Partition

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

● Sitemap

● Reference

● Last

updated: 19-May-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there are any technical problems, factual

inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then

please contact the group under info@calcutta1940s.org

Introduction

The

saddest side effect of Indian independence was undoubtedly the partition of the

country.

We start

the decade less than 30 years after the Swadeshi movement had re-united Bengal

against the will of the British colonial masters.

Yet

throughout the 1940s decisions were taken which drastically changed the

political landscape. The political consciousness of the rural Muslim majority

rose and felt unrepresented by urban Hindu majority Calcutta. This made it

possible for the Muslim league to persuade them of the potential benefits of a

separate Pakistan.

By 1947,

what in the late 30s had sounded like no more than eccentric ideas, had become

seemingly impossible to avoid.

The sole

remaining question, which for the future of Calcutta was vital and worried many

of its inhabitants very deeply, was how exactly Bengal was to be partitioned.

Was it

all, including Calcutta, to go to Pakistan, was it to be a separate independent

state apart from both Indian and Pakistan, or was solely the greater Calcutta

area to be split off to perhaps form some sort of neutral territory ?

Anxiety in

Calcutta and especially its Hindu community led to much agitation against

Pakistan.

In the end

as independence drew ever closer the province was cut in two (sometimes very

roughly) along communal lines, in less than a month.

India as a

whole and one of its most culturally distinct provinces, Bengal, was

partitioned, never to be re-united. The effects are stamped on to city and its

culture to this very day. Calcutta has

lost a large part of its economic and cultural hinterland, and countless of its

old and new inhabitants their homes and their roots, many even their lives.

Even

Ghandi who had done so much to ease partition in Calcutta in particularly was

had been murdered within a few month.

[Please

note that independence as well as the communal riots in 1946 each form separate

chapters]

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

The

partition

The partition of Bengal had caused many upheavals in our economic and political life. If you talk to anyone who remembers those times, you'll understand that the basic factor behind the economic collapse was the partition. I have never been able to accept the partition, not even today.

Ritwik

Ghatak. Calcutta, 1947s

(source: Recollections of Bengal and a Single

Vision at http://216.152.71.145/filmmakers/ghatak/ghatak.html reproduced from

the monograph Ritwik Ghatak prepared for the Festival of India in London, 1982)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ritwik Ghatak 1982)

The

Congress leaders never took the idea of partition seriously

The Congress leaders never took the idea of partition seriously. They couldn't believe that India would be partitioned and therefore my own opinion is that they didn't work at it. When it came it was too late to go back and fight it ... how the local communal troubles were stirred up by politicians or local thugs I don't know. How much it was because of the basic intolerance of the Hindu, not his aggression, but his non-acceptance of anything outside his caste - that's a very cruel aspect of Hinduism which people don't realise because it's a very soft and non-xenophobic religion but it's a very intolerant one - I also don't know. But I think that, politically, in the first thirty years of independence it was necessary for us to have a strong centre, though we have a fragile system. In Nehru's day the strength of the centre established us as a nation.

General

Palit,

(source: page 203 of Trevor Royle: “The Last

Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Original Ideas

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Jinnah Split

[…]

Socially, Indian Moslems are a solid,

self-conscious minority group (just less than

one-fourth of India's population) ; Hindus are a loosely-bound,

sect-split, caste-stratified majority

(three-fourths).

Hindus are the wealthier group. In general, Hindus

are landowners, capitalists,

shopkeepers, professionals, employers ; Moslems are peasants, artisans,

laborers.

In Bengal,

where Hindus are only 43% of the population, they pay 85% of the taxes.

One of the main reasons for this difference is

that usury, which accounts for far more

profit in India than trade, is forbidden to Moslems by religious law.

[…]

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Dec. 4, 1939)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

“Sthans and Isthans”

OF Pakistan we have heard much. Of Khalistan or Sikhistan, independent State for the Khalsa or Sikhs, and Zananisthan, Independent home for India's women where they shall be in direct obedience to the Paramount Power, but not to any husbands or other near authority, we have heard a little. Whispers tell of aspirations for an Achchutsthan for the Scheduled Castes and an Adibashisthan for the aboriginal peoples. All these in combination suggest that India will be well and sufficiently vivisected in the near future, and that the Office, must set up a number of new departments on its political side.

But there is more to come. A young correspondent has revealed what is going on in his sphere. "We, the students of India, view all this business of vivisection with undisturbed neutrality." As between Hindus and Moslems, wives and husbands, castes and outcastes, they are impartial and indifferent, having their own absorbing purpose to press on the authorities. In a few weeks, as soon as their university examinations are over (our correspondent, we regret, puts in a naughty adjective before "university") they will present their claim; not with humble submission as is duty bound, but as a demand not territorially limited but from the whole large body of students in all India's academic groves and haunts. That explains why, amid all the excitement and disturbance that India has seen of late, students everywhere have been quiet and restrained. As a general statement of what students have been doing that seems to have its weaknesses, but these may be passed over for the sake of the argument.

Students form a separate nation within, India larger than any other; larger than all others combined. Therefore, the letter gives us fifteen days' notice, Government will soon stand trembling in its trousers as hundreds and thousands of stalwart youths, compact of knowledge and resolution, march non-violently, non-violent swords in non-violent hands, to insist on autonomous republics for themselves at all seats of learning; for free cities constituted of themselves and governed by themselves for themselves. So one more "isthan" is on the horizon. Let there be free cities and autonomous republics for generous youth, owing no allegiance to the Government of the land. When a student ceases to be a student for this purpose the letter does not say.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, April 25. 1940)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

No

Silence

EDITORS have been asked to be kindly reticent while negotiations are going on between Congress and Muslim League leaders, and not cloud prospects by careless or excessive comment. This is not the highest form of compliment. Why should it be supposed that newspaper comment clouds whereas men in politics clarify ? Most men, of all communities, whatever their occupations and interests, are glad to see some approach of the parties whose aloofness has contributed greatly to the present stagnation in Indian politics. It is a resumption of activity from which large change may come. If Mr Gandhi and Mr Jinnah can reach an understanding about the great thing that divides Hindus generally from Muslims generally in their outlook at the present, the satisfaction will be great.

A settlement to satisfy Hindus, Muslims, Scheduled Castes, as well as Britain, will not be easy, though Britain's concern is that there shall be agreement, among Indians. What is under debate is the future of India, in relation to Britain and the Empire, and in her own internal structure. These are matters of grave importance, about which newspapers however pleasantly invited to silence, cannot long be reticent. Problems of this magnitude call for the greatest and responsible publicity. Nor does it help if anyone, newspaper or political leader, uses language that conceals, obscures, or minimizes what is at issue.

The word "settlement" itself looks pleasant and comfortable, but what is sought is a settlement about Pakistan, a word that many find provocative. We hear a great deal about Pakistan in principle. Even the Mahasabha. we suppose, are not worried about Pakistan as a principle. What they are sounding the trumpet and putting on their armour against is Pakistan as operation and fact. The Sikhs too appear to be in earnest against it. Is anything to be gained by silence about these verities ?

There is general hope that the negotiations now begun will lead to something good, above all to the end of the miserable stagnation in politics ; but settlement is identical with some arrangement about Pakistan, a word still undefined, and a large part of the people seem resolute against any arrangement of the kind. It does no good to soften language in the hope of mitigating feelings if this obscures realities. India cannot decide great matters in a twilight of thought and emotion.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 8. 1944)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Slaves,

Promises, Passions

By every sign & portent this would be India's

year of decision—a decision that would be

bitterly contested by all three partners to India's future: the British

Raj, 256 million Hindus, 92 million

Moslems.

