The Great Calcutta Killings

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

● Sitemap ●

Reference ●

Last

updated: 19-May-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

Few

events of the 1940s are still as contested as the large scale communal riots in

August 1946. What do people remember of it? What was reported at the time?

Contradictions, and contested accounts are not unusual.

The

human tragedy of it all is undeniable though as is the fact that Calcutta and

even India as a whole was never the same again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Earlier Communal Riots

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about

1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

Jinnah Split

[…]

Socially,

Indian Moslems are a solid, self-conscious minority group (just less than one-fourth of India's population) ; Hindus

are a loosely-bound, sect-split, caste-stratified

majority (three-fourths).

Hindus are the

wealthier group. In general, Hindus are landowners, capitalists, shopkeepers, professionals, employers ;

Moslems are peasants, artisans, laborers.

In Bengal, where Hindus are only 43% of the population,

they pay 85% of the taxes.

One of the

main reasons for this difference is that usury, which accounts for far

more profit in India than trade, is

forbidden to Moslems by religious law.

[…]

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Dec. 4, 1939)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

A religious massacre was the

last thing we were prepared for

Independence

did not come to South Asia as a single, identifiable event in 1947, though that

is way most South Asians like to remember it. The slow, painful process of

dismantling British India began with the great Calcutta riots and ended with

the genocide in Punjab.

I was nine in 1946 and relatively new to Calcutta. Even at that age I could sense that the people around me had had enough of ‘shock’ and trauma. First, there had been the fear of Japanese bombing in the last days of the war, which had taken my mother, my younger brother and myself to a quieter city in the nearby state of Bihar, while my father had stayed back to work in Calcutta. The bombing was nothing to write home about, but it created tremendous panic all around and there was an exodus from Calcutta. Now we were back at the city, the war was over, and freedom was round the corner. But for a small outbreak of plague in 1946, Calcutta was limping back to normal.

Then there was the famine of 1942, precipitated by British wartime policies. Its memory was still fresh and Calcutta wore the scars of it. People no longer died of hunger in public view, but begging and fighting for food with street dogs near garbage bins was not uncommon. The memory of thousands of people slowly dying of hunger, without any resistance or violence, often in front of shops full of edibles, was still fresh in the minds of the Calcuttans. Most victims were peasants, many of them Muslims. They died without ransacking a single grocery, restaurant or sweetmeat shop. Whoever thought they would fight like tigers when it came to religious nationalism? A religious massacre was the last thing we were prepared for.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 1-2 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

Clashes before the killings

Clashes and riots had been know to take place when someone, deliberately or otherwise, squirted dye over a Muhammadan.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Titaghur, Holi 1944

(source:page 114 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

they were caught up in a

skirmish

He had two weeks at home before going back to Sandwich and

prepared to go the Far East. He didn’t know what he was going to be doing

there. Rumour had it was that they were going to build another Mulberry Harbour

but that was all speculation. The same unit was soon shipped to Bombay and then

went on to Calcutta. At Howrah Bridge they were caught up in a skirmish

between the Muslims on one side of the river, and Hindus on the other. He thinks

it was Ramadan. He wondered why they had been asked to try and keep them apart,

when both sides had guns! Bullets were flying so quickly that the British

soldiers could all have been massacred easily (there were only about 20

soldiers he thinks). And eventually the CO agreed with him and withdrew his

men. Apparently the skirmish was almost an annual event. A bit like the Orange

parade troubles. It happened when a Muslim festival was a bit too up-close for

the other side to tolerate.

Edward Ernest Joseph Fairhall , Royal

Engineers, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A4027943 From Balderton to Scotland, France and the Far East at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

"British pigs" go

home

Beginning to catch us up was the political undercurrent, the

unrest, Mr. Gandhi's Congress Party with Pandit Nehru at the helm were making

themselves heard and no more so than in Calcutta. "Gandhi Wallahs",

we called them, dressed in pure white dhoti clothing with hats to match were

squaring up to Mr. Jinnah's Muslim League Party. There were riots in the major

cities of India and we the Brits were caught up in the middle of it all.

"British pigs" go home they were saying and we were bewildered. We

had just prevented the Japs from the big take over of their country. Mind you,

we were too young at the time to worry too much about any Indian political

intrigue. We were more concerned about getting home, though the prospect of

that happening now, was remote.

Cliford Wood, Royal

Air Force wireless operator,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4254103 AN RAF WIRELESS OPERATOR ON THE BURMA FRONT (Part 3 of 3) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

‘I had never seen such

devastation’

[Nikhil Chakravartty had given up his studies to turn to a new career in journalism and by accident he walked into a Muslim political meeting. It was only the presence of mind of some Muslim journalists which saved his life - he was quickly ushered out and allowed to make good his escape to the safety of the Indian Communist Party headquarters where he was marooned for three days.]

I had never seen such devastation. Without a war hundreds of people were lying dead on the roadside - and still the fires burned all over the place. Many shops were being looted and many houses were burned down. On the third day I came back home where I found to my horror an old Muslim washerman being beaten up — civilised people who knew him were doing it.

Nikhil Chakravartty,

Journalist, Calcutta, November 1945

(source: page 135 of Trevor Royle: “The Last

Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

Muslim agitation

In 1946, the news came out that India would get her freedom the following year. Mr Jinnah had earlier formed the Muslim League and much shouting was going on from the Muslims. Slogans of all kinds were invented, but I did not, at the time, understand Mr Jinnah's object in detail. The general impression was: that all the noise was based on the idea that the Muslims should get equal representation in the new independent Indian Government.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, Calcutta 1946

(source: page 211 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

Kanme bidi, muhme pan, Ladke

lenge Pakistan

As

the tough negotiations for transfer of power began to heat up and communalise

the political atmosphere, in front of our eyes the slum dwellers turned into

active supporters of the Muslim League. They began to fly the green flag of the

party and, sometimes, take out small processions accompanied by much frenzied

drum beating. Many of the enthusiasts were middle-aged and looked very poor and

innocuous in their tattered clothes, even while shouting aggressive, martial

slogans. Their newfound politics did not change our distant but friendly social

equation with them. We, the children, were not afraid of them, and when we

teased them, they smiled. They would passionately shout their slogans and we the

kids would reply in our tinny voices: Kanme bidi, muhme pan, Ladke lenge

Pakistan. In any case, their fierce slogans seemed totally incongruous with

their betel nut chewing, easy style.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 2 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 August 1946 - Day of

Direct Action

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about

1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

'You will see the meaning

when the day comes.'

