The Bengal Famine

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home ● Sitemap ● Reference ● Last updated: 11-March-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

The most tragic event of the 1940s in Calcutta was

the Bengal famine of 1943.

Throughout the war increased demand and reduced

supply drove up rice prices. A cyclone in 1942 and forced requisitioning for

the forces as well as hoarding by speculators then drove prices even further

until they were out of reach for much of the poor.

Many of the starving villagers started a long march

to the city in hope of finding food.

Many died on the way, but a hundred-thousand

settled on to the city’s pavements to beg search for scraps and often simply

die where they were.

The response of the city was inadequate and public

anger rose.

Many volunteered to help the poor in running soup

kitchens many were stirred to political action. But nonetheless about a

thousand destitutes died each week in the streets of the second city of the

empire and all over Bengal there were at least 3 million victims.

Many tried to ignore and forget the catastrophe,

but in the end the consciousness and political outlook of the city had changed

forever.

Who remembers

'how many people remember or have even heard of the Bengal famine of 1943'.

John Christie, civil servant, Calcutta, late 1940s

(source: page 107 of Trevor Royle: “The Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Underlying reasons

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

The Card

BOMBAY is, we believe, the first Indian city to introduce rationing of foods stuffs on an all-out basis. Food-grains as from May 2, are procurable only in authorized shops, which number about 1,000 and on production of ration cards. India is gradually experiencing more and more the inconveniences which Britain and the Continent of Europe have felt almost since the start of the present conflict.

More Indian cities, towns and perhaps villages may soon come under rationing if the present widespread food-shortage, mal-distribution and greed of tradesmen continue to distress the people. Calcutta's plans are maturing and it should not be long before food cards are available to every householder in the city.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, May 6, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Second City

CALCUTTA is known as the Empire's second city. Accumulating administrative incompetence or confusion over its affairs has now attained such proportions as to become, in .our judgment, an Imperial scandal.

Coal-shortage may check supply of electricity to her Industries. Food-shortage and rocketing prices for essentials are and have been worse in and around Calcutta than anywhere in India.

That this would probably be so could be foreseen early last year when the enemy was conquering Burma—if only on account of the consequential difficulty over rice. Yet she has lagged months behind her sister-city Bombay in arrangements for food-rationing. She is years behind Delhi in rent-control. Despite perennial effort and outcry by the public-spirited nothing is ever done to remedy the disgrace of her street garbage. Piles of stinking refuse lie uncleared round open bins in her main thoroughfares, surrounded by scavengers, animal and human ; much of it, when at last removed, is forthwith strewn abroad again from uncovered disposal lorries. Even now, despite last-year's official assurances of vigorous i-ridress. swarms. of uncleanly beggars abound, many of them having contagious disease, others lunatic ; at any time citizens may find these pressed into their intimate companionship in air-raid shelters,-and that unpleasant consideration is by no means the only urgent reason for the beggars' removal. Recently also, there has arisen once more grave public reason, to suspect both the quality and continuity of something vital to all, the water supply, owing to reports of breakdown of boilers, inadequate filtering, and labour trouble.

This state of things cannot be permitted to continue. Drastic action has become imperative. Calcutta is full of troops of all .nations, geography has made her an important war-base for Democracy. The next few months are full of serious possibilities. If only for the sake of-efficient prosecution of the war, the city's affairs should be put into tolerable order without delay.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, June 20, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

Important names were mentioned in this connection but the truth never came out

The famine continued and reached its peak in 1943 to claim almost three million victims. It was widely supposed that the famine was caused by speculators buying up all the rice and hoarding it, thus causing the price to rocket and ensuring them a handsome profit. Important names were mentioned in this connection but the truth never came out and no one was prosecuted as far as we knew.

Eugenie Fraser, wife

of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, 1943

(source:page 101 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

_____The loss of Burma_________________________________

_____Food subsidies for Calcutta______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

May 1942 - Boat Denial policy

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_________________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 October 1942 - The Midnapore Cyclone

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Food requisitioning

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

Food to the metropolis

Calcutta needed food. They ordered food to Calcutta. People in the district had no food. It was all going to the city. Indian and British civil servants knew that was not good, but this was the policy. There was nothing they could do against it. Had they protested they would have lost their job.

Ananda Shankar Ray, Indian Civil Service, Early 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 1943 - First reports of famine in the villages

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

May 1943 - The first starving villagers reach Calcutta

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

The two Extremes

I was a member of the Friends' Ambulance Unit - the Quakers. and a small group of us came to Calcutta in May ’42 to help with civil defence.

This was a totally new experience and one which shocked me.

One of the things that shocked me, was to see a dog running along, and in its mouth, it was carrying a child’s head.

Another thing, if you take to the extreme opposite situation, was if one had dinner at Firpo’s, which was the main restaurant in Calcutta then, in one’s nice white dinner jacket, one would be treading over people who where either dead or dying often half naked…

Richard Symonds, Friends’ (Quakers’) Ambulance Unit, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

The pavements and stations were crowded with masses of dejected people

Meanwhile the whole of Bengal was in the grip of a devastating famine. People starving in the villages had rushed to Calcutta only to find the same shortage prevailing there. The pavements and stations were crowded with masses of dejected people, sitting, lying, helplessly resigned to their fate. The number of beggars increased tenfold.

Eugenie Fraser, wife

of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, early

1943

(source:page 100 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

They were completely alone in a small world of their own

One moving scene has remained in my memory of two small boys, maybe four and two years old, sitting close together on the edge of the pavement, the elder tenderly embracing his little brother and trying to tell him something, perhaps a story. They were completely alone in a small world of their own. I placed some money on their laps and walked on. There as nothing I could do.

Eugenie Fraser, wife

of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, early

1943

(source:page 100 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

The man’s face was evil itself

I had been purchasing wool in Dharamtala Steet and was hurrying along the pavement, when my attention was drawn to a man sitting there with a small boy beside him. The child’s head was resting on the man’s lap. The man’s face was evil itself. As I passed the boy raised his head and looked up to me. I had never before seen such grief and resignation in eye so young and then to my horror I saw that both the boy’s hand had been cut off at the wrists. The scarlet scars were still clearly visible. I was shaken to the core of my being. The first impulse was to snatch the child, hold him tight to my breast and run far from this obscene monster – run – but where? Overwhelmed by unbearable anguish I cold only hurry past, crying in hopeless despair, “God, why do you allow this? Where was your mercy?”. These grief stricken eyes stayed with me for a long time and cans till haunt me. “Why is it Mother India, that you – benevolent and kind – are also so coldly indifferent to the cruel exploitation of your helpless little children?”.