Votes & Issues. As the year opened, Secretary

of State for India Lord Pethick-Lawrence

dutifully reiterated Britain's old promise: she would do all she could

to help India reach Dominion status. For

over three years, in one form or another, Britain had been offering just that—postwar independence

inside the Empire (i.e., Dominion status),

provided Indians could agree among themselves on what form of self-rule

they wanted. Hindus wanted a united,

free India; Moslems wanted a separate state for themselves (Pakistan) inside a free India. Both Hindus

and Moslems wanted the British to get out.

Last week the results of the first election in

eleven years for the Central Legislative Assembly were announced. Because of

franchise restrictions, which made them among the least representative of

India's elections, only about 600,000 voted. In this preliminary test, the predominantly Hindu Congress Party

won all the non-Moslem seats (56) and the

Moslem

League won all the Moslem seats (30); minor groups

won 16, with 39 members still to be

nominated.

Words & Moods. In the far more significant

provincial elections (30,000,000 voters), to

be held between January and April, the issue will be Pakistan—whether or

not to slice off the four predominantly

Moslem provinces in India's northwest corner, plus Bengal and Assam in the east, as a separate Moslem land.

The Moslem League's shrewd, elegant President

Mohamed AH Jinnah put it coolly: "India has never been a nation. It only looks that way

on a map. ... I want to eat the cow the Hindu

worships. When the Hindu shakes hands with me, he must go wash his

hands. Our religion is not all. Culture,

history, customs, all make Moslem India a different nation from Hindu India. The Moslem has nothing in common with

the Hindu except his slavery to the

British."

The Congress Party's grim, potent boss, Sardar

Vallabhbhai Patel, who hates Jinnah almost

as much as he does the British, was openly scornful of both. The Moslem

League, he said, had won electoral

advantages during the war by stooping to aid Britain. "Do I think the British are sincere," he asked, "in

their promise to leave India? They have been making promises ever since Queen Victoria's time,

and they have always broken them."

While Hindus and Moslems were snarling at each

other, Jawaharlal Nehru, ardent champion

of Indian independence, summed up for them and for the world India's New

Year's mood: "[We] will not

willingly submit to any empire or any domination, and will revolt against it. It will be a continuing revolt of

millions, with a passion behind it which even the atomic bomb will not suppress."

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Jan. 14, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

"If I

Were Dictator"

What should have been a week of triumph and hope

for India was a week of confusion,

riots, petty bickerings and incredible irrelevancies.

Things were so bad that Mohandas Gandhi devoted

his weekly day of silence, when he

usually gets a rest from the questions* that pour in from all over

India, to fuming and fretting over the

big question of Congress cooperation in an interim government.

Next day he successfully talked the Working

Committee of the Congress Party (of which he is the boss, though not a member)

into paying more attention to the crumbs than to the cake of freedom, which the

Raj was holding out.

At Gandhi's insistence, the Working Committee

refused to participate in the interim government of India unless the British

agreed to name at least one Moslem to the Congress Party group in the interim

government. Such a provision would

further infuriate the Moslem League's Mohamed Ali Jinnah. Gandhi was very tough in handling the

opposition to his policy. Objecting to newspaper stories about the

negotiations, he dropped his airof

outward benevolence, cried: "If I were appointed dictator for a day

in place of the Viceroy, I would stop all

newspapers—except, of course, Harijan" (Gandhi's mouthpiece).

Perhaps the

only man who could have stopped Gandhi was brilliant, unstable Jawaharlal Nehru, but he went off on a small and dizzy

tangent to his native Kashmir, where the

local maharaja, Sir Hari Singh, had arrested a popular leader, the sheik

Mohamed Abdullah. Sir Hari had Nehru arrested. In protest, thousands of Bombay

mill workers and Calcutta transport workers went on strike. Markets closed in

many cities, and in Madura five Indians were killed in riots.

The crowning irrelevancy came from the Government

of India itself, which presented charges to the United Nations against South

Africa's racial-discrimination laws covering Indian nationals. The Indian

evidence against South Africa was strong enough, but the plight of 250,000

Indians in South Africa was scarcely as important last week as the plight of

389,000,000 Indians in India, who, instead of standing happily on the threshold

of independence, were faced with famine and a growing chance of political

chaos.

*Typical questions: "Of what advantage is

decimal coinage?" "What should a sweeper do about the atom bomb?" "How can a

girl avoid being raped?"

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Jul. 1, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Long

Shadow (Jinnah)

India's festering sun beat down impartially on New and Old Delhi—on the precisely geometric, grandly drab preserves of the British Raj, on the noisy, squalid, sprawling native town. A sweat-soaked British wallah might change his shirt four times before settling down to an evening burra peg of bad Australian whiskey in the garden of the Cecil Hotel. Even the calloused, naked feet of shirtless Indians burned as they padded along the teeming Chandni Chauk. In the brassy glare, the flowering trees near the Viceroy's residence seemed to bear sparks rather than blossoms. The rind of an orange would shrivel the moment it was peeled from its fruit. Here & there an exhausted cow rested, sacred and undisturbed, in the traffic lanes of the boulevards.

Delhi in the spring heat of 1946 was not relaxed; it was taut with waiting, gravid with conflict and suspense. Two Socialist lawyers and a former Baptist lay preacher from Britain had sat for 25 days in the southeast wing of the viceregal palace, preparing to liquidate the richest portion of empire that history had ever seen—to end the British Raj, the grand and guilty edifice built and maintained by William Hawkins and Robert Clive, Warren Hastings and the Marquess Wellesley, the brawling editor James Silk Buckingham and the canny merchant Lord Inchcape, and by the great Viceroys, austere Curzon and gentle Halifax. The Raj was finished: scarcely a voice in Britain spoke against independence; scarcely an Indian wanted the British to stay; scarcely a leader in India questioned the sincerity of Britain's intention to get out. The only questions were "when?" and "how?"

Last week the three members of the British Cabinet Mission strove to force Indians to take the ultimate step—agreement on the constitution of an independent state. Much like a judge locking a hung jury in an uncomfortable room, Ministers Lord Pethick-Lawrence, A. V. Alexander and Sir Stafford Cripps prepared for a long Easter weekend in Kashmir's cool mountains with a message that when they returned "they hoped to find sufficient elements of agreement on which a settlement will be based."

Inside the cream stucco Imperial Hotel, beneath the propeller-blade fans, zealots and schemers argued, intrigued and speculated in more tongues than the Ganges has mouths. When they repeated to each other (as they often did) that now at last Britain's colonial policy had lumbered to the point where Whitehall really wanted to free India, hope revived. When they reflected (as they often did) that civil war had never been closer, despair reached .its depth. The issue seemed to turn on one man—Mohamed Ali Jinnah. Last week all India watched Jinnah's words and actions.

Man with an Angora Cap. While the Cabinet Mission still talked with India's leaders, a meeting was held in the courtyard of Anglo-Arabic College across Delhi from the Viceroy's palace. Green and white banners flaunted unacademic slogans: "Pakistan or die," "We are determined to fight." The speeches were equally inflammatory. Said Abdul Qaiyum Khan from the North-West Frontier Province: "I hope the Moslem nation will strike swiftly before [a Hindu] government can be set up in this country. . . . The Moslems will have no alternative but to take out their swords." Said Sirdar Shaukat Hyat Khan of the Punjab (which furnishes more than half the troops of the Indian regular army): "The Punjabi Moslems . . . will fight for you unto the death."

One of the wealthiest of Moslem leaders, Sir Firozkhan Noon, a Punjab landowner, did not hesitate to wave the Red flag; "If neither [the Hindus nor the British] give [Pakistan] to us . . . if our own course is to fight, and if in that fight we go down, the only course for Moslems is to look to Russia. ... I will be the first to lose every rupee I have in order that we may be free in this country." Five thousand Moslems cheered. Even the women in the purdah enclosure to the left of the platform could be heard-applauding behind their screen.