At a meeting in the Assembly, Mr Jinnah announced that 16th

August 1946, should be a 'Direct Action Day' for the Muslim League. When asked

what he meant by 'Direct Action Day,' his reply was short and sweet: 'You will

see the meaning when the day comes.' Nothing more seemed to have been asked; no

kind of preventive action against any disturbance was taken.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, Calcutta summer 1946

(source: page 211 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

The way to the Day of Direct

action

The unequivocal acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan by the Congress Working Committee led to an immediate response from the Viceroy. On 12 August, Jawaharlal was invited by him to form an interim Government at the Centre in the following terms:

His Excellency the Viceroy, with the approval of His Majesty's

Government has invited the President of the Congress to make

proposals for the immediate formation of an interim Government

and the President of the Congress has accepted the invitation.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru will shortly visit New Delhi to discuss this

proposal with His Excellency the Viceroy.

Mr Jinnah issued a statement the same day on which he said that 'the latest resolution of the Congress Working Committee passed at Wardha on 10 August does not carry us anywhere because it is only a repetition of the Congress stand taken by them from the very beginning, only put in a different phraseology'. He rejected Jawaharlal's invitation to cooperate in the formation of an interim Government. Later, on 15 August, Jawaharlal met Mr Jinnah at his house. Nothing however came out of their discussion and the situation rapidly deteriorated.

When the League Council met at the end of July and decided to resort to direct action, it also authorised Mr Jinnah to take any action he liked in pursuance of the programme. Mr Jinnah declared 16 August the Direct Action Day, but he did not make it clear what the programme would be. It was generally thought that there would be another meeting of the Muslim League Council to work out the details but this did not take place. On the other hand, I noticed in Calcutta that a strange situation was developing. In the past, political parties had observed special days by organising hartals, taking out processions and holding meetings. The League's Direct Action Day seemed to be of a different type. In Calcutta, I found a general feeling that on 16 August, the Muslim League would attack Congressmen and loot Congress property. Further panic was created when the Bengal Government decided to declare 16 August a public holiday. The Congress Party in the Bengal Assembly protested against this decision and when this proved ineffective, walked out in protest against the Government's policy in giving effect to a party decision through the use of Government machinery. There was a general sense of anxiety in Calcutta which was heightened by the fact that the Government was under the control of the Muslim league and Mr. H.S.Suhrawardy was the Chief Minister.

Maulana Azad, president of

Indian National Congress. Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 168-69 Maulana

Abdul Kalam Azad: “India Wins Freedom” London: Orient Longman, 1988.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Orient Longman 1988)

Announcement of

direct action day

The overt act that split India began in the streets of

Calcutta. But the decision was made in Bombay. It was a one-man decision, and

the man who made it was cool, calculating, unreligious. This determination to establish

a separate Islamic state came not—as one might have expected—from some Muslim

divine in archaic robes and flowing heard, but from a thoroughly Westernized,

English-educated attorney-at-law with a clean-shaven face and razor-sharp mind.

Mahomed Ali Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League and architect of Pakistan, had

for many years worked at the side of Nehru and Gandhi for a free, united India,

until in the evening of his life he broke sharply with his past to achieve a

separate Pakistan.

Jinnah lived to see himself ruler of the world's largest

Islamic nation before he died in September 1948, at the age of seventy-two, but

I think of him as reaching his pinnacle of power two years before his death,

when freedom-with-unity appeared on the verge of becoming a reality and he took

the momentous steps that crushed all hopes for a united India.

Jinnah's Press conference at his Bombay home on Malabar

Hill, in late July 1946, marked the public turning point. It was so unusual for

the Quaid-i-Azam, or 'Great Leader', to call a Press conference that both foreign and Indian

reporters rushed eagerly to attend it. Nor were they disappointed: Jinnah

intimated—rather boldly—the coming of Direct Action Day. Two and a half Weeks later

this day touched off a chain of events that led, after

twelve explosive months, to a divided India and the violent

disruptions of the Great Migration.

Until then most of us had thought the differences between

the Congress Party and the Muslim League would somehow be resolved and that

freedom would bring a united nation, Jinnah's arguments for division were all

familiar: that the Muslims in India were outnumbered three to one by Hindus and

would be crushed under Hindu domination; that Hindus worshipped the cow while

Muslims ate the cow; that religion, customs, culture all made Muslims different

from Hindus.

Opponents of the two-nation theory maintained that Hindus

and Muslims could not be so different, since there was no racial difference.

Ninety-five per cent of India's Muslims were Just converted Hindus. Even Mr

Jinnah, they were fond of pointing out, had a Hindu grandfather.

For my part, I believe that die tragic weakness of the

Indian leaders during this crucial period was their failure to take a firm

Stand against the forces of Indian feudalism. A spellbinder with slogans found

it all too easy to galvanize the pent-up suffering of centuries into one

powerful current of religious hatred. That this was done by an ambitious lawyer

in Western dress and of un-orthodox habits makes it all the clearer that

religion was used like a document plucked from a briefcase.

There was a good deal of the successful lawyer about Jinnah

that midsummer morning of the press conference, as he stood on the steps of his

spacious veranda receiving the reporters. A pencil-thin monochrome in grey and

silver, with perfectly tailored suit and tie and socks precisely matching his

hair, his manner with us was courteous but formal. As he fitted his monocle to

his eye and began to speak, there was something consciously theatrical about Mr

Jinnah—reminiscent of that most un-Islamic chapter of his past when he was a

Shakespearean actor in England.

His statement to the Press was in the form of a monologue, delivered

in an icy voice, which was a forecast of fiery events to come. 'We are

preparing to launch a struggle. We have chalked out a plan.' We reporters,

although we sat around Jinnah in a close circle, had almost to stop our

breathing to hear his curiously hushed words. He had decided to boycott the

Constituent Assembly. He was rejecting in its entirety the British plan for

transfer of power to an interim government

which would combine both the League and the Congress. He lashed out against the

'Hindu-dominated Congress' in his flat, chilled monotone. It seemed clear, now

the bondage to the British was drawing to an end, that the was free to

concentrate ail his fire against the opposite party.

'We are forced in our own self-protection to abandon

constitutional methods.' His thin lips slit into a frigid smile. 'The decision

we have taken is a very grave one.' If the Muslims were not granted their

separate Pakistan they would launch 'direct action'.

The phrase caught all of us. What form would direct action take,

we all wanted to know. 'Go to the Congress and ask them their plans,' Mr Jinnah

snapped. 'When they take you into their confidence I will take you into mine.'