Eugenie Fraser, wife

of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, 1943

(source:pages 100-101 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

June 1943 - First reports of death from famine in the villages

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Second City

CALCUTTA is known as the Empire's second city. Accumulating administrative incompetence or confusion over its affairs has now attained such proportions as to become, in .our judgment, an Imperial scandal.

Coal-shortage may check supply of electricity to her Industries. Food-shortage and rocketing prices for essentials are and have been worse in and around Calcutta than anywhere in India.

That this would probably be so could be foreseen early last year when the enemy was conquering Burma—if only on account of the consequential difficulty over rice. Yet she has lagged months behind her sister-city Bombay in arrangements for food-rationing. She is years behind Delhi in rent-control. Despite perennial effort and outcry by the public-spirited nothing is ever done to remedy the disgrace of her street garbage. Piles of stinking refuse lie uncleared round open bins in her main thoroughfares, surrounded by scavengers, animal and human ; much of it, when at last removed, is forthwith strewn abroad again from uncovered disposal lorries. Even now, despite last-year's official assurances of vigorous i-ridress. swarms. of uncleanly beggars abound, many of them having contagious disease, others lunatic ; at any time citizens may find these pressed into their intimate companionship in air-raid shelters,-and that unpleasant consideration is by no means the only urgent reason for the beggars' removal. Recently also, there has arisen once more grave public reason, to suspect both the quality and continuity of something vital to all, the water supply, owing to reports of breakdown of boilers, inadequate filtering, and labour trouble.

This state of things cannot be permitted to continue. Drastic action has become imperative. Calcutta is full of troops of all .nations, geography has made her an important war-base for Democracy. The next few months are full of serious possibilities. If only for the sake of-efficient prosecution of the war, the city's affairs should be put into tolerable order without delay.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, June 20, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Plight of a Province

.SURROUNDED by wheat and fat Punjabis, remote from the war zone, the Government of India apparently little heeds Bengal's lamentable state. For that state Bengal herself is in part blameworthy. Few if any signs of innate greatness, such as these tremendous days in the world's history demand, are discernible among the provincial politicians who have manned her Ministries. Most of their energies from the war's onset have evidently been bent on petty intrigue and acrimony and manoeuvre for the spoils of office. Her permanent officials, whether British or Indian, have shown unmistakable symptoms of infection by the pervasive provincial malaise ; consequently they tend to lack imagination or grip. For incompetence and irresponsibility the Corporation which runs the municipal affairs of her capital is probably unexcelled in all Asia. In such elementary administrative obligations of war-time as food-rationing, rent control, conservancy, water supply, management of vagrancy, Bengal and particularly Calcutta have lagged shamefully behind standards set elsewhere.

But blame for the extremely grave situation now confronting Bengal rests heavily also on the Government of India. The Province's outstanding present problem is food; on that all the other problems hinge.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 8, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Famine's Footprints

UNDER famine, social stability is not possible. Rome's imperial philosopher, writing in the midst of abundance, thought that castaways on a raft should gently and equally share their small store. But what if there is only a scrap, hardly enough for one ? Will not infirm human nature make them fight for it ? When destitution comes, as to' many it has come in Bengal, the first thought is survival for self and children, and many, here as in other lands, will put children before self. Food must be found. Starving villagers, having an old belief that Calcutta is an eldorado, swarm into the city, to compete with the destitute there for the crumbs that fall from any table.

So every hour of the 24 may be seen in Calcutta and other towns, men, women and children lying about the pavements, the footpaths, under trees, lucky if they are sleeping through the hours of hunger, wet, weak and ill, almost hopeless. Those who carry away the dead found in the streets do noble work.

But it may be that a large part of the gratitude felt towards them is for taking away sights that offend the eye or nose.

Food may keep alive. But a little food from time to time will not preserve family life, on which social health rests.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August I5, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The reporting of the Famine

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

It's Here

ON another page we today reproduce more photographs taken in Calcutta, illustrating the plight of a Province once regarded as India's foremost. They are terrible photographs. We publish them with reluctance and after anxious thought believing that to do so is unavoidably our duty. Confronted this year with numerous examples of maladministration in the Empire's "Second City", it has been our experience that until they are discussed in the Press nothing is done. Many, we are aware, will view the photographs with surprise as well as repugnance—not only readers in Northern India (still largely ignorant of Bengal's state) but even in Calcutta. For it is a large city, containing with its industrial off-shoots a population of between 2 and 3 millions, and the comparatively unobservant may still pass through its wealthier quarters without noticing much difference from the rather unattractive normal. But our photographs represent widespread reality in the city's poorer parts. In its semi-rural environs, and throughout the mofussil, conditions so far as we can ascertain, are worse.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 29.1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

The Underfed

At the Viceregal call of the Marquess of Linlithgow, a conference of Indians met this week in New Delhi to devise emergency relief for the underfed. Millions of people were hungry, everywhere over the land the shortage of food was acute.

Tale from the Plains. As the monsoon came to Calcutta, thousands stood in line before food shops and were drenched. Because of the shortage of food in the suburbs, whole families moved in and camped on sidewalks in front of grain shops. In Bijapur district, near Bombay, famine was so severe that livestock died. In Bombay five persons were reported injured in a quarrel over a piece of bread. In the Punjab farmers hoarded their grain, thereby made the bad situation worse. (The price of Punjab village brides had gone up, a sure sign of spreading inflation.) Some maharajas put their elephants out to pasture, or tried to sell them, because elephants in captivity usually get bread as well as sugar cane and hay.

The rise in food prices was matched by the rise in the price of clothing—up 400% to 500%. The cost of local medicines had skyrocketed, the prices of foreign drugs had risen 1,600%. A small class of manufacturers and profiteers was waxing rich, but the wages of white-dhotied workers and of professional people had not registered increases comparable to the rise in the cost of living.