The presiding officer was neither shocked nor carried away by the incendiary speeches. Mohamed Ali Jinnah, clad in black angora cap, a long black sherwani (tunic), and tight-fitting black churidar on his wire-thin legs, smiled his ice-cold smile. He was at the peak of his power. He was the man who might say whether one-fifth of the world's people would be free. His 5 ft. 11 in. and 119 Ibs. stood between India and independence.

Man with a Monocle. After the meeting, Jinnah got out of his political costume as soon as possible, relaxed in his comfortable New Delhi home (he has a more palatial one on Bombay's Malabar Hill). He changed quickly to a tropical grey suit, blue & black striped tie, black & white sport shoes. Later, as he read to a reporter passages from one of his past speeches, Jinnah screwed a monocle into his right eye. He wears Moslem dress only because his enemies sneer that Jinnah, head of India's Moslem League, is lax in his religious observances. ("Jinnah does not have a beard; Jinnah does not go to the Mosque; Jinnah drinks whiskey!") With his perfect English, which he speaks better than his native Gujerati, his slick grey hair and graceful, precise gestures, he might be a European diplomat of the old school. How such a man at a fateful moment in history came to be the spokesman for millions of Moslem peasants, small shopkeepers and soldiers, is a story of love of country and lust for power, a story that twists and turns like a bullock track in the hills.

Jinnah was born on Christmas Day, 1876, the eldest son of Jinnah Poonja, a wealthy Karachi dealer in gum arabic and hides. The boy grew up in an atmosphere of wealth among a doting family. After going to school in Bombay and Karachi, young Jinnah, "a tall thin boy in a funny long yellow coat," as Poetess Sarojini Naidu described him, went to England. At the age of 16 he was admitted to Lincoln's Inn to read law. Soon after Jinnah returned to India, his father lost his money. Three hard, jobless years followed, until briefs and money started coming in.

Man of Unity. In 1940 Bombay Moslems elected him to the Supreme Legislative Council. Jinnah rose steadily in the councils of the nationalists and in the courtrooms of India. He revisited England and there, in 1913, enrolled in the Moslem League. "Typical of his sense of honor," wrote his rhapsodic biographer Naidu,* "he partook of it something like a sacrament . . . made his two sponsors take a solemn preliminary covenant that loyalty to the Moslem League . . . would in no way and at no time imply even the shadow of disloyalty to the larger national cause to which his life was dedicated."

During World War I Jinnah was a conspicuous worker for Moslem-Hindu unity, persuaded the Congress Party and Moslem League to hold joint sessions, used as his slogan "a free and federated India." In 1917 he could still attack the idea which later became his obsession. "This [fear of Hindu domination] is a bogey," he told League members, ". . . to scare you away from the cooperation with the Hindus which is essential for the establishment of self-government."

Man of Discord. The solemn dedication to the "larger national cause" began to waver after the war. The shrewd, suave Moslem saw a shrewd, complexly simple Hindu, Mohandas Gandhi, step into the leadership of the nationalist Congress

Party. When Gandhi began to turn the party, once the sounding board for polite talk about independence among a few cautious Indian leaders, into a powerful mass movement, Jinnah drifted out of the fold. Some Hindus think he lost his nationalist ardor when he lost his beautiful Parsi wife (he was 42, she 18, when they were married) after their only child, a daughter, was born. His wife had been a zealous worker for independence.

Since then he has shared his Malabar Hill and New Delhi homes with his sister, Fatima. He lives austerely, has no close friends. He disowned his daughter for marrying a rich Christian.

Even Poetess Naidu found little warmth in Jinnah: "Somewhat formal and fastidious and a little aloof and imperious of manner. . . . Tall and stately, but thin to the point of emaciation, languid and luxurious of habit, Jinnah's attenuated form is the deceptive sheath of a spirit of exceptional vitality and endurance."

Man of Threats. That vitality and cold intelligence were turned more & more to the Moslem cause during the late '30s. After the sweeping Congress Party victories in the 1936-37 provincial elections, Moslems charged that Hindus were trying to monopolize the government.

At a crucial meeting in March 1940 Jinnah first publicly plumped for Pakistan.* A hundred thousand followers thronged into the shade of a huge pandal (big tent) in Lahore, where the League was meeting, overflowed into the scorching heat outside, heard Jinnah proclaim over the loudspeaker: ". . . The only course open to us all is to allow the major nations [of India] to separate to their homelands." He warned that any democratic government in a unified India which gave Moslems a permanent minority "must lead to civil war and the raising of private armies." An enthusiastic woman follower tore off her veil, came from behind the purdah screen, mounted the speakers' platform. But Moslem revolutionary ardor was not ready to break with tradition; she was quietly escorted back to purdah by a uniformed guard.

When Gandhi led Congress into civil disobedience after the failure of the Cripps mission in 1942, Jinnah ordered his Moslems to take no part, promised a "state of benevolent neutrality" that would not hamper the British in fighting the Japanese. He boasted that if his followers joined Gandhi's pacifist program, the British would have 500 times more trouble "because we have 500 times more guts than the Hindus." He recalled past glories of the Mogul Emperor Baber ("The Tiger") and other Moslem warriors: "The Moslems have been slaves for only 200 years but the Hindus have been slaves for a thousand."

A historic meeting with Gandhi on Malabar Hill in 1944 ended in an impasse. Even Gandhi's healer, Dinshaw Mehta, who massaged Jinnah for two hours daily during the meetings, could not rub out the wrinkles of obstinacy that made the skinny Moslem uncompromisingly demand Pakistan, made the skinny Hindu as uncompromisingly demand a unified India, with the Pakistan issue postponed until after independence.

Man of Pomp. Today Jinnah revels in his one-man show. Nobody in all his Moslem League can be called a No. 2 man, or even No. 8. He delights in the princely processions staged by his followers when he tours the Moslem cities of northern India. His buglers herald his arrival at railway stations. Bands play God Save the King because "that's the only tune they know." Victory arches go up, rose petals flutter down from the rooftops, richly bedizened elephants, camels, mounted guards of honor accompany the Hollywood float in which Jinnah rides. Today Jinnah, and not the hated Hindu Gandhi, is prima donna on India's stage.

The gulf between Moslem and Hindu had always been real, but Jinnah dug it deeper. Last Christmas Day, Jinnah's 69th birthday, he summed up his demand for two nations. "I want to eat the cow the Hindu worships. . . . The Moslem has nothing in common with the Hindu except his slavery to the British."

Economic differences aggravate the irritation. Enterprising Hindus and Parsis almost monopolize banking, insurance, big business. Moslems, slower to welcome Western education, complain bitterly that Hindu factory owners rarely employ a Moslem clerk or foreman even when most workmen are Moslem. Moslems have a real fear that, in a unified India, Hindus would freeze them out of important posts in government and industry.

The British, in the years when they still hoped to hold India, gave the religious difference official standing by decreeing, in 1909, that Hindus and Moslems should vote separately. H. N. Brailsford, a sympathetic British student of India, has said: "We labeled them Hindus and Moslems till they forgot they were men." The British policy of "divide and rule" has been turned by Jinnah to the Pakistan demand "divide and quit."

The Poorest State. The British Raj had given India a unified defense and a unified region of internal free trade. Jinnah would destroy both. His Pakistan, in northwest and northeast India, would be an agricultural state, poor in resources and industry, unless, improbably, the Hindus agreed to turn Hindu Calcutta over to Pakistan. Between mighty Russia to the north and the main body of India to the south, Pakistan would dangle like two withered arms. Only half the population of the area claimed for Pakistan is Moslem. None could claim that to split India in twain would solve the minority problem—in Hindustan there would still be islands of Moslems, in Pakistan large Hindu minorities. Jinnah has not concealed that behind Pakistan lies the ancient Asiatic practice of taking hostages; a Hindu minority in Pakistan could, "by reprisals, be made to answer Tor persecution of Moslems in Hindu India.