There was silence for a moment, broken only by the cooing

of pigeons hopping over Jinnah's shaven lawn. Then he added in the same

toneless voice, so strangely unmatched to his words; 'Why do you expect me

alone to sit with folded hands? I also am going to make trouble.'

Next day the Quaid-i-Azam [Jinnah] changed out of his

double-breasted

suit and put on Muslim dress and fez for die Muslim masses. Standing on a

platform liberally decorated with enlargements of his portrait, he announced

that the sixteenth of August, two and a half weeks hence, would be 'Direct

Action Day'. His vituperation against die Congress was acidly explicit. 'If you

want peace, we do not want war,' he declared. 'If you want war we accept your

offer unhesitatingly. We will either have a divided India or a destroyed

India.' And the Muslim Leaguers Jumped up on their sears and tossed their

fezzes in the air.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Bombay, lat

July 1946

(source: pages 25-27 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

Run-up to direct

action

It was a battle between politicians now. The papers blazed

with accusations from both sides—League and Congress equally intolerant in

their attacks. The opposing streams of fiery words had a terrible effect on die

emotional Indian people. Passions mounted during the crucial fortnight; Direct

Action Day dawned in an atmosphere of dread and foreboding.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 27 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

she felt they were preparing

for some religious procession

On August 16, our domestic help told my mother that while walking to our place through the slum, she had seen some of the residents assembling and sharpening knives and sticks. As this was not as uncommon sight during Muharram, she felt they were preparing for some religious procession. She did not even know that the Muslim League had declared a Direct Action Day in support of its demand for Pakistan. No one took the declaration seriously till suddenly in late morning, before our unbelieving eyes, Calcutta exploded. Mobs that had collected in front of the slum began to beat up Hindus; in the distance we could see houses being set on fire and looted. That was my first exposure to the politics of slums in South Asia and rioting as a crucial component of that politics.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 2 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

TheHindu community conspired

to pre-empt this move

When the Quaid-i-Azam called for the Direct Action Day, the well-organized Hindu community conspired to pre-empt this move. They were supported by the British Inspector-General of Police.

Roquyya

Jafri, Position.

Calcutta, 1946

(source Roquyya Jafri : “A model of political rectitude.” http://www.dawn.com/2003/09/08/op.htm)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Roquyya Jafri)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16-19 August 1946 - Great

Calcutta Killings

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

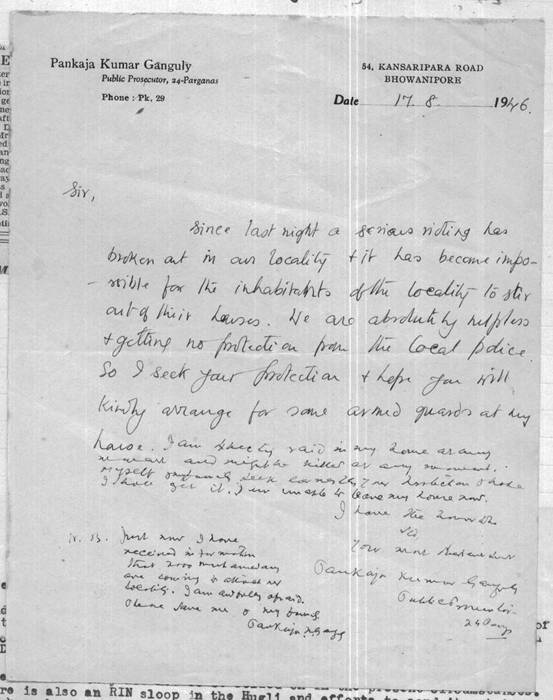

A serious rioting has broken out in our locality

Sir,

Since last night a serious rioting has

broken out in our locality + it has become impossible for the inhabitants of

the locality to stir out of their houses.

We are absolutely helpless + getting no protection from the local

police.

Sop I seek your protection + hope you will

kindly arrange for some armed guard at my house.

[…]

Pankaja Kumar Ganguly,

Public Pprosecutor 24 Parganas,, Calcutta

(source: personal scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on

20-Dec-2005 / Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Direct

Action

India suffered the biggest Moslem-Hindu riot in its history. Moslem League Boss Mohamed Ali Jinnah had picked the 18th day of Ramadan for "Direct Action Day" against Britain's plan for Indian independence (which does not satisfy the Moslems' old demand for a separate Pakistan). Though direct, the action was supposed to be peaceful. But before the disastrous day was over, blood soaked the melting asphalt of sweltering Calcutta's streets.

Rioting Moslems went after Hindus with guns, knives and clubs, looted shops, stoned newspaper offices, set fire to Calcutta's British business district. Hindus retaliated by firing Moslem mosques and miles of Moslem slums. Thousands of homeless families roamed the city in search of safety and food (most markets had been pilfered or closed). Police blotters were filled with stories of women raped, mutilated and burned alive. Indian police, backed by British Spitfire scouting planes and armored cars, battled mobs of both actions. Cried Hindu Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (who is trying to form an interim government despite the Moslems' refusal to enter it): "Either direct action knocks the Government over, or the Government knocks direct action over."

By the 21st day of Ramadan, direct action had killed some 3,000 people and wounded thousands more. Said one weary police officer: "All we can do is move the bodies to one side of the street." Vultures tore into the rapidly putrefying corpses (among them, the bodies of many women & children).

Like other Indian leaders, Jinnah denounced the "fratricidal war." But most observers wondered how Jinnah could fail to know what would happen when he called for "direct action." Shortly before the riots broke out, his own news agency (Orient Press) reported that Jinnah, anticipating violence, was sleeping on the floor these nights—to toughen up for a possible sojourn in jail.

(source:

TIME Magazine, New York, Aug. 26, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

The Start of the’Day of

Direct Action’

On 16th August, in the morning from about 6.00 am, gatherings of Muslims, 200-400 strong and armed with lathis wended their way towards the Calcutta Maidan, marching like soldiers, four abreast. They gathered at the foot of the Ochterlony Monument. Fiery speeches were made, chiefly directed against the Hindus, but the Hindus did not turn out to listen to the speeches. However, what happened to them in their homes and shops was quite another matter.

Here mobs of people, dressed in all kinds of costumes, had begun plundering, raping, burning and killing the Hindus! Private houses and shops were set on fire. The usually peaceful Hindus were so taken aback by this sudden onslaught that they totally failed to protect themselves. They had hoped for protection and relief from the Police.