Tale from the Hills. In one corner of India the scene was different. TIME Correspondent William Fisher cabled this report from New Delhi:

"In the hills it is just like the India of the past. War is far away. Of all places in India, the hill stations are the most British. Simla, with its gingerbready shops, its dingy hotels and antiquated houses, is strangely Victorian. Time seems to have stood still since Kim contemplated the twinkling lights of Jakko, and the Phantom Ricksha made its ghostly rounds.

"Mogul emperors had their pleasure gardens by the lakes of Kashmir, but on the whole the hill station habit is something new for the Indians. Only the wealthiest among them can enjoy it, and the place they like best is Mussoorie, the epitome of all that is fast, flashy and fashionable. The hills are for maharajas, their courts and courtesans, for members of the Viceroy's council, and for kings in cotton and jute."

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Jul. 12, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

The photographer’s story

I was 23 and I was in Calcutta where all this happened.

This photo [he shows a picture of a starving women with child lying on the doorsteps of a house] is actually in front of our house.

This was my first acquaintance with the famine that was happening all over Bengal.

It was then, that I realised what was happening.

This woman, so helpless with this little child. And practically no milk in her breast…

This shadow over there [in the corner of the photo] is the gate of our house

[He and some journalists toured outlying villages for Peoples War Magazine]

We looked so fat… It was very distressing.

The people want food and you are pointing a camera at them.

I was told, “your photos will show what is happening” Nobody knew then what was going on. “The photos will be shown all over the world and that will probably help…”

Sunil Janah, Photographer for Peoples War Magazine, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

No

one knows what the British Government did with this footage

In 1943, the year of Bengal famine, the British Government approached Shri B.N. Sircar for a technical crew to document the tragedy. Their idea was to raise famine relief with this footage. Sircar entrusted Baba for this important Government project.

Kamal Bose, who assisted Baba dredges up graphic details of the experience:

"For a fortnight, Bimalda, along with us went around Calcutta shooting. What we saw was unbearable. People cried for a drop of starch. If anyone dropped a crumb of bread, riot broke out between famine victims. Our coverage was gruesomely real. We gave the negative to the Government authorities—but it was never shown. No one knows for certain what the British Government did with this excellent, and valuable documentary footage."

Kamal Bose, Film direction assisted to Bimal Roy, Calcutta 1943

(source pages 40-41 of Rinki Bhattacharya: “Bimal Roy – A Man of Silence” New Delhi: Indus, 1994.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Rinki Bhattacharya 1994)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

August 1943 - Peak of the Bengal Famine

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

The Bengal Famine

WE commend to the Government of India's attention last Friday's powerful statement by Sir Jagdish Prasad, a former member of the Viceroy's Executive Council. In it he declared Bengal to be faced with one of the worst famines in living memory, described the terrible things he had seen during a recent tour in rural areas, suggested some practical remedies, and urged that important men from New Delhi should visit the Province to obtain visual evidence of its condition. This plea we cordially endorse. There has been resentment, at the suggestion lately dropped by a Central Government spokesman in the Legislature that Bengal's distress had been "over-dramatized". The reference was apparently to publication in the Press of photographs. These only came into use when it seemed plain that public speeches, Pros.-; statements, and leading articles in newspapers were having practically no effect on the New Delhi Secretariat's imagination. To save the innocent poor of Bengal in their thousands from death, bereavement, and wretchedness, and to avoid spread of epidemics to the troops in the Eastern War Zone, sharp stimulus seemed needed. We have been glad to discern symptoms of its having gradually had some beneficient humanitarian effect. A remote pachydermatous bureaucracy and an initially somewhat unsympathetic up-country Indian public have alike been stirred.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, September 12,1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

FOR several weeks. Bengal has been in famine's grip.

FOR several weeks. Bengal has been in famine's grip. All the standard clinical signs of this dread social malady of Asiatic lands have been evident; the pitiable wanderings of the emaciated poor in search of sustenance ; the disintegration of family life and attendant evils; the mounting death-roll. Officially recorded weekly mortality from all causes in the Province's capital has now soared to over double the normal. In the week ending September 18 there were 1,319 deaths as against an average of 596 during the corresponding weeks of the previous five years. Since August 16, 4,338 sufferers from starvation have been admitted to the city's hospitals by the police Corpse Disposal Squad and the two non-official agencies in the city since August 1 have been 2,527. Information from which to form any broad picture of conditions in the mofussil is scanty; reliable statistics of mortality there are non-existent. But reports suggest that in many areas rural Bengal is even worse stricken than urban.

This sickening catastrophe is man-made. So far as we are

aware, all of India's previous famines originated primarily from calamities of Nature, But this one is accounted for by no climatic failure ; rainfall has been generally plentiful. What the Province's state would not be had drought been added to Governmental bungling is an appalling thought.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, September 23. 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Here Lies.

THE Secretary of State for India seems to be a strangely misinformed man. Unless the cables are unfair to him, he told Parliament on Thursday that he understood that the weekly death-roll (presumably from starvation) in Bengal including Calcutta was about 1,000, but that it "might be higher". All the publicly available data indicate that it is very much higher; and his great office ought to afford him ample means for discovery. The continuous appearance of effort on the part of persons somewhere within India's Governmental machine, perhaps out here perhaps in Whitehall, to play down, suppress, distort, or muffle the truth about Bengal is dragging the fair name of the British Raj needlessly low. It contrasts most remarkably with the attitude taken during the famines near the end of the last century. Then, in the heyday of British Imperial responsibility, though modern facilities for organization were lacking, no effort was spared to probe and proclaim the truth about any maladministration, so that it might be promptly dealt with and the blot on the honour of the Indian Empire removed.

The Government of Bengal's officially released daily statistics for deaths in hospitals in Calcutta alone during the first 12 days of October among so-called "sick destitutes (the recently invented Governmental euphemism for starvation sufferers) give a total of 918. That works out to an average of 535 weekly for this one big city whose total mortality from all causes during the week ending October 9 was 1,967, which is nearly four times the quinquennial average. (That figure of four times affords ground for wider reflection.) The September total for deaths among sick destitutes in the city was 1,334, making a weekly average of 312. These September and October starvation figures (which it will be noted show a grim progressive rise) are generally supposed to be incomplete, and are known to be so for September owing to the two days' Government blackout then of news.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, October 16, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Bengal Rot

SINCE last year's administrative calamity in Bengal, which brought death to innocents in undiscoverable numbers, but amounting certainly to many hundreds of thousands, India's eyes, indeed the world's, have been watchfully focussed on the Province's handling of affairs. In particular attention has concentrated on conditions in its capital, nowadays widely known, but in the main derisively as the Empire's "Second City". These conditions are regarded, rightly we think, as an index of Bengal's capacity to restore somewhat, under war-time stresses, its besmirched reputation for tolerable efficiency in government.