To warnings that a separate Pakistan would be poor and backward, Jinnah answers: "Why are the Hindus worrying so much about us? Let us stew in our own juice if we are willing. . . . [The Hindus] would be getting rid of the poorest parts of India, so they ought to be glad. The economy would take care of itself in time."

The Plainest Answer. The Congress Party's position on Pakistan was just as firm as Jinnah's. The party's official head, goateed Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, a Moslem who looks like a caricature of a Kentucky colonel, paced up & down in his Delhi quarters last week, smoking a big cigar. "Eighty percent of the Indian people live in villages where Hindus and Moslems get along well together—the only trouble is among the twenty percent living in the cities. This is basically an economic conflict, not religious." Jawaharlal Nehru made the plainest answer: "Nothing on earth, including the United Nations, is going to bring about the Pakistan of Jinnah's conception." The Congress Party might compromise on some plan for a limited Pakistan within a federated India. Jinnah might change his mind—as he has so often before. But if neither gave way, the British Cabinet Mission would probably impose a constitution on India despite the threats of civil war. When a British official in Delhi last week said, "This is the most important British diplomatic effort of the century," he had in mind the danger that a failure to settle the Indian problem would keep the whole East in turmoil and disturb international relations throughout the world by presenting Rus sia with an opportunity to increase her influence among Asia's people.

Even if settlement of the constitutional issue resulted in an independent, unified India, the future was none too bright.

Famine was tightening its grip on the subcontinent. Sir A. Ramaswami Mudaliar warned of "ten million dead on the streets of India" unless he could buy four million tons of grain this year in the U.S.* Independence alone would not answer the food problem, which would recur until India had more irrigation, more fertilizer, better agricultural methods and more industry. Many Indian leaders looked to the U.S. for machinery and technical advice. The most practical immediate step would be a U.S. loan to Britain, which would permit London to pay off much of its wartime debt to India and to give India the dollars she needs for imports from the U.S.

Where Akbar Failed. If India, with its diverse tongues, its anachronistic princes and princelings, its millennium of dependence on the rule of outsiders, could become a nation in the Western sense, the achievement would be one of the greatest triumphs of history. In E. M. Forster's A Passage to India, a Moslem character, Dr. Aziz, recalled that the great Mogul Emperor Akbar had worked with tolerance and wisdom to unite India, had even attempted to devise a new unifying faith. But, says Dr. Aziz: "Nothing embraces the whole of India—nothing, nothing, and that was Akbar's mistake."

This people without a common denominator are at the same time the most bound and the most free in the world. They are bound by poverty, by caste, by religious practices that often descend to the crassest animism, by political ignorance and by disease. Yet they have been free enough to produce great contemporary leaders and thinkers. Nobody, not even the British Raj in the days of its strength, has regimented the Indians, who wear a thousand local costumes, speak 225 languages, and follow highly individual patterns of behavior. An Indian is free to sleep on the sidewalks of Madras when he feels tired, or to declare himself a saint and sit waiting for disciples by the burning ghats of Benares; or to send out a seven-year-old child with a dead baby dangling from its hand to beg in Calcutta's Howrah railroad station.

No one who looked at India's anarchic scene last week could believe that Jinnah had created all the obstacles to India's freedom, but in the present crisis he had come to symbolize them. The Indian sun cast Jinnah's long thin shadow not only across the negotiations in Delhi but over India's future.

* At 67 plump Madame Naidu is still a member of the Congress Party's Working Committee, is considered India's topmost orator. She paints her toenails bright red.

* Pakistan, a dream of Moslem students before it became a political issue, was originally concocted from P for Punjab, A for the Afghans of the North-West Frontier, K for Kashmir, S for Sind, "pure" in Tan from Urdu, with "stan" Baluchistan. means "Pak" also "Land of the means Pure." Last week the League convention defined it to embrace Punjab, Sind, Baluchistan, North-West Frontier Province (all in northwestern In dia), Assam and most of Bengal (in the north east). Jinnah has even advocated a thousand-mile corridor across Hindustan to connect the two parts.

* In 1943's Bengal famine 1.5 million starved.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Apr. 22, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Flight to

Nowhere?

In the four-engined York monoplane, London-bound,

the "No Smoking" sign stayed on for an hour out of Karachi. When it went out,

Mohamed Ali Jinnah, in a front-row seat,

chain-smoked State Express 555 cigarets, buried his hawk's head in a

book pointedly titled A Nation Betrayed.

Behind him sat Pandit Jawar-halal Nehru, chain-smoking Chesterfields, wearing

Western-style clothes for the first time in eight years. Between Karachi and

Malta, Nehru breezed through Rosamond Lehmann's The Ballad and the Source and

Sinclair Lewis' Cass Timberlane, chatted with his good friend, Sikh leader

Sardar Balder Singh. In the plane's third row sat Viscount Wavell, Viceroy of

India. For three years he had been

trying to bring Nehru and Jinnah into agreement, now, with the peace of India hanging by a thread, they were

a yard apart in space, politically as

remote as ever.

At Malta, where they had to wait for another

plane, the rival leaders spoke for the first

time. Their conversation, in toto:

Jinnah: "Well, what have you been doing all

day?"

Nehru: "Partly reading, partly sleeping,

partly walking."

Who Gets Pushed? At the London Airport, where they

were greeted by Britain's aging, able

Lord Pethick-Lawrence, local Indians were out before dawn in coal

trucks, bicycles and buses. A policeman

grumbled: "You can't tell by looking at these Indians who are the

VIPs and who are the riffraff. One day

you're arresting a fellow and the next he turns up as an important bloke. . . . You never can tell

who to push around."

Nehru moved about at receptions with high good

humor and grace. At India House, he shook

hands with the Dowager Marchioness of Willingdon, whose husband had

jailed him; at Buckingham Palace, he ate

from His Majesty's gold plate, a delightful change from the tin service he had known as a nine-year guest in

H. M.'s prisons. Jinnah was socially crusty,

giving the impression of a man deeply aggrieved. When the travelers got

down to cases, however, it was the

smiling Nehru who proved most stubborn.

The point at issue was one of those legal

technicalities on which the fate of whole

nations sometimes depends. The British Cabinet Mission had divided

India's provinces, for purposes of

writing the provincial constitutions, into three groups. In Group A, which comprised the bulk of British India, the

Hindus would have a huge majority. Group B was

the predominantly Moslem Northwest. The

trouble narrowed down to Group C in the East,

consisting of Bengal and Assam. Nehru said that the vote in the Assembly

should be cast by provinces, which would

let him take advantage of the 7-to-3 Hindu majority in Assam. Jinnah said that the vote should be cast for

Group C as a whole. In this way his 33to-27

majority in Bengal would wipe out the Hindu margin in Assam and give the

Moslems a 36-to-34 edge (in effect, a

limited Pakistan) in Group C. The British agreed with Jinnah.

On this interpretation of the rules, Nehru would

not play. Jinnah said that unless he got

his way, the 75 Moslem League seats would be vacant when the Constituent

Assembly met in New Delhi to draft free

India's constitution.

Silly? Finally Clement Attlee tired of this

variation of musical chairs, in which one

seat was always empty. He warned the Indians that if "a large

section of the Indian population"

(i.e., the 92,000,000 Moslems) were not represented in the framing of a constitution, His Majesty's Government would

not turn over power to a Congress Party

government. It looked like a win on points for Jinnah. Said Nehru:

"It was silly to expect to solve in

three days problems which have been under discussion for many months."