No help came, however. Though the Police were out in great force, the attacks were so widespread, that they were totally outnumbered. The raping, robbing and arson went on throughout the day, but a strange fact remained: not a single Muslim shop or house suffered any molestation!

The leaders of the different mobs of Muslims carried on the lapels of their coats Mr Jinnah's sign: the crescent moon and star. It was obvious who stood behind the horrible thing. In my office throughout the day, I heard news of the terrible happenings from all parts of the city, especially the Hindu localities.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, 16th August 1946

(source: page 211 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

“There is a Mussulman shopkeeper standing in

front of me…”

Later in that year came what is still known in Calcutta as 'The Great Killing', when Hindus and Muslims, on the verge of Independence, killed one another by the thousand. Corpses lay rotting in the streets or were crammed down the man-holes to block the drains. Now it was crowds fleeing from Calcutta who drifted helplessly down the road past the compound, 'At this moment,' Father D. wrote, “there is a Mussulman shopkeeper standing in front of me, weeping intermittently, of course, and telling me that his father has been killed by the Punjabis, his shop looted, and that he wants me to help him to get to his country. The worst of it is that it is impossible to help to any good, and it is impossible to know whether he is telling the truth or not. But I think he must be, for he says he is willing to go over and eat rice.” At the end of his letter he adds, “My Mussulman has just come across from the kitchen, quite replete and most grateful, and he has gone off leaving me most thankful that I did not send him away uncared for.”

Friends of Father Douglass,

Missionaries and Charity workers in Behala, Calcutta, 1946.

(Source: Father Douglas of

Behala. London, 1952 / Reproduced by courtesy of Oxford University Press)

“Poor Gangaram’s face was crawling with flies and

cockroaches!”

When

Jinnah launched his Direct Action Day we were in Poona. The full horror of the

mass killings which took place in Calcutta did not hit us until we got back to

Delhi. My friend Stella had fled after finding the head of her peon on her

desk.

“Poor Gangaram’s face was crawling with flies and cockroaches! My papers were soaked in blood, a whole month’s work destroyed! There was blood everywhere. Taya, you won’t believe it, the streets were full of bodies. And the police were doing nothing, absolutely nothing., just looking the other way. It was unbelievable! Unbelievable!” Estimates of the dead ranged form four thousand five hundred to thirty thousand. The Muslim Chief Minister of Bengal had planned the massacre. By the third day, Calcutta’s tax drivers, most of whom were Sikhs, had organised themselves and, with the help of Hindus, went on the rampage, killing Muslims in retaliation. It was an inexcusably long week before the British Governor, an ex-trade-union official, called in the army.

Taya Zinkin, Wife of an ICS

Officer. Calcutta, Summer 1946

(source: Taya Zinkin “French

Memsahib”Stoke Abbott: Thomas Harmsworth Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Taya Zinkin)

People had been jumping over

our walls,…

“We

were not suppose to go out into the streets, but I went anyway. Then I saw the bodies on the streets, stabbed,

beaten, lying there is strange positions in their dried blood. We had been behind our safe walls. We knew that there had been rioting. People had been jumping over our walls, first

a Hindu, then a Muslim. You see, our

compound was between Moti Jhil, which was mainly Muslim then, and Tengra with

the potteries and tanneries. That was

Hindu. We took in each one and helped

him to escape safely. When I went out in

the streets -- only then I saw the death that was following them. “

Sister

Teresa, Teacher at Loretto School. Calcutta, August 1946

(source:

Anne Sebba: “Mother Teresa 1910-1997 Beyond the Image”London: Orion, 1998)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Anne Sebba)

Nanda Lal’s

Teashop

Most of what I learned about that day came from a little

tea-shop keeper in Calcutta, where the explosion began. As soon as I heard of

the incredible events taking place, I had flown from Bombay to Calcutta. The

disruption of normal city life was so great that it was some time before I could make my way to the

ruined heart of the bazaar district. Hunting for a survivor who had been an

eye-witness to the first stroke of direct action, I found Nanda Lal, in the

wreckage of his teashop.

Nanda Lal's little 'East Bengal

Cabin', at 36 Harrison Road, was located in one of those potential trouble

spots where a by-lane of Muslim shops crossed the Hindu-dominated thoroughfare.

Nanda Lal was a Hindu and wore

the traditional dhoti, twisted diaperlike between his legs. A patch of grizzled

hair stood out on his walnut-coloured chest, and a narrow silver amulet gleamed

on his thin upper arm. Like many Bengalis, he was fairly well educated and

spoke a little English.

The 'East Bengal Cabin', with its

elongated oven fronting the pavement, looked much like an Asiatic version of a

Nedick's stand. The Hindu clerks of the Minerva Banking Corporation opposite

were frequent customers, as were the boarders in the 'Happy Home Boarding

House' near-by. Although Nanda Lal was in the protective shadow of these

impressive Hindu establishments, the Muslim quarter began just round the comer

in Mirzapore Street, too close for security,

On the morning of August 16th,

Nanda Lal started his oven and set out his tray of sweetmeats as usual. When

his little son came out with the jars of mango pickle and chutney, he commented

to the child that the streets looked reassuringly quiet. The sacred cows that

roam freely through the thoroughfares of Calcutta were sleeping as usual in the

middle of the car tracks, and rose to their feet reluctantly, as they always

did, when the first tramcar of the day clanged down Harrison Road.

It was the sight of that first

tram that confirmed Nanda Lal's fears that this day was to be unlike all other

days. Normally it was so crowded that they bulged from the platform and clung

to the doorsteps and back of the car. Today there was hardly a passenger on

board.

Then things began happening so quickly that Nanda Lal could

hardly recall them in sequence. But he did remember quite clearly the seven

lorries that came thundering down Harrison Road, Men armed with brickbats and

bottles began leaping out of the lorries—'Muslim 'goondas', or gangsters, Nanda

Lal decided, since

they immediately fell to tearing up Hindu shops. Some rushed into the furniture

store next to the 'Happy Home' and began tossing mattresses and furniture into

the street. Others ran toward the 'Bengal Cabin', but Nanda Lal was fastening

up the blinds by now, shouting to his son to run back into the house, straining

to bar the windows and close the door.

He could hear a pelting sound

beating up the street, the hammering noise of a hail of stones. He was too busy

getting the •windows barred to take much notice of the fact that he was hit in

several places and his leg and head were bleeding. He managed to get inside by

the time the ruffians reached his shop; he could hear them banging against his

door as he double-barred it from the inside; then he raced across the inner

courtyard.