The problems existing are many and grave. Among them is planned lowering of the present atrociously high cost of common articles of diet other than those few rationed. This, naturally, presents wide difficulties, for it hinges to some extent on all-India questions of inflation and price-control. Some local improvement however should certainly be achievable and is acutely needed, for indications of extensive abnormal malnutrition among the poorer elements of the populace multiply. No othe factor, in our view, can adequately account for the huge difference in Calcutta's civilian mortality this year and during the spring of 1943 before the famine. Weekly recorded deaths nowadays stand on the average at about 1,160 as against 520 last year. The unexplained conspicuous gap gravely perplexes us and some others, as does the astonishing lack hitherto of Governmental or popular comment upon it.

(source: The Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, May 20, 1944)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Ancient III

The filthy, tattered flotsam of Calcutta's normal beggar population has always shocked the Westerner. Today thousands of refugees are streaming into the city from starving Bengal villages. Men, women & children swarm about hotel garbage cans, clawing hungrily over heaps of offal that spread a sickening pall of stench for blocks; Calcutta's hospitals, with beds for only a small percentage of the city's sick, report a score or more of starvation deaths daily. Private agencies feed 62,000 destitutes each day, cannot keep pace with the influx.

Floods destroyed the Bengal rice crop during the last growing season, but they were merely an addition to India's ancient bag of ills. Provinces with plentiful food supplies are indifferent to the suffering of their neighbors. Rice, at six times its normal price, is far beyond the reach of India's unwashed. Wealthy Indians cling to hoarded stocks, awaiting even greater profits.

Last week Bengal officials, seeking help in New Delhi, offered a plan for the systematic housing and feeding of the destitute, and a proposal for repatriating refugees to the villages. Others eyed the Japanese looting of Burmese rice stocks and hoped for a more permanent solution: the reconquest of Burma.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Sep. 20, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

The Raj Has Failed

Smoke pillars writhed skyward last week from Calcutta's five burning ghats. Emaciated Indians shoveled at least 100 Hindu dead into the ancient fires each day. Possibly greater numbers of Moslem corpses were buried, fellow victims of a bitter, ten-month-old Indian food shortage now grown to famine proportions.

Through Calcutta's crowded streets a destitute army over 100,000 strong roamed foodless, homeless, hopeless. Families were jerked apart as mothers peddled daughters for a few rupees. Sons committed suicide to conserve scanty family stores. All around lay the hunger-shriveled dead awaiting, sometimes for hours, the arrival of corpse-removal squads.

In the famine provinces of Bombay, Madras, Bengal, similar scenes prevailed. At the height of India's planting season, hinterland peasantry left their fields.

Voices from India. Famine is no new tale in India. There were hunger plagues in 1867, 1878, 1897, 1900, costing a total of more than 8,000,000 lives. Despite nearly 200 years of British enlightenment, the causes of famine are what they always were: 1) medieval agricultural methods; 2) a population growing more rapidly than wealth and education; 3) Government failure to act.

To these causes can be added one more: Japanese capture of Burma's "rice bowl," from which came 1,500,000 tons of rice annually to supplement India's average yearly production of 27,000,000 tons.

A firm Viceregal program of food control could ease the tragic shortage, feed all. On-the-scene observers believe that incoming Viceroy and Field Marshal Lord Wavell must, on his arrival, take drastic and energetic action. But the soldier-Viceroy long since confessed himself to be a tired old man.

Voices from England. In London, Food Secretary Lord Woolton said that ships were at sea bearing "thousands of tons of cereals" to India. But his words did not allay a nation's conscience. Said the liberal New Statesman and Nation: "The British Raj has failed in a major test. ..." Observed the ultra-Tory Sunday Observer'.

"[Linlithgow's] Viceroyalty, which was to have inaugurated a vast advance in

India's agricultural wealth, unfortunately closes in a clash between rural and urban economy. . . . Somewhere ... we took a wrong turning, probably when we failed to realize that Indian political parties were more pro-Chinese and more anti-Japanese than we were, and had been anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist when we were appeasers. Their desire was to feel that the war was their war, but it still figures as a war to help Britain and save her Empire."

No other voice of influence, in the U.S. or elsewhere, was raised in behalf of famine relief in India until last week, when Australian Prime Minister Curtin said he was arranging to send wheat.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Oct. 18, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

dying

of hunger in front of shops full of edibles

The memory of thousands of people slowly dying of hunger, without any resistance or violence, often in front of shops full of edibles, was still fresh in the minds of the Calcuttans. Most victims were peasants, many of them Muslims. They died without ransacking a single grocery, restaurant or sweetmeat shop.

Ashis Nandy. Schoolboy, Calcutta, 1946

(source pages 1 of Ashis Nandy: “Death of an Empire” in Persimmon. Asian Literature, Arts and Culture (Volume III, Number 1, New York, Spring 200r also www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/03morphologies/ 04death_empire.pdf pp 14-20 Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ashis Nandy)

it was almost impossible to tell the living from the dead

Visits to Calcutta were not all pleasure. Calcutta more than any other city I know has many sides. Poverty and suffering were ever present. The worst happened in 1943 when the great Bengal famine struck. Over a million people died of starvation in Calcutta alone. Visiting Calcutta it was almost impossible to tell the living from the dead in places like Seldar Station. People would be prone on the ground, and leaning against walls, nothing but skin and bone. Carts went around daily collecting bodies for disposal. Some who were still alive got to hospital, but even amongst this favoured few the fatality rate was very high. An acute rice shortage was magnified by merchants holding back supplies for the price to rise. Capitalism rampant. Help was difficult to give, as people would often not eat available food for religious reasons even if it were given and a general air of fatalism was common. This is all history now, so I won’t dwell on it. Famine on such a scale is not common. When something comparable happens today, money, relief foods and drugs are poured in - not always very efficiently or effectively. I am afraid that not much help came to Calcutta and the rest of Bengal. The world was fighting a war and killing was more important than saving life.