Off he flew to New Delhi, where he found Congress

Hindus in a belligerent mood:

fierce-eyed Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel thought Nehru had been

"tricked" into going to London.

Cried Patel: "So long as the Moslems insist on their demand of Pakistan,

there shall never be peace in India. We

will resist the sword with the sword."

The Assembly that was to make India a nation

quietly convened in New Delhi's Central

Assembly Library. Pictures of former British Viceroys had been removed

from their gilded frames. Special police

were standing by with tear gas.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Dec. 16, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Reprieve from

Disaster

Down a jungle walk on Bengal's marshy coast last

week, two Indian political leaders

stalked solemnly away from Mohandas K. Gandhi's tin-roofed hut, burned

out in recent communal rioting. They

were Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and President Acharya Kripalani of the All-India Congress Party. Hindu women

blew conch shells, and thousands of devotees

showered the two leaders with flowers.

Well might Nehru and Kripalani look solemn. As

India seemed to teeter on the brink of

bloodshed, they were returning to New Delhi, to face the Congress

organization's toughest problem: to

accept or reject the British version of how the Constituent Assembly

should be run (TIME, Dec. 16). With

Nehru and Kripalani went Gandhi's blessing and advice. They would

not say whether the Mahatma had recommended concessions that might win

Mohamed Ali Jinnah's Moslem League to Assembly participation.

Next day, Gandhi renewed his spiritual campaign

against India's bitter communal feuding.

At 7:35 on the morning of Jan. 2, clasping a long bamboo pole in his

right hand and flanked by four

companions, Gandhi set out on a walking tour of Bengal's Noakhali district. On his "last and

greatest" experiment, the Mahatma said he would visit 26 Moslem villages, would seek to rekindle the

lamp of "neigh-borliness" quenched in that area (and in much of India) by blood.

Few dared hope that Gandhi's saintly pilgrimage

would influence more than a handful of

Moslems. But few, doubted this week that it was his New Year's advice

which Nehru and Kripalani ex pressed in

a Congress resolution that gave a well-hedged "yes" to the British pro posal, and opened the door to

Jinnah for a face-saving entry into the

Assembly.

Third Alternative. The British Cabinet Mission had

divided India's eleven provinces into

three groups for drafting provincial constitutions, and had made it

clear last month that each group must

vote as a whole on each draft. Group A was incontestably Hindu; Group B lumped Moslem-dominated Punjab and Sind

together with the Congress-dominated North-West

Frontier; Group C paired Bengal and Assam, where 36 million Moslems live

with 34 million non-Moslems. Congress

held out for a prov-ince-by-province vote within each group, which would assure it of a dominant voice in eight

drafts instead of six. Mohamed Ali Jinnah

sat tight with the British; under the group-voting plan, he had a slight

edge over Congress in Groups B and C.

The apparent Hindu choices: acceptance, or an immediate showdown with the British and the Moslem

League.

The ameliorating resolution was in part political

doubletalk. It accepted the group voting

plan, but asserted: "In the event of any attempt at . . . compulsion, a

province or a part of a province has the

right to take such action necessary as to give effect to the wishes of the people concerned."

Since the British plan was only for

constitution-drafting, this represented little change except to give the

Congress Party a future out if some

Congress provinces or districts later proved recalcitrant.

Anti-British Revolution. Like most compromises,

the resolution satisfied no one

completely (it was passed 99-to-52—the narrowest victory the Congress

High Command has won in the working

committee). Least of all did it please Jai Prakash Narain, 44, head of the Congress Party Socialists, who favors an

anti-British revolution, has called Jinnah a

British stooge. Last week he told the students and faculty of the Hindu

University of Benares: "In the

coming fight, Congress will not have the same objects as in past struggles. Congress workers will not go to

jail. Instead, they will have strength enough

this time to do the arresting themselves. When the revolution starts,

our strategy will be to capture all

Government offices and institutions and establish a People's Raj. British governors and pro-British officials

should be jailed. . . ."

A year ago this speech would have landed Narain

himself in jail. Now the British are

powerless to stop his rabble-rousing without the consent of the Congress

Ministry of the United Provinces. The

very fact that Narain remains free to speak as he does underscores the fact that the British are virtually

throwing themselves out of India.

"Steel Frame." From New Delhi, TIME

Correspondent Robert Neville reported: "The British position in India is weakening so fast that

in a few months' time the British will be

unable to impose their will here a day longer, leaving Congress sitting

pretty. Eighty-five per cent of the

British personnel of the Indian Civil Service have indicated their intention of leaving soon, and 80% of

the British officers of the Indian Army are

leaving.

"In the press, both League and Congress are

very violent, and speeches of leaders on both

sides are continually inciting bloodshed. At last week's Hindu

Mahasabha* Session at Gorakhpur, the mention

of Nehru's name was greeted with shouts of 'Traitor!' At the conclusion of a violent speech, a member of

the audience climbed on the platform, cut his

hand, and offered blood then & there. The recent Sind election

campaign generally consisted of speeches

of vilification, one community v. another.

"In other words, there is little

give-&-take these days in Indian public life. Instead of one Government, there are two. The

Government's Moslem League members do not even answer the queries of Congress members, and refuse

cooperation and coordination. The Government

of India is simply running down. No decisions are being taken, no

policies are being formulated, all

actions are postponed. Unabashed communalism in the Government of India's secretariat has almost ruined that once

efficient civil service. Permanent secretaries

refusing to subscribe to the political and religious views of

communal-minded Cabinet ministers are

soon transferred or retired. The frank purpose of many Pakistan-minded Government servants is to undermine the

central administration.

"Topping this, there is also an elaborate spy

system throughout the secretariat, where

the Government servants of one department report for the heads of other

departments. There are Moslem League

cells throughout the secretariat, and often the League's paper Dawn reprints secret letters and memoranda

taken from Government files. The League's

avowed purpose, to sabotage the Interim Government, is being rapidly

achieved."

If Narain, Jinnah and their followers continued to

pour oil on the troubled flames, even Mohandas

K. Gandhi's genius for "neighborliness"—political and personal—might

not be enough.

* The militant, Hindu communal organization, which

considers the Congress Party too lenient

toward the Moslem League.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Jan. 13, 1947)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Anti-Vivisection

Hindu holy men were alarmed. Holy India was going

to be divided. Worse, the Indian

Government had taken steps to break down untouchability and other

extreme outgrowths of Hinduism. So, from

all over India, the holy men trudged to Delhi, set up camp along the bank of the Jumna River. There the sadhus

huddled around holy fires and chanted appeals

to the Universal Force "to save earth's children from

destruction." In groups they

picketed the Parliamentary Rotunda (where the Constituent Assembly was

meeting), Cabinet ministers' homes, the

Government Secretariat. They shouted slogans: "Absolute Good unto All," "Cow Slaughter Must Be

Banned," "Woe unto Evil."

They also cried the chief demand in their

five-point program for a revival of Hindu

orthodoxy: "Stop the vivisection of India."

Agreement to Disunite. Far away from the Jumna's

banks, in the quiet atmosphere of

London's No. 10 Downing St., a Briton who had striven desperately to

save Mother India from vivisection

reluctantly prepared the operating table. Rear Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, Viceroy of India, laid

before the full British Cabinet his plan for

handing over British power to Indians. The knotty question was, what

power to which Indians? Every Indian

leader except Mohandas Gandhi had agreed that they could not unite, but could not agree how to disunite.