The court was edged with

tenements and closed from the outside by a wall. Nanda Lal could hear goondas

climbing the wall, shouting; 'Beat them up! Beat them up!' A head rose over the

wall, and then several figures started pulling themselves up into view. But by

that time some of Nanda Lal's numerous relatives, who lived in his flat, had

taken up a counter-offensive from the terrace and the invaders were driven back

under a shower of flower pots.

In the breathing spell offered by

this successful move, two of his wife's uncles ran down and helped Nanda Lal

build a barricade at the foot of the stairs which would jam shut the door

leading to their flat. Whatever benches

and tables they could lay their hands on, they piled against the door and at

the foot of the stairs. Nanda Lal snatched three bicycles from the vestibule

and jammed them in amidst the furniture. Then they all ran up to the top floor

of the flat, where the women of the bouse were huddled in the upper hallway.

Nanda Lal peeped cautiously out

of a window. Never had he seen the streets so filled with clawing, surging

mobs. In front of the Happy Home, some broken rickshaws had been added to the

heap of mattresses, and flames were rising from the pile. When the wind shifted

the smoke, Nanda Lal could glimpse figures on the bank steps shaking up pop

bottles and hurling them into the crowds'—the bottles bursting like hand

grenades when they landed. Flames were racing through the dress goods swinging from racks in front of the 'Goddess of Plenty' dress shop

and through the crowded living quarters behind the rows of shops.

Nanda Lal suspected that much of this was the organized

work of goondas. In India 'goondaism' is a profession; goondas abound in a port

city such as Calcutta, where they do a brisk trade in smuggling but may also be

hired for strike-breaking or religious outbreaks.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: pages 27-9 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

The battle for

Ripon College

Later in die morning Nanda Lal climbed to the roof. Looking

down, he saw boys, wearing the green arm-bands of Muslim League volunteers,

weaving their way through the crowds and heading toward Ripon College. Drawn in

a new direction, the entire mob began pressing down Harrison Road toward the

college.

Like all Indian colleges, Ripon had long been a crucible of

seething politics. With the recent emphasis on Hindu-Muslim differences, the

religious fanaticism infecting politics had had explosive effects on the

students. The violent fighting at the fortress-like base of the college, one

street away, was hidden from Nanda Lal's view, but he could see a desperate

battle in progress on the roof. The skirmish centred about the orange, green,

and white tri-colour of the Congress Parly, which had been raised on the

flagpole by Hindu students early that morning. Through the struggling knots of

youngsters he could catch flashes of green as the opposition beat their way to

the pole with their own Muslim League flag.

Finally the green banner, with its Islamic star and crescent,

shot to the top of the pole, and the muddled shouting of the mob below changed

to an articulate roar. 'Allah ho Akbar.'

('God is great')—the slogan which the Mussulman uses impartially in prayer and

in battle—swept through the streets.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 30 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

Gunfire is rare

in Indian riots

The streets and by-lanes were throbbing with cries of 'Jai Hind.' ('Victory to a united India') from the Hindus, and 'Pakistan

zindabad.' ('Long live Pakistan') from the

Muslims. Suddenly this clash of slogans was punctuated by a new staccato sound.

A rattle of bullets from the window of an apartment opposite the college

brought cold terror to the heart of Nanda Lal. Gunfire is rare in Indian riots.

A new frenzy swept the throng and the riot overflowed the bounds of Harrison

Road. Through the entire city the terror and arson spread, through the crowded

bazaars, the teeming chawls and tenements.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 30 Margaret

Bourke-White: Interview with India. London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

Beseiged upstairs

During the terrible days that followed, Nanda Lal huddled

with his family and relatives in the upper hallway. Sometimes bricks and stones

crashed through the windows of the outside rooms. The children cried a great

deal; they were hungry as well as terrified.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 30-1 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

The rescue of nine Hindu

college girls

One night Nanda Lal had the opportunity to help in the rescue

of nine Hindu college girls. He was astonished that one of his Muslim

neighbours approached him on this project. He had completely forgotten, he told

me, that Mussulmans could be benevolent human beings. The evacuation plan was

worked out by the proprietor of the Gulzar Shawl Repair Company, whose back

alley adjoined that of the 'East Bengal Cabin'. Disguised as Muslims in the

burkas with which orthodox Mohammedan women veil themselves from head to toe,

the college girls were smuggled through the Muslim quarter and into a Hindu

area. The Shawl Repair Company provided the burkas, and Nanda Lal's help was

enlisted in this joint humanitarian project because his courtyard . connected

Muslim and Hindu streets and furnished the girls with a good refuge to don

their disguises.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 31 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

Grandmother was made of

sterner stuff

When the communal riots broke out on August 16, 1946, our area took on a slightly haunted look as if the violence would affect our lives and we had to be prepared for emergencies. There were no Hindus left here once the riots reached their peak, except us.

Grandfather was determined to move out to the Great Eastern Hotel till the madness died down but grandmother was made of sterner stuff. She refused to budge from her own house and preferred to deploy armed guards near our gate. The threats of local Muslims passing by in tongas did not unnerve her in the least. Her will prevailed and we stayed back at No. 6.

Samir Mukerjee. Schoolboy.

Calcutta, August 1946

(source: Samir Mukerjee: Keep

the faith & the friends. The Telegraph: 31Oct2003)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Samir Mukerjee)

“I

was at a loss to understand what was 'going on'”

Although I often recall, not without considerable nostalgia, the old Calcutta days, I cannot forget the terrible toll of lives lost during the pre-independence riots in West Bengal. I can vividly recall witnessing, at first hand, a man being beaten to death by a 'lathi' wielding mob-just outside our verandah at Megna , being just a chokra at the time, I was at a loss to understand what was 'going on' and could only listen wide-eyed to the conversations of the 'bhuda lok' who would, at times, speak in whispers ! Protected, to a fair degree, by the compound's walls I would lie awake at night listening to the shouting gangs, seeing the flickering tights from fires, and even the sound of gun-fire close by - all very frightening for all concerned, and especially so for those poor souls in the bazzars.

Kenneth Miln, son of a ‘jute

wallah’. Jagatdal/Calcutta, 1945-49

(source: Letter sent to

us by Mr Kenneth Miln himself, July

2006/ Reproduced by courtesy of Kenneth Miln)

A Hindu milkman

A Hindu milkman was chased by miscreants in front of our

house and while he was climbing over our gate to jump into our compound, he was

repeatedly stabbed. This caused some commotion in the area.

