted there as a constable... My studying in the Police quarters, day by day, to perfect myself in English... The offer of marriage submitted to me through Mrs Boyles to marry a Bengali judge's daughter whilst I was on duty on Howrah Bridge directing traffic.

All passed as pictures on a screen: My great, lone fight on the crossing of Chitpur Bridge... My first run home to Denmark with an insane woman... And later, on my return, the Catholic priest who wanted me to save a sweet girl, who became my dear wife. All the weird and wonderful happenings of my stay in India passed before me as I sadly watched my beloved India growing fainter in the distance.

It would be hard to say which of my experiences was the most exciting - there were so many!

Epilogue

When he retired as Captain in the Customs Marine Department, Hansen returned to Denmark, where he settled down in Odense. He died on 2 October 1957

August Peter Hansen, Clearing

Agent, February 1947

(source: pages 217-219 of

August Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947”

London: BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

Our school was

closed down

Unfortunately for me this was 1947 and the year of

Independence. St. Michael's was a school of some 100 pupils headed by two Oxford

Mission Nuns and the teachers, etc., being extremely select. However, there

were very few Anglo-Indian girls and only two Indian girls so when Independence

was granted on 15 August 1947 our school was one of the first to be closed

down. I believe the building was eventually sold to the Turf Club and used as a

club. It was a most picturesque and truly English building with dark panelling

throughout set in sumptuous grounds. Darjeeling being very beautiful anyway and

flowers running riot there in the spring, summer and autumn - the gardens were

a sight to behold. Never again in my life have I seen such poppies, pansies,

violets and dahlias not to mention orchids which grew wild on the fences.

[…]

I loved my school and would have been happy to have stayed

there for the rest of my school career but the Indian Government had other

ideas- In the wake of Independence there was the Quit India movement and a wave

of hatred for all things which symbolised the British Empire. Our school being

one of these, it was closed down at the end of 1947 and that was the end of

that.

Elizabeth James (nee Shah),

AngloIndian schoolgirl. Darjeeling, 1947

(source: page 30 & 33 Elizabeth James: An Anglo Indian Tale:

The Betrayal of Innocence. Delhi: Originals, 2004 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Elizabeth James (nee Shah))

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

● Sitemap ●

Reference ●

Last

updated: 11-March-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org