Harry Tweedale, RAF

Signals Section, Calcutta, 1943

(source: A6665457 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 11 Pages 85-92 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

August 1943 - Soup kitchens & voluntary aid

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

The Square

This [he is standing in a large central Calcutta square] is a square open area where people could stay. This is why there was a very big gathering of destitutes, of hungry people. This is in the heart of central Calcutta.

Every morning when I used to come here and crossed the square, the footpaths around the square where littered with dead bodies.

I had to cross the dead bodies in order to reach the main road.

One day I could not even cross the square. It was terrible sight. It was just scores of people lying there dead or dying.

I was very young. I used to despair… but my anger was more than my despair.

Otherwise why would I give up my studies? Many of us gave up our studies and went into relief and other activities against famine.

After the famine most of our protest marches started out from here…It had become a kind of symbol... through all this suffering.

Sunil Munsi, Student, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

At the Destitute Relief Kitchen

We expected death from bombing, but not from famine.

We did not even know that a famine was coming, it came so quickly…

Summer’43 we were already in the students’ movement and the women’s movement.

We had organisations to help people, you know

Some people were so poor and so starved, they could not digest.

We were very young and we just could not stand their dying. Even when they had eaten something, they just vomited and died there … you see on the pavement …

[…]

Many people died in spite of what we did, because the people came at the last stage.

This woman was asking for milk “Give me first! Give me first! Because my child is sinking.”

But the people in front of her where also very desperate and they would not let her go.

When it was her turn, she just said “I don’t need the milk anymore…”

She was stiff, just like a stone statue, and everybody looked at the child; and the child was dead.

One particular Lady I remember, she was jagging food from her child.

She was so hungry and she wanted to take that food from my hand, and take it for herself. With her child crying for food…

Gita Banerjee, Activist, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

The mountains of rice in the Botanical Gardens

Eventually we arrived in the Botanical Garden, and a portion of it had been fenced of, to contain the rice which had been bought by the civilian authorities

as well as the military.

And I have to say, that we had a very big army here, as the Japs were on our doorstep and the military were not going to have their Indian troops starve. So they always had to have rice ready to send them.

And the civilian authorities also had to make sure that their important post holders were supplied.

My s husband and the governor said that that was all very well, but we also have to help these people.

And the great battle was then to have some of the rice released.

My recollection was that it was pyramids; laid out on wooden frames, well of the ground about a foot.

Some of the jute bags had given at the bottom, because of the weight and rice had fallen out and you could see the green shoots all around on the ground. I would not like to say how many pyramids there were, but there were a lot.

Sheila Chapman-Mortimer, Calcutta Red Cross Volunteer and wife of the head of Bengal chamber of commerce, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

700 people every day

It was also the place where, in 1943 three million starving Indians had come to die - most of them on our pavements. I would pass the bodies on my way to college. Not something easily forgotten. We were all expected to bring enough dry rations to cook and feed families - 700 people every day.

Nandita Sen, Schoolgirl, Calcutta. August 1945

(Source: Nandita's story at: http://timewitnesses.org/english/%7Enandita.html, Nandita Sen Hyderabad - January 2005, seen 18th November 2005)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Nandita Sen)

Famine Relief in Behala

Even before the R.A.F, had gone, this wide open space by the road, which Father D. had cleared from the jungle 'nearly forty years before, was needed for something else. A terrible famine was raging in Bengal in the summer and autumn of 1943. The Provincial Government seemed helpless; indeed, ugly stories were told of fortunes made by people in official positions who hoarded rice. The hungry villagers struggled into the great city: there at any rate they thought that they would be sure to find food; but thousands died of starvation. As in the days of the plague in London, carts had to be sent round the streets to collect the dead.

Some at least were saved when they reached Behala on their way to Calcutta. With the help of gifts from the Friends' Ambulance Unit and some generous friends, Douglass was able to feed two hundred women and children every morning for two months. Then Lord Wavell, the Viceroy, took over the work of relief in Bengal over the heads of the useless Government. He set the Army to work, and soon lorries were rolling along the roads labelled 'Food for the People'. The Army requisitioned most of the remaining part of the compound for the purpose of making great food dumps, and all day long lorries, loaded with sacks of barley flour (for rice could no longer be got), roared in and out till the Rains of 1944 made it impossible to keep grain in the open any longer.

The shrinking of space for the school and the huge rise in the cost of food meant that Father D. now had fewer boys under his care and it became necessary to scrutinize all expenditure very carefully. The old Father could not abide the voluminous forms which flooded his table when rationing came in, and they all went into the wastepaper basket. He had come to India in an age when a sahib was a sahib, and he simply refused to fill up any forms—and no inspector was bold enough to insist that he should.

Friends of Father Douglass, Missionaries and Charity workers in Behala, Calcutta, 1943.

(Source: Father Douglas of Behala. London, 1952 / Reproduced by courtesy of Oxford University Press)

Inch by Inch

For the first time a U.S.

religious organization has been permitted to send food to the Bengal famine victims (TIME, Nov.1). The

U.S. Government last week told the American

Friends Service Committee that it may ship to India some 20,000 cases of

evaporated milk (value: $100,000) to be

distributed cooperatively by Hindu, Mohammedan and Christian agencies.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Dec. 6, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Drama in

Atlantic City

Into Atlantic City's

Claridge Hotel stalked trouble for the United Nations' brand-new Relief & Rehabilitation Administration.

For days India's official

delegate, mild Sir Girja Bajpai, had never dared bring up the bitter question of India's right to petition

UNRRA for desperately needed food in time of

famine. Sir Girja knew that in Bengal this week there was no celebration

of the bumper Aman crop (the December

rice crop). There was no celebration, only desolation, and silent villages ravaged mercilessly by hunger and

disease. For there was no one left to harvest

the Aman crop—the stricken peasants sat on doorsteps mourning their dead

families, too tired, too sick to take

courage from the ripening paddy fields.

But J. J. Singh,

president of the India League of America, moved into Atlantic City, called his own press conference, and forced

the question into the open. Let UNRRA rush

food to India at once.