Samir Mukerjee. Schoolboy.

Calcutta, August 1946

(source: Samir Mukerjee: Keep

the faith & the friends. The Telegraph: 31Oct2003)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Samir Mukerjee)

… a black day in the history

of India

16 August was a black day in the history of India. Mob violence unprecedented in the history of India plunged the great city of Calcutta into an orgy of Bloodshed, murder and terror. Hundreds of lives were lost. Thousands were injured and property worth crores of rupees was destroyed. Processions were taken out by the League, which began to loot and commit acts of arson. Soon the whole city was in the grip of goondas of both the communities.

Sarat Chandra Bose had gone to the Governor and asked him to take immediate action to bring the situation under control. He also told the Governor that he and I were required to go to Delhi for a meeting of the Working Committee. The Governor told him that he would send the military to escort us to the airport. I waited for some time but nobody arrived. I then started on my own. The streets were deserted and the city had the appearance of death. As I was passing through Strand Road, I found that a number of cartmen, and darwans were standing with staves in their hands. They attempted to attack my car. Even when my driver shouted that this was the car of th Conress president, they paid little heed. However I got to Dum Dum with great difficulty just a few minutes before the plan was due to leave. I fond there a large contingent of the military waiting in trucks. When I asked why they were not helping to restore order, the replied their orders were to stand ready but not to take any action. Throughout Calcutta, the military and the police were standing by but remained inactive while innocent mn and women were being killed.

Maulana Azad, president of

Indian National Congress. Calcutta, 1946

(source page 169 Maulana

Abdul Kalam Azad: “India Wins Freedom” London: Orient Longman, 1988.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Orient Longman 1988)

In no time, there were about

200 families on the lawns.

The

YMCA building had a high wall separating it from the middle-class Hindu

localities to its right. The workers at the YMCA – gardeners, guards, and

cooks, both Hindus and Muslims – quickly put up ladders there and brought in

the frightened residents. In no time, there were about 200 families on the

lawns. The main door of the building was closed. That effectively contained

violence in the immediate neighbourhood.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 2-3 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

the streets belonged to the

mobs

But

the streets belonged to the mobs. I could see in the mobs familiar faces, now

trying to look very heroic. But they also seemed to have found a chance to give

petty greed a new ideological packaging and a new, a more ambitious range. They

would beat up the Hindu passers-by, depriving them of their money and watches

and, in one or two cases, even knifing them.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 3 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

A Looting in Bentinck Street

On my return home from the office, I had a cup of tea and decided to go and have a look at the holocaust. I proceeded up past Government House, Esplanade East to the crossings of Chowringhee, Dharamtola and Bentinck Streets. There I saw the first Police squad. They had a Police motor truck with them and all were armed with revolvers, but they just stood looking at the plundering being done and took NO action whatsoever!

Suddenly, the mob began to hack the padlocks of a Hindu shop on Bentinck Street. I knew the owner of the shop, a poor Hindu, who had worked himself up from a street hawker of pan bidi to a more-or-less prosperous shopkeeper. He was not present, having fled for personal safety after padlocking his shop - a general store full of all kinds of grocery and tin provisions, plus cigars, cigarettes, tobacco, etc.

In a few minutes the axe they used had broken the padlocks and the expanding iron doors were pulled aside, with the plunderers, in full cry, running away with the contents. I had, while the breaking in was going on, gone over to the Police squad and remonstrated them for their inactivity.

On my threatening 'more will be heard of this,' they drove the truck over to the shop and arrested about a dozen looters, their arms full of loot. Among them was an Anglo-Indian, of a ne'er-do-well type. The Police drove away with them, leaving the shop wide open and no Police to guard the shop.

I pulled the expanding iron doors together at once. As locking them was impossible, I stood with my back to the doors. The would-be looters formed a half-circle in front of the shop and began abusing and taunting me. They had not the pluck to attack me, however. I waited, expecting some Police would come back to the crossing again. Instead, a large mob of Muslims, under an old, bearded leader with Jinnah's crest on his coat, turned up.

There were about 200-300 of them. The old fellow came up to me and asked why I stood there protecting the shop which had been broken into by Muslim looters. 'You better go away,' he said.

'Do you mean to tell me that it's the order of Mr Jinnah to carry on in the way things have been going on all day?' He gave me an angry look. I continued, however: 'If it's not your Mr Jinnah's order of the day, by his direct-action method, then YOU show me YOU can guard this shop from further looting and I will go away.'

About half a dozen of his followers had worked their way behind me while this interlude took place. Though I heard no order given by the old leader, he must have done so by a wink of his eye, because, the next second, about five or six lathi blows rained down on my bare head! God must have provided me with a fairly thick skull, because, though each blow had a stunning effect, I did not fall, but withstood the terrible blows!

Of course, my scalp was cut by each blow and blood streamed down my face and neck. How many more blows I could have taken without dropping must be left to conjecture. The proverbial Indian superstition saved my life, however, for, suddenly, one of the attackers cried out:

' We are not hitting a man! He must be a spirit or he would have collapsed!'

On that, they ceased belaboring me and, though beaten badly, I walked away - a thing I had never done before!

Discretion was the better part of valour in that instance. Firstly, I was not fighting fit; and, secondly, there were not only the half-dozen who had assaulted me, but 200-300 behind them! As I slowly walked away, I turned and sadly looked back. The shop was again full of looters, running away with my poor friend's goods. There is no doubt in my mind that the seemingly orderly mobs who kept going and coming along the streets were, in fact, there for the purpose of protecting the looters!

On my way home I called at the Norwegian Reading Room. The Reverend and Mrs Koleros were very shocked upon seeing the bloody mess I was in and wanted to attend to me at once. I declined their kindness because I had merely gone there to use them for evidence should I need it.

On arrival in my apartment, I smeared my head with soda powder, and then went under the shower. It burned fearfully, but no-one could tell what impurities might have been on those lathis. After having washed blood and soda off well, I dressed again, tied the four corners of a handkerchief and put it on as a cap to conceal my cut and bloody scalp. Then I went out again, which was then about 7.00 pm.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, 16th August 1946

(source: pages 211-213 of

August Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947”

London: BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

The street was littered with

dead bodies

I came out and walked down Dharamtola. It's hard to describe the sights that met my eyes. Dead bodies lay here and there - poor Hindus who had tried to protect their shops and belongings! Fire was smouldering here and there where the looters had set fire to the empty shops and houses!