"Dickie" Mountbatten was for a quick

showdown. India's leaders would meet in Delhi June 2. Mountbatten would give them one more

chance to accept or reject, once & for all,

Britain's 1946 plan for India—a loose federation of states. If they

rejected it (and Mohamed Ali Jinnah, the

Moslem leader, almost certainly would), then Mountbatten would suggest an alternative. Under it, each

province could decide for itself whether 1) to

join Hindustan, 2) to join Pakistan, 3) to set itself up as an independent

nation.

In both the Punjab and Bengal, provincial

assemblymen from each side of tentative

dividing lines would meet separately to pick an electoral college which

would register its choice. Punjab Sikhs would be split if the Punjab split. In

the North-West Frontier Province, where the Congress Party controls the

Government but 93% of the population is Moslem, a popular referendum would be

held. The likely choice: Pakistan. Bengal, with its rich industrial nucleus of Calcutta, might

choose to stand apart as a separate nation,

part Moslem, part Hindu.

Who Gets the Army? Not one British Cabinet member

liked this melancholy geometry. Even if

it had to be accepted, the British hoped there would be one strong mold

to bind the pieces—the Indian Army (present

strength: 400,000, with 9,000 Indian officers, 4,000 British officers). The Hindus (56%), Moslems

(34%), Sikhs and Christians in its ranks

have worked together with minimum friction. In recent communal riots

local police proved ineffective, while

the Army's Hindu and Moslem troops obeyed orders, often succeeded in checking disturbances. But a purely Moslem

army could not be expected to protect Hindu

minorities in Pakistan, nor a Hindu army to protect Moslems in

Hindustan. That did not bother Jinnah.

Last week he pontificated: "All the armed forces must be divided. . .

."

Typically, Jinnah wanted to eat the cake of Moslem

separatism, and have the cake of Hindu

manpower. Pakistan, said his mouthpiece Dawn, should have all troops now

stationed in the northern and eastern

commands (most of the troops, including Hindus and Sikhs, are in those areas). Even a division along communal

lines, which Jinnah might consistently have

asked for, would wreck the Army at a crucial time when Britons are

pulling out, leaving many half-trained

reserves in lower echelons, a drastic shortage of officers at the top.

If the Indian Army could be broken into two

efficient parts, the main mission of each

would be to watch the other. This cancellation would leave India defenseless,

invite the evolution of Pakistan and

Hindustan into Stalinistan.

A Martyr's Grave. By week's end, the 600 sadhus

who had gathered on the Jumna's banks had

a martyr,* if not a program for India. Swami Krishnanandji, like many

another holy picketer, had been taken to

jail. The police took away his trishool (5-ft. wooden staff with three points, known as the "stick

of righteousness"), without which no sadhu can take food. So Krishnanandji went on a hunger

strike. The police released him, but too

late. He trudged wearily back to the sadhu camp. The next day, while a

score of fellow ascetics chanted prayers

and slogans ("Victory unto the Lord who alone destroys all Evil"), Krishnanandji quietly died. His

friends dug a grave, 6 ft. deep, in the sandy

banks of the Jumna. There, in a sitting position, banked on all sides

with cakes of salt, Krishnanandji was

buried.

Thereafter the police were reluctant to jail the

holy men. Instead they piled demonstrators

into a van (although many holy men had vowed always to walk and never to ride on wheels), drove them 20 or 30 miles

out into the country. Some wondered if even a

Jinnah would show the single-minded stubbornness of the sadhus; many of

them plodded back to Delhi through the

blistering heat (113°), chanting "Good understanding among all living beings."

*They also had an unofficial pressagent. No sadhu,

Nandlal Sharma, like pressagents the

world over, stated his case in soaring sentences. "I am proud that

I can trace my dynasty back a thousand

years," he said, "even back to the Creator. That is because of

the chastity of our women. The ground

has always been pure and the seed has been good. We believe Hinduism has existed for so many

thousands of years because of the purity of our

blood. The world today is threatened with imminent destruction, mainly

because of the unchastity of women all

over the world. . . ."

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Jun. 2, 1947)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

06 April 1947 - Tarakeshwar Conference of Provincial Hindu

Mahasabha

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Twilight

of Bengal

WHERE all are for the party and none is for the State, and parties grow increasingly communal, an independent outlook tends to be regarded as pusillanimous or, worse, is supposed to arise from some hidden, disreputable motive. To be in the fashion oil must seemingly be poured not on troubled waters, but on the flames. We have not lately written much on the communal-political affairs of Bengal, because we felt it would do little good. Goondas may be illiterate, politicians purblind.

The origin if not the causes of the disorder in Calcutta are obscure and it is hard to find a remedy. This does not daunt our contemporaries who have many suggestions to offer—though that which is most popular, to overthrow the Government, and paralyse the police seems with all respect not good.

Extremists -have the upper hand. An evident exception nowadays is the Chief Minister, Mr H. S. Suhrawardy, whose reputation has risen since last year, and who is unpopular despite all his moderation, perhaps because of it. Politically-minded Hindus, though they could probably even now get the seats in the Cabinet for the asking, have become so embittered that nothing less than division of the Province will content them.

During ten weeks or so, the movement for re-partition of Bengal has grown from a cloud no bigger than a man's hand into a storm which blows over all the Province and outside the borders, though the centre remains Calcutta. Postered initially by the Hindu Mahasabha, which has not lost its influence with its seats in the legislatures, it received strong impetus from the declaration of Feb. 20 and the Congress Working Committee's resolution of March 8, on partition of the Punjab. It has not been taken over by the Provincial Congress Committee, which demands regional Ministries, and has backed this up by a powerful assault on the financial policy of the League Cabinet.

The Cabinet, however, seems likely to remain passive before an attack which it claims with some truth is communally inspired. Seeing that the plan for an interim division is unlikely to be realized. Dr Shyama Prasad Mookherjee, the Mahasabha leader, has now gone further, and suggests the alternative of administration under Section 93.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, April 24, 1947)

.

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

11 April 1947 - Petition for the Partition of Bengal in

Constituent Assembly

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

27 April 1947 - Suhrawardy Bose Plan for an independent

undivided Bengal

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

April 1947 –

Governor Burrows’ Plan for a Free City of Calcutta

[31630historiceventspartitiont.html#freecity]

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

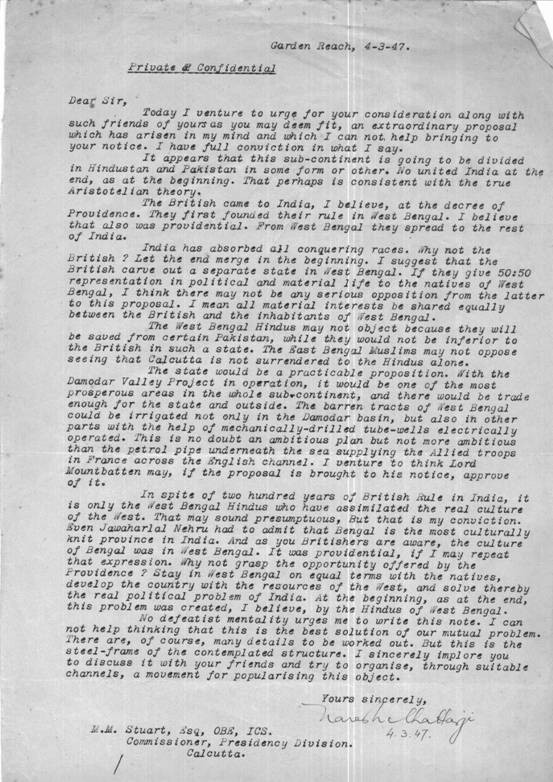

Plan for a British/Hindu West Bengal

[??] Chattarji, Calcutta

(source: personal scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005

/ Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

03

June 1947 – Mountbatten’s announcement of Bengal partition

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Centrifugal

Politics

Perhaps, after all, there would be no independent

India; indeed, there might be no India.