Chairman Dean Acheson and

British Colonel John J. Llewellin demurred. UNRRA relief, said they, was only for areas liberated from the

enemy. Bluntly retorted Interloper Singh: If

relief is for war victims, how can the United Nations refuse aid to

famine-stricken India, where war has

stopped all rice imports from Burma?*The big nations, embarrassed but adamant, refused to reconsider.

New Dissension. But the

big nation delegates could not succeed in shushing down small or poor nations on all questions (each

participating Government has an enual vote). When the U.S. and Britain proposed that UNRRA relief be given free to

postwar Germany if she was unable to

pay, the small nations rose in storm. With a violent and tumultuous "no"

they voted down the proposal. Said

they: Germany must pay for all the relief it gets.

Thus, even before Dec. 1,

when the Council expected to close its first conference, Director General Herbert Lehman's vast job

was smashing into snags.

It could hardly be

otherwise. Delegates from 44 nations had sat down at a green baize-covered table to work out a democratic

formula for relief to war-torn countries

containing 500 million people, where human wreckage is on a scale almost

too huge to conceive.

After three drudging

weeks, and in spite of squabblings, most major policies and procedures had been argued over, fought

over—and mostly solved: > Director General Lehman had won his right to allocate materials to countries most in

need, regardless of their ability or

inability to pay.

> Relief would be of

two kinds: immediate necessities to sustain life,and seeds and equipment to restore economic independence.

>The cost would be $2

billion, paid for by a contribution from each country (where possible) of 1% of its national income.

New Dimension. And yet,

as one by one the delegates from occupied countries described the monstrous desolation that would face them on

the day of liberation, conferees breathed in

a sense of urgency, and the conference took on a new dimension. Slowly

UNRRA plotted the first task of peace.

If it succeeds, it will do more than bring relief to destitute peoples: it will prove that the United

Nations can create a workable machinery of

international cooperation.

At least one thing was

clear. The total estimated $1 to $1.5 billion cost to the U.S. was approximately half what U.S.

citizens paid out in

relief through Herbert Hoover's committee after World War I.

This time, others were

sharing the burden.

The invaded countries

asked for rehabilitation only to help them stand on their own feet—and they would pay to the limit of

their ability.

*For news of U.S. relief

to India, see p. 45

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Dec. 6, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Azad Hind Government offers Japanese rice for Bengal

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

November 1943 - Food rationing in Calcutta

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Wavell and the Golden Throne

At New Delhi last week, Viscount Wavell of Cyrenaica and Winchester took

office as India's 19th Viceroy. The ceremony was as simple as Lord Wavell's

brisk arrival by plane, as austere as the task he now faces.

Not till the viceregal flag broke out over the palace dome was the public

aware that Field Marshal Lord Wavell had mounted the golden throne. Within

jasper-columned Durbar Hall, he had taken the three great oaths: 1) the oath of

allegiance to King-Emperor George VI; 2) the oath as Governor-General of British

India; 3) the oath of Viceroy representing the Crown to the autonomous Indian

States. In that nine-minute ceremony, he had also attained a sumptuous

$10,000,000 palace; a job paying in salary and expenses about $280,000 a year;

the top appointive post in all the British Empire's glittering hierarchy;

direct power unrivaled by any king on earth, rivaled only by a few dictators;

and a set of administrative burdens in scale with his viceregal grandeur.

The Bellies. Heaviest of the burdens was the oldest one—the weight of

India's 390,000,000 Moslems and Hindus of many castes, divided amongst

themselves, in chronic ferment against the British Raj and all that the Viceroy

represents. Lord Wavell had followed monolithic Lord Linlithgow, the outgoing

and unregretted 18th Viceroy, into office at a time when the Raj was at its

lowest point yet in both Indian and British esteem. Many of India's millions, ordinarily unstirred by and unaware of the

political issues which engross the articulate minority, felt in their bellies a

failure of the Raj. They were starving.

Famine gripped large areas of India

(TIME, Oct. 18). Three days after his inauguration, Field Marshal Lord Wavell

announced that he would visit hunger-plagued Calcutta, where whole families were

dying on the streets. The Bengal Government was one of several provincial

Governments which had dallied at commandeering rice crops and stocks, and

distributing them to the hungry. Lord Wavell has the power to do so for all of

India, and the Central Government has already threatened to override dilatory

provincial authorities if necessary. But, even with the utmost vigor on his

part, a solution will be difficult.

Cure and Spot. Last month Lord Wavell announced in England a three-point

India policy. The points, in the order of importance and timing which he

assigned them, were: 1) the organization of India for the complete defeat of

Japan; 2) the raising of social standards throughout India; 3) the gradual

transfer of political power to Indian hands.

Lord Wavell's bluntness in putting Indian independence last on the list

showed no desire to placate anyone. It did show a realistic approach to the

fact that India is an important Allied military base as well as a shaky pillar

of Empire. But the same bluntness was bound to alienate many Indians before he

had mounted the throne. Indians could—and did—point out that a starving India

could be neither an efficient base nor a willing ally. With no real evidence as

yet, they were already branding him as another imperialist whipping master. And

many Britons at home, horrified at the failure of the Raj to control the

famine, were loud-voiced for the release of the Congress leaders jailed by

Linlithgow, the removal of Indian Secretary Leopold Amery.

The hero of Cyrenaica had been in some tough spots, had won triumphs and

survived reverses in Africa and Greece. On the golden throne of the Viceroy, he

was in the toughest spot in all the Empire.

The Imponderable Mr. Bose

In Singapore last week a

"provisional government of India" was set up by the Japanese. Its

chief: Subhas Chandra Bose, ex-President of the Indian National Congress. Its

first intention to declare war on Britain and the U.S.

Cherub-faced lady-killer Bose has

long been a friend to the Axis. In 1941, faced with prosecution by the British,

he fled India, later cropped up wining & dining with Axis leaders in Berlin

and Tokyo, plumped for Fascism. Broadcasting to discontented India over Axis

frequencies, Bose once said: "... In December 1941... but one cry arose from

the lips of the brave soldiers of Nippon: 'On to Singapore!' Comrades, let your

battle cry be 'On to Delhi!"

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Nov. 1, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Disposal of the dead

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

The dead heaped around Government House

I remember going one day in my car, probably on a Red Cross mission.

And I happened to be going past Government House on this occasion.

And to my horror there were hundreds of dead bodies, which were quite deliberately laid out against the railing; as a form of protest.