I turned onto Willisby Street. Most of that street consisted of furniture shops. The street was littered with dead bodies and burned furniture! I saw Hindu women lying nude in the gutter with bamboo poles stuck up their wombs! If it had been done before or after death, who could say. The place was desolation and ruin everywhere! It was a terrible, fearsome sight!

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, 16th August 1946

(source: page 213 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

‘We certainly did not feel

safe’

We certainly did not feel safe and would have been attacked if the mobs had turned against us. There were Muslims coming off the ships in the Hooghly and walking up Clive Street, not knowing that anything terrible was happening. Before they had gone a few paces they were set upon by Hindus yelling 'Jai Hind' who then butchered them on our doorstep. My husband phoned the police and got a police sergeant who was in a terrible state of hysteria and said there was nothing he could do. The Muslims and the Hindus were looting the city, he said, and setting it on fire and people were murdering one another. That was completely obvious to us; we saw it all. We lived in a Hindu area and at night, all night long, the people in the go-downs round about shouted almost like jackals, 'Jai Hind'. In a high-pitched tone, it was really very frightening, the whole night long, 'Jai Hind'. It was horrible, it really was.

Sheila Coldwell, wife of a

management agency employee, Calcutta, August 1946

(source: page 136-137 of Trevor Royle: “The

Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Authorities' actions

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about

1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

Policemen in mufti

My father’s friend, A.H.M.S. Doha was the deputy

commissioner of police (south) and he took the trouble of sending us policemen

in mufti at night to guard our house. They allayed our fears to a very large

extent and we were very grateful to our Muslim friends for appreciating our

dilemma and emerging as models of reassurance.

Samir Mukerjee. Schoolboy.

Calcutta, August 1946

(source: Samir Mukerjee: Keep

the faith & the friends. The Telegraph: 31Oct2003)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Samir Mukerjee)

The radio worsened things

The

radio worsened things. Being government-controlled, it gave censored news.

Though even that was fearsome, few believed what they heard. They relied on

even more fearsome rumours, especially since, in other respects, the

information given over the radio did not fit what they themselves were seeing.

These rumours further intimidated the residents of mixed localities, and

minorities began to move out of them, ghettoising the city even more.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages3 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

police openly partisan

We

also found the police openly partisan.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Defence

Associations

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about

1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

'Hey, Mister, what's wrong

with you Hindus?’

[…] I went out again, which was then about 7.00 pm.

I proceeded to the Bristol Hotel. There I called up a very influential Hindu on the phone: 'Hey, Mister, what's wrong with you Hindus? Have you become demoralized, or are you all a lot of cowards? Are you going to lie down while the Muslims kill you all?'

'Is that you, Hansen?' came the reply.

'Don't worry, old boy. Wait an hour or so and you will see that we Hindus are not cowards!'

[…]

I retraced my steps back to Chowringhee and down towards Government House. It was about 8.30 pm. Suddenly, from the south, up along Red Road, came lorries, buses, taxis and private cars - all loaded with Hindu warriors: Sikhs, Rajputs, Jats and other up-country Hindus, all armed with a medley of miscellaneous weapons. They all drove past Government House towards the northern part of town, towards the Muslim centres at Canning and Calootola Streets, Zakaria Street, etc. I followed on foot.

When I got to the above-mentioned streets, a terrible sight met my shocked eyes! The Hindus were taking their revenge and every Muslim they could find was slaughtered mercilessly! Blood flowed like water in the gutters, but no dead bodies were lying about. They had opened the manholes of the sewers and as the Muslims were being caught and slain, they were flung down there. About 10,000 to 15,000 Muslims were disposed of during that horrible night!

When day dawned, the Hindus had won the day, but the man they sought most of all - the Muslim Sheriff of Calcutta - had escaped. It was later learned that he, as a loyal lieutenant of Mr Jinnah, had stood behind the whole, disgusting deed, and had hidden himself in the control room of the central Police Office.

August Peter Hansen, Customs

Inspector, 16th August 1946

(source: pages 213-214 of

August Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947”

London: BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

The Fight-Back

Estimates of the dead ranged form four thousand five hundred to thirty thousand. The Muslim Chief Minister of Bengal had planned the massacre. By the third day, Calcutta’s tax drivers, most of whom were Sikhs, had organised themselves and, with the help of Hindus, went on the rampage, killing Muslims in retaliation. It was an inexcusably long week before the British Governor, an ex-trade-union official, called in the army.

The Calcutta Killings triggered off a pendulum of retaliation which kept swinging, with escalating horror, to culminated, almost to the day , a year later in the partition riots.

In the end, more Muslims than Hindus and Sikhs had been killed in Calcutta. So Hindus were attacked in Noakhali, a remote district in East Bengal.

Taya Zinkin, Wife of an ICS

Officer. Calcutta, Summer 1946

(source: Taya Zinkin “French

Memsahib”Stoke Abbott: Thomas Harmsworth Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Taya Zinkin)

the Hindus had organised

themselves and begun to counter-attack

Within

two or three days the Hindus had organised themselves and begun to

counter-attack. Earlier they were a majority but only theoretically. Thanks to

the riots, they began to see themselves as part of a larger formation and, for

the first time, we were treated to the spectacle of a Hindu nation emerging in

Calcutta. The lower caste musclemen and the criminal elements, apart from

castes with low-status vocations such as butchers, blacksmiths and fishermen,

and even upcountry Hindus, Sikhs and Nepali Gurkhas, previously considered

social outcasts or outsiders, became the heroic protectors of middle-class,

sedentary, upper-caste Bengali Hindus. What the Hindu nationalists could not do

over the previous one hundred years, the Direct Action Day had done. Many years

later, when I read that international wars created nations, it did not sound a

cliché. I knew exactly what it meant.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

Badurbagan Sporting Club

There

was a neighbourhood football club, Badurbagan Sporting Club, which occasionally

used to visit the YMCA to play friendly matches with us. Usually it was

football, but sometimes cricket and basketball too. They always were a much

better team and defeated us virtually every time, except in basketball. We had

a natural advantage in basketball, because they did not play it much. But they

were also an exceedingly friendly lot and we used to love their company. The

members were mostly in their teens and they all belonged to the Hindu

neighbourhood diagonally opposite our home and sandwiched between two

non-Bengali-speaking Muslim communities. The riots turned the club into a new

kind of formation. They became the protectors of their community and some of

them openly and proudly turned into killers. The community, too, began to look

at them as self-sacrificing heroes.