By last week nine months of slaughter, pillage,

and arson had killed nearly 15,000* Indians

(according to low Government estimates), had all but persuaded Britons and Congress leaders that Moslems and Hindus

could not cooperate in a unified nation. Almost

everybody but Gandhi now accepts the principle of Pakistan (a separate

Moslem state or states). Even Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru has said:

"The Moslem League can have Pakistan if

they wish to have it." But he served notice that if India was going

to split along communal lines, Congress

would not let Jinnah have non-Moslem territories which he claims. "If parts of Punjab and Bengal

want to separate no one can compel them the other way."

Even the Moslem League's cold, uncompromising

Mohamed Ali Jinnah was getting cold feet.

He said: "The question of the partitioning of Bengal and Punjab is

raised ... to unnerve the Moslems by . .

. emphasizing that the Moslems will get truncated or mutilated in a moth-eaten Pakistan. . . . It's a mistake to

compare the basic principle of demand for

Pakistan [with] cutting up provinces throughout India into

fragmentation."

Jinnah could not stop the centrifugal spin even if

he wanted to. His Moslem followers had

been whipped into an irreversible crusade for Pakistan. Their motives

ran all the way from deep religious

fervor to that of one Moslem politician who said: "In Hindustan I would be nothing, but in Pakistan I could be

Secretary of State for Air."

Two men worked for unity. The Viceroy, Lord

Mountbatten (who had just returned from a

peace tour in the turbulent North-West Frontier Province), sent two

emissaries to London. Their report

stressed the danger of dissolution, but contained no suggestion that the British remain in India beyond next year's

deadline.

Gandhi, dressed in a newly starched khadi loin

cloth, with a white cotton shawl over his

bare shoulders, drove in a new, green Studebaker to Jinnah's stucco

house. Acting the part of Qaed-e-Azam

(Head of the Nation), Jinnah sent his secretary to greet Gandhi at his car, waited inside the house for his

first private meeting with the Hindu leader in

three years.

When Gandhi left, two hours and 45 minutes later,

Pakistan was closer than ever. Jinnah

had not budged an inch. Neither had Gandhi. Said he: "I can never

be a party to the division of India. I

cannot bear the thought of it."

Perhaps the most discouraging sign in India was

the fact that factional intolerance had

invaded Gandhi's own prayer meetings. Some of his followers no longer

allowed him to read the Koran along with

the Hindu Bhagavadgita.

He might find a bitter prophecy in a poem by

Mohamed Iqbal:

Why can I not manage this earthly business?

Why is the religious sage a fool on earth?

* Almost double the total of Americans killed in

the War of Independence, the War of 1812

and the Mexican War.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

May. 19, 1947)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

June

Hopes

OUR views about Pakistan are known. Consistently, for years, we have deplored the project. Until the last moment, which was this week, we argued fervently against it. We think it retrograde. Profounder impoverishment and weakness in this populous sub-continent will we fear be its consequences, initially at least. It affronts world-tendencies; everywhere nowadays—except here—humanity is a disintegrator. It undoes the grandest achievement of Britain's 200 years Raj; the establishment of cohesion from diversity.

Nevertheless, by Tuesday's pivotal announcement in Delhi and London, creation of Pakistan this year becomes practically certain. That fact must now be fully accepted, by men of goodwill and the best be made of it. However sharp their regrets, the fair-minded must recognize that the considerations and actualities which led to this dismal happening have weight. What optimists may now look forward to is that. Having agreed to part, the two fragments of hitherto unified India may before very long spontaneously find their way back to some amicable re-combination for the good of the common people in each.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, June 6. 1947)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

20

June 1947 - Bengal Assembly votes for Bengal to join Pakistan

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Partition

VOTING in Bengal has gone as expected—for Pakistan and for partition. There was no practical alternative. Speculation about, what would have happened had Muslims preferred to forgo division of the country, so as to keep the Province united, or Hindus not to divide the Province so that India would not be divided, is futile. That some voted yesterday against their better judgement is clear. That others will live to regret their voice is possible. But it would be vain to spend time in regret over what is done, or hope that it will be undone.

LIKE Bengal, the Punjab has chosen Pakistan and partition, but in circumstances different and less easy. Though in Calcutta communal outrages continue and have slightly worsened again lately, so that the strictest control is still needed, the general disposition in the Province, after as before the vote, evidently is to accept the inevitable calmly and to strive to part as friends, In burning Lahore such an attitude is hardly possible. Now that the decision has been taken, perhaps communal passion, which has dominated events in the Punjab since HMG's declaration of February, will diminish. But we see little positive basis for expecting this, and the activities some weeks hence of the Boundary Commissions, in the Punjab even more than in Bengal may again try tempers sorely.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, June 24, 1947)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

End

of Forever

On a turf-covered plain near Delhi, a splendid assemblage gathered Jan. 1, 1877. The High Officers and Ruling Chiefs of India took their seats behind a gilt railing in an amphitheater of blue, white, gold and red, to hear Queen Victoria proclaimed first Empress of India. They rose to their feet as a flourish of trumpets announced the arrival, across 800 feet of red carpet, of His Excellency the Viceroy, Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, Second Baron Lytton. The proclamation was read, the Royal Standard was hoisted, and artillery fired a grand salute of 101 salvos. Mixed bands played God Save the Queen, then trumpeted the blaring march from Tannhduser. Richly caparisoned elephants trumpeted too, and rushed wildly about with trunks erect when they heard the roll of musketry.

His Highness the Maharaja Sindia was first to congratulate (in absentia) the new Empress: "Shah-en-Shah Padishah [Queen of Queens], May God bless you. The Princes of India bless you and pray that your sovereignty and power may remain steadfast forever."

Bleats of a Goat. "Forever" might have been a longer time if it had not been for a scrawny, timid schoolboy then in the northwest India town of Porbandar on the Arabian Sea, 700 miles away. Mohandas Kamarchand Gandhi was eight years old at the time of the Great Durbar at Delhi. He was already sensitive about his British rulers. His schoolmates used to recite a bit of doggerel:

Behold the mighty Englishman! He rules the Indian small, Because being a meat eater He is five cubits* tall.

Although his parents were pious Vaishnavas (a Hindu sect which strictly abstains from meat eating), Gandhi was goaded a few years later into sampling goat meat to emulate the British. "Afterwards," he reported, "I passed a very bad night. . . . Every time I dropped off to sleep, it would seem as though a live goat were bleating inside me; and I would jump up full of remorse."

Gandhi's frail body never grew beyond no pounds, but the youthful conscience matured into a towering spirit that laid the meat eaters low, five cubits or not. Winston Churchill had once called Gandhi "a half-naked, seditious fakir. . . . These Indian politicians," he said in 1930, "will never get dominion status in their lifetimes." But 70 years after the Great Durbar both Gandhi and Churchill were still alive, and freedom was only 50 days away.

Froth of a Flood. Last week in New Delhi, Queen-Empress Victoria's great-grandson, Rear Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, Viceroy of India, was working hard to get out of India as fast as he could. To Hindu and Moslem politicos responsible for setting up two new dominions in India before mid-August he sent memos reminding them "only 62 more days," "only 55 more days." The British did not rely on Hindu and Moslem leaders' continuing to work together. The British wanted to clear out before India blew up in their faces.

On the outskirts of New Delhi, in the dingy, dungy Bhangi (untouchable) Colony, Gandhi was not jubilant, although the British were leaving at last. To him, the violence and disunity of India were a personal affront. To Gandhi, ahimsa (nonviolence) is the first principle of life, and satyagraha (soul force, or conquering through love), the only proper way of life. In the whitewashed, DDT-ed compound which serves him as headquarters, Gandhi licked his soul wounds: "I feel [India's violence] is just an indication," he told his followers, "that as we are throwing off the foreign yoke, all the dirt and froth is coming to the surface. When the Ganges is in flood the water is turbid."