And it was tremendous shock to one’s system.

I don’t even think that everyone was dead; they were in the throes of starvation.

When I saw all those dead and dying laid all around the railings of government house.

It was a horrific sight…

Everywhere there was starvation evident.

Sheila Chapman-Mortimer, Calcutta Red Cross Volunteer and wife of the head of Bengal chamber of commerce, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

The famine was on in Calcutta at that time

When

Montgomery went to Italy we were posted to India. This mean going back to Suez to

get on a transport ship, this time a cargo ship, to Bombay, and a train to Calcutta. The famine was on in Calcutta at that time, it

was a terrible sight to see all these starving people. We used to go round in

the morning picking up those who had died overnight.

Fred Harris, Royal Air Force, Calcutta, 1943

(source: A2752427 Abroad With The Royal Air Force Edited at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

A city suffering a famine

Calcutta

was an overpopulated city suffering a famine — dustcarts collected bodies of

those who had died during the night - the humidity, smell and dirt was

overpowering.

Leslie Brazier, Royal Air Force, Calcutta, 1943

(source: A3935432 War Service Abroad as a Wireless Operator at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

The river was was just unbelievebly full of floating bodies

[…]

on the trip in question the river was just unbelievebly full of floating bodies

and it was horrendous.However when I came on to the bridge I did ask the pilot

for the reason and he put it down to a rice famine that they had had in Bengal

and then added a classic ending by informing me that you could always tell what

sex they were by which side of their body they were floating on.

W.C.B.Gilhespy,Officer

Merchant Navy , Calcutta, 1943

(source: A2152379 World War Two: Memories of the Merchant Navy Edited at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

and off they would go with the body swinging in between them

[…]

Calcutta is a very big place with a very large population of about seven

million, and because of the advancing Japanese Forces towards Eastern Bengal

there was a kind of exodus from the eastern Towns.

At

night time it was almost impossible to walk along the pavement of Chowringee

(Calcutta’s main Street) because of the thousands of half starved evacuees that

were laying in every available space that could be found, and in the morning

the sick and the dying, and the dead would still be there covered with flies.

Then the death squad would come along to pick up the dead bodies. They would

tie the hands and feet of the dead, then put a bamboo pole between the feet and

the hands, hoist the pole up on to their shoulders, and off they would go with

the body swinging in between them. They would go to meet a bullock cart, and

pile the bodies up on it. This was a hell of an experience for us, it was

something that we had to adjust to.

Stan Martin, soldier, Calcutta,

early 1940s

(source: A1982955 Stan Martin's WW2 story at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Army relief work

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

From Viceroy Wavell’s diary

I found things much as I had expected from what I had read and heard - widespread distress and suffering, not as gruesome as the Congress papers would make out, but grim enough to make official complacency surprising; I don't think anyone really knows the whole situation or what is going on in some of the outlying areas, but obviously we have to get to grips or it may get out of hand altogether. I saw all the Ministers yesterday evening, told them they must get the destitutes out of Calcutta into camps which should have been done long ago, got them to accept a Major-General and staff to help with the transport of supplies and the assistance of the Army generally. (Diary, 29 October 1943)

Filed-Marshall Lord Wavell, Viceroy of India, 29 October1943

(source: page 105 of Trevor Royle: “The Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

At the barracks gate

That summer, July August, we had orders not to waste any food at all.

Whatever was left over had to be distributed.

There where probably hundreds of villagers, babies in arms, old men…

They would sit there night and day, just waiting for food.

The guard was controlling the perimeter of the camp and the sick people and bodies where cleared away in the morning.

But one morning, the guard came back with the report that a girl, not dead, had been attacked by jackals, and part of her arm had been torn, eaten off.

They where visibly upset; hardened troops when they saw things like this.

We had never experienced starvation nothing like this.

In India wherever we went at the time we would always find beggars,

but this was different, this was starvation.

This was a famine in the true sense of the word

There was no food at all and we tried to feed them.

Sgt John Crout, Royal Artillery, Summer 1943

(Source TV Programme ????)

… a couple o' cans o' bully beef from our ration wasnae goin' tae help them

Then there was the Bengal Famine- I was there at that time. I remember goin' round and pickin' up old people and babies—dead bodies, you know—and takin' them to burial places, goin' round wi' lorries collecting corpses- We should have been goin' round wi' food for them and medical supplies. But mere was a war on, I suppose—tills was the old story. They cut our rations at that time. This was our contribution. But I mean that was no use because their diet was entirely different from ours. So cuttin' out a couple o' cans o' bully beef from our ration wasnae goin' tae help them. Because a lot o' the sects in India don't eat beef anyway. Other ones don't eat pork. I don't know which ones is which. The cow's holy to the Hindus, I think it is. Well, the Bengal Famine was a pretty distressing experience for us. Well, we were all young guys. We had never seen anything like it in our lives. We were really shocked. Apparently there was thousands died, I saw dozens and dozens anyway, I had to handle the bodies and carcases—the old and the young. They were the most susceptible, of course.

Eddie Mathieson, Marines’ commando soldier on the Burma Front. Calcutta, 1944/45

(source: page 236 of MacDougall, Ian: Voices from War and some Labour Struggles; Personal Recollections of War in our Century by Scottish Men and Women. Edinburgh: Mercat Press, 1995)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ian MacDougall)

lest anyone should die on our post

The next posting was to the Midnapore area, which had suffered a typhoon 12 months earlier and was now seeing much starvation and death. Supplying the Indians with food had to be carefully handled lest anyone should die on our post and we became responsible for their burial.