Such new heroes mushroomed all over Calcutta, the reprisals they visited on the Muslims were savage.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 3-4 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

literally stoned to death

[…],

the reprisals they [self defence groups] visited on the Muslims were savage. We

saw an old Muslim driving a horse-drawn carriage being literally stoned to

death. It was a devastating experience.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 4 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

no hostility between the

communities within the building

The

YMCA building now had to house, on another floor, a huge number of Muslim

families. Strangely, there was no hostility between the communities within the

building, among either the riot victims or those serving them.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy,

Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 4 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

…, so I remained as one

dead,…

On the following days, 17th-20th of August 1946, many Muslims suffered with their lives. One poor fellow, who had hidden away in some building on Dalhousie Square near Clive Street, came running out as I passed. Some Hindus saw him and came to the attack at once. Poor fellow threw himself at my feet for protection, but 1 could do nothing for him.

They dragged him away from between my legs and smashed his head with such violence that his blood splashed onto my legs! I had to pass on as if nothing had happened because they did not interfere with Europeans as long as they kept to themselves.

On the following day - as far as I remember, it was 19th August - an elderly Muslim came running from Bankshall Street onto Hare Street, not twenty yards in front of me. He was knocked down for dead and dragged to a sewer grating so his life's blood could flow down there. On passing, I noticed he was still breathing, so I went into the Reserve Bank and rang for an ambulance. They came and removed him and he recovered.

He came to my office about two weeks later and thanked me, saying: 'When you bent down over me, I recognized you, but was afraid to move for fear I might be assaulted again. I even heard you call to the guard at the Bank to send for an ambulance, so I remained as one dead until it arrived.'

August Peter Hansen, Customs Inspector,

19th August 1946

(source: page 215 of August

Peter Hansen: “Memoirs of an Adventurous Dane in India : 1904-1947” London:

BACSA, 1999)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with 1999 Margaret [Olsen] Brossman)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Working for Peace

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

A

couple of times he was threatened with death

My father showed remarkable courage all through

those days. A couple of times he was threatened with death. Twice, he was shot

at, once when he had aggressively asked the police to be firmer with the

rioters. Indian police had not yet been toughened up by their encounters with

militants of all hues and could still be relied upon to miss.

Ashis

Nandy. Schoolboy, Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 4 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

A

local peace committee

During the 1946 riots

mentioned above, grandfather along with our neighbours became members of a

local peace committee. Some of these meetings were held in grandfather’s

library where a representative from Bishop’s College and Father Dotaine from

St. Xavier’s Hindu Hostel opposite our house were invariably present. We used

to hear the names of Khokababu and Lal Mian, influential lower-rung Muslim

leaders in our area, bandied about by our elders.

Samir

Mukerjee. Schoolboy. Calcutta, August 1946

(source:

Samir Mukerjee: Keep the faith & the friends. The Telegraph: 31Oct2003)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Samir Mukerjee)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

19 August 1946 - British

troops enter Calcutta to end the riots

_____Pictures

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about

1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

‘…we wept tears of joy and

pride’

They [the British troops] marched down Clive Street and they were singing 'It's a long way to Tipperary'. I may be accused of sentimentality but we wept tears of joy and pride and a great thankfulness engulfed us.

Sheila Coldwell, wife of a

management agency employee, Calcutta, August 1946

(source: page 136-137 of Trevor Royle: “The

Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

'the most unpleasant part of

my military service'

For the first couple of days we didn't know what was happening or who was doing all the mischief. During the day it was quite calm on the surface but it was at night that the troubles would start. There was a lot of arson, a lot of shouting and my battalion was fully stretched: we used to patrol the whole night through to try to control the situation . . . the main thing was that it was a communal riot, one community wanted the other out because by then partition was expected and it was anticipated that the whole of Bengal would go to Pakistan.

Das, Indian Army Officer (of

the Rajputana Rifles) commanding a Punjab battalion, Calcutta August 1946

(source: page 135-136 of Trevor Royle: “The

Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

doing riot duties

In 1945 I was shipped to India to join my unit, who were

being re enforced after great losses in Burma, then came the atom bomb and

everything changed, for the beter I guess, because I am here today.With the

ceasation of the war, we were back to regular army training, and then came the

trouble with Ghandi etc, and rioting began between the different religious

sects, and our duties changed to trying to prevent this awful blood letting

period.The worst of which happened in Calcutta in 1946, to which we were

shipped. When this finally stopped we went back to our barracks in Rawalpindi,

where we remained, still doing riot duties until Britain gave India her

independance in 1947.My regiment was the first British army unit withdrawn from

India and returned to England on the Georgic in August 1947.

Jim Cameron

, Army, Calcutta, August 1946

(source: A2169399 India's independance at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Three military

tanks rolled through

On the fourth day Nanda Lal noted that the weapons in the

street fighting had grown heavier. Soda-water bottles had given way to iron

staves, and unfortunately the neighbourhood had a plentiful supply of rails

from the fence surrounding the near-by Shraddhananda Park. Finally, as the

skirmish of the iron pikes readied its fiercest, a convoy of three military

tanks rolled through and machine-gunned the mobs, and along with them the

police made their belated appearance.

The police had refused to come out without military escort.

In the past their loyalty had been to the King and they had quelled

demonstrations in which their own countrymen, both Hindu and Muslim, were

demanding Independence, and now they feared their own people might turn against

them. When the militia was at last ordered out—and when Muslim and Hindu

leaders finally set aside their own differences and made joint appeals—the

riots began dying down.

Margaret Bourke-White, journalist and travelwriter. Calcutta, 1946

(source: page 31 Margaret Bourke-White: Interview with India.

London: The Travel Book Club, 1951)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Margaret Bourke-White 1951)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gandhi

fasts for peace

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

it

electrified the city

The riots would not have stopped easily in

Calcutta but for Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He undertook a fast unto death in

one of the worse affected localities of the city. No one thought the fast would

work. Some of our elders in school were openly sarcastic. But it did work. In

fact, it electrified the city. The detractors, of course, continued to say that

had he not fasted, the Muslims would have been taught a tougher lesson. But

even they were silenced by the turn of events.

Ashis

Nandy. Schoolboy, Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 4 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

The

many roles of H.S. Suhrawardy

One person who moved closer to Gandhi at the

time was H.S. Suhrawardy, leader of the Muslim League and Chief Minister of

Bengal. In many ways, he had precipitated the riots, not perhaps because he

wanted a bloodbath, but because his constituency was mainly immigrant