Ironically, Gandhi himself, who has spent a lifetime trying to direct the waters into disciplined channels, had helped to roil his people into turbulence. What he had called the "dumb, toiling, semi-starving millions," who revered (and sometimes worshiped) Gandhi, could understand him when he cried for their freedom; they could not always understand him when he told them they must not use violence to win that freedom. "To inculcate perfect discipline and nonviolence among 400,000,000," he once said, "is no joke."

A Young Bird Knows. Gandhi seriously began his own self-discipline when he went to South Africa as a London-educated vakil (barrister) at the age of 23. There he first felt the full weight of the white man's color bar. More & more he neglected a lucrative law practice to lead his fellow Indians in a fight against local anti-Indian laws.

A British friend lent him Count Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God is Within You. The Russian Christian's doctrine of nonviolent resistance to unjust rule gripped the Hindu lawyer's mind. "Young birds," wrote Tolstoy, ". . . know very well when there is no longer room for them in the eggs. ... A man who has outgrown the State can no more be coerced into submission to its laws than can the fledgling be made to re-enter its shell."

Gandhi broke his shell. He decided manual labor was essential to the good life; he still thinks Indians will find peace only through making their own clothes on the charka (spinning wheel). So he gave up a legal practice bringing in about £5,000 a year, moved to a farm settlement where his helpers worked the ground, and began to get out a newspaper, Indian Opinion.

Gandhi mobilized local Indians for his first civil disobedience campaign. They won repeal of some anti-Indian laws from an obstinate South African Government. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to Bombay, the hero of India.

Colossal Experiment. The first year after his return Gandhi toured much of India. The gentle ascetic in loincloth, walking among the villages, won the hearts of millions of Indians. "Gandhi says" became synonymous with "The truth is," for many a peasant and villager. When simple peasants crowded round to see him (many tried to kiss his feet), Gandhi tried to stop "the craze for darshan" (beholding a god).

The Mahatma (Great Soul), as he came to be called, insisted he was a religious leader, not a politician. "If I seem to take part in politics," he said, "it is only because politics today encircle us like the coils of a snake from which one cannot get out no matter how one tries. I wish to wrestle with the snake. ... I am trying to introduce religion into politics."

Applied to India, that meant to Gandhi that people could not be pure in thought, word and deed unless they were their own masters. So he began to work for Indian independence. He found India's "struggle" for independence in the hands of a few well-educated Indians. The Indian National Congress,* was a polite debating society, pledged to win dominion status for India by "legitimate" means. Gandhi converted it into a mass movement. Indian peasants did not worry about independence until Gandhi told them to.

British repressive measures after World War I convinced Gandhi that the British would never willingly give India dominion status. So he organized satyagraha. This first campaign came near to unseating the British Raj. "Gandhi's was the most colossal experiment in world history, and it came within an inch of succeeding," admitted the British governor of Bombay.

Himalayan Miscalculation. But passive resistance always erupted into violence. When he saw the bloodshed that followed his call for resistance, Gandhi was overwhelmed with remorse. He called off his campaign in 1922, admitted himself guilty of a "Himalayan miscalculation." His followers were not yet self-disciplined enough to be trusted with satyagraha. To become a "fitter instrument" to lead, Gandhi imposed on himself a five-day fast.

The pattern repeated itself in later years. The ways of passive action—the sari-clad women lying on railway tracks, the distilling of illicit salt from the sea, the boycotting of British shops, the strikes, the banner-waving processions—would lead to shots in the streets, to burning and looting. Gandhi always punished himself for his followers' transgressions by imposing a fast on himself.

With each fast, each boycott, and each imprisonment (by a British Raj which feared to leave him free, feared even more that he would die on their hands and enrage all India), Gandhi came closer to his goal of a free India. With the same weapons he got in some blows at his favorite social evils—untouchability, liquor, landlord extortions, child marriages, the low status of women.

But as he wrestled, India and Indian politics changed along the road. The Indian National Congress, which claimed to represent Indians of every religious community, finally had to admit that Mohamed Ali Jinnah spoke for the Moslems. Left-wing groups left the Congress, Communists led by Puran Chandra Joshi threatened the placid order of the agricultural, home-industrial India which Gandhi strove for. The Congress leadership (since 1941 Gandhi has ruled only from the sidelines) passed more & more to a group of well-to-do conservatives bossed by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

The only outstanding exception was socialistic Jawaharlal Nehru. Indian independence was certain to be followed by a struggle for economic power. For all these bewildering problems Gandhi had an answer: hurt no living thing; live simply, peacefully, purely. But fewer & fewer listened to that part of his advice. Just as Gandhi had outgrown the shell of the British Raj, so Indian nationalism, Hindu and Moslem, showed signs of outgrowing Gandhi's teachings.

Horse Trading. The India of New Delhi politicians was little concerned with soul force. Old (70), rabble-rousing Mohamed Ali Jinnah, head of the Moslem League, was greeted by followers with shouts of "Shah-en-Shah Zindabad" (Long live the King of Kings). His birthplace, Karachi, would probably be capital of the new Pakistan, possibly be renamed Jinnahabad.

Jinnah was already using his new power to disrupt India further. In the face of Jawaharlal Nehru's blunt warning to the Indian princes ("We will not recognize the independence of any state in India"), Jinnah began courting them. Most princes had already decided to join Hindu India (see map), but the Nizam of Hyderabad (a Moslem) and Maharaja of Travancore (a Hindu) had each said he would go it alone. Jinnah dangled alliance-bait before them: "If states wish to remain independent ... we shall be glad to discuss with them and come to a settlement." Big Kashmir, still on the fence, was ruled by a Hindu, but its 76% Moslem population would probably bring it into Pakistan sooner or later.

Last week Harry St. John B. Philby, Briton-turned-Moslem, familiar intriguer in the Arab world and intimate of Saudi Arabia's King Ibn Saud, arrived in India "to buy tents." He went into a huddle with Moslem Leaguers and Hyderabad officials. Delhi was sure Jinnah was angling for the support of Moslem states in the Middle East.

His Pakistan would be strong agriculturally (with a wheat surplus in the rich Punjab, 85% of the world's jute an eastern Bengal), but weak industrially.

Pakistan would begin its career with no cotton mills, jute mills, iron or steel works,† copper or iron mines. Jinnah hoped to compensate for this weakness with foreign support, might keep Pakistan a British dominion even if Hindu India declared complete independence.

What Will Happen? But these maneuverings were remote from the India of mud and dung and (endless toil, which wondered in bewilderment what was happening to it. The little man in India had never asked for Pakistan or Hindustan or even for independence, except when his leaders told him. He was scarcely aware who ruled him. Recently a tattered Hindu peasant helped to repair a blowout on a car in the Punjab. Asked what he thought of the Government in New Delhi (now a temporary, joint Hindu-Moslem Cabinet, operating under viceregal veto), he replied, "I never heard of it."

If the symbol of unity at New Delhi was remote, the communal hatred that had forced the partition now faced was real enough. On both sides of the new dividing line, between Pakistan and Hindu India, minority groups wondered what to do. A Moslem tonga (two-wheeled carriage) driver, who had lived 20 years in Delhi, thought of moving to the Punjab. "I will wait and see what happens," he said. "If there is any trouble, I will send for my mother, my sister and my two buffalo, on my farm in the United Provinces." But it would cost him $50 to move to the Punjab—and the meager amount he collects in fares barely pays for food on the black market. Besides, he was still paying off a $200 debt incurred when he had tried vainly to save the life of a typhoid-stricken son.