Douglas Gibson, Royal Air Force

wireless operator, Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4175237 Grandpas War at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

December 1943 - The famine comes to an end

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

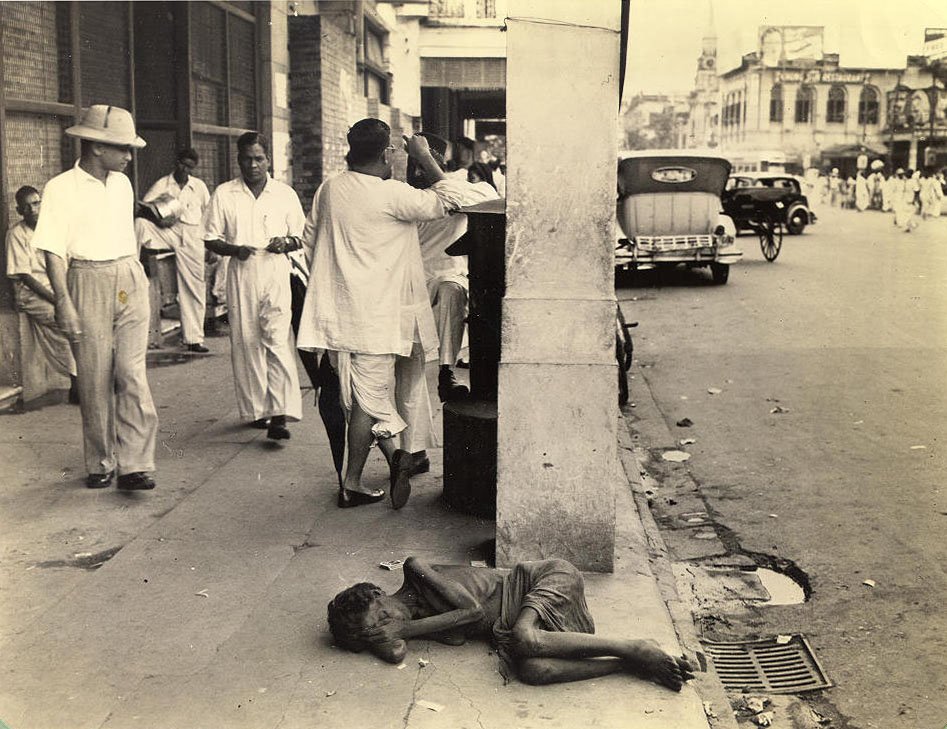

Downton Calcutta street scene

The indifference of the passer-by on this downtown Calcutta street to the plight of the dying woman in the foreground is considered commonplace. During the famine of 1943, cases like this were to be seen in most every block, and though less frequent now, the hardened public reaction seems to have endured.

Clyde Waddell, US military man, personal press

photographer of Lord Louis Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix

magazine. Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source: webpage http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 /

Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson, South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt

Library, University of Pennsylvania)

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Death in Bloom

Said Food Secretary R. H. Hutchings: "Bengal now has ample food. . . ." Added Calcutta officials: "Famine mortality is now down to 30 per day." By last week it was beyond dispute that Viceroy Wavell had done a good eleventh-hour job on an almost hopelessly bungled situation. He had brought an old soldier's efficiency to bear in the distribution of foods among the starving.

Now disease was on the march. In famine-weakened Bengal malaria was taking a death toll comparable to the famine's fabulous 40,000 a week of early November. Cholera, dysentery and dropsy were also in murderous full bloom.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Dec. 27, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

While the Paddy Ripens

In the paddy fields of Bengal, the December rice crop is lush and full. But while it swells, the stricken Bengal peasant sits mutely on his doorstep. He is too benumbed by famine to reap the paddy.

In Bengal's capital, Calcutta, thousands are still dying of hunger. Grim, hardworking men of Auchinleck's Army, aided by official and private agencies, belatedly distribute what food they can get. It does not add up to much—half a pound of grain per mouth per day. Many thousands of Indians, because of debility and disease, are beyond such help. But last week an improvement was noticed: famine deaths in Calcutta had fallen from over 200 to about 100 daily.

Unless the December paddy is harvested, the improvement will be only temporary. Spokesmen for the Army and the British Central Government are aware of this fact. But, caught in an intra-government maze of both British and Indian making, they feel that they should help with the harvest only if they are asked. So far, the Bengal Provincial Government has not asked. The life-giving paddy ripens—and waits.

(source: TIME Magazine, New York, Dec. 13, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

New Lamps for Old

[…]

Riots & famine. The

new government faced […] pressing problems. In Bengal and Madras provinces, acute food shortages

threatened to produce isolated pockets of

starvation, while Moslem outbreaks (minor but persistent) and

strike-crippled rail system threatened

to paralyze transportation. Last week, even the hope' of aid from abroad

was deferred: the U.S. shipping strike

(see NATIONAL AFFAIRS) had tied up 225,000 tons of wheat; Siam failed to deliver any of its promised rice shipments;

Indonesia delivered but a few thousand

tons of the promised 700,000 tons of paddy (unmilled rice).

Indian leaders sadly admitted the difficulties. Said External Affairs

Minister Jawaharlal Nehru: "What are we aiming at? Freedom? Yes. Higher

standards? Yes. But we are ultimately aiming at feeding, clothing, housing,

educating and providing better health conditions for 400,000,000."

[…]

(source: TIME Magazine,

New York, Sep.

30, 1946)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Now the Pale Horse

Lest the amply fed think that India's immense misery had passed, an

American missionary wrote home a

letter: "It will take at least five years to recover from the effects [of

1943's famine] from a health standpoint, and more than that to recover from a

moral standpoint. . . . The poor have

sold off their goats, chickens, cattle, brass vessels, ornaments, and the like in the past hard

year and are far less well prepared to meet the exigencies of another such year. . . ."

For the moment the rice would go around. Bengal's harvest had been good,

Viceroy Lord Wavell's speed-up of food

transport effective, foreign charity helpful. But all this was amelioration, not solution. The blown and

shriveled masses who had not starved to death

in the famine areas of northeastern India were scourged now by

pestilence, by cholera, dysentery,

malaria, dropsy, pneumonia. The famine had sharpened India's old and

limitless needs: more rice, in steady

supply; milk for her children; medicines for her sick; shelter for her homeless. Without these,

thus far merely trickling in, there would be

many added to the multitude of dead.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Feb.

21, 1944)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

"Did you still see after effects of the Bengal Famine of 1943?'

No. We arrived in India, landing at Bombay sometime in June 1944, travelled by train across to Calcutta, then up to Gushkara arriving there in early July 1944. I wasn't even aware of the Bengal famine of 1943. There was no evidence of it out there in the rural region where we were located at that moment. I recall no evidence of food shortages among the local people. They seemed well fed and happy.

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley)

Still Starving

It

was wonderful to return to Bakloh and we were given a very pleasant but all too

short leave before returning to Calcutta and a plane back to Burma.

In

Calcutta, people were dying in the streets from starvation.

Arthur Gilbert, Army, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A5011336 Going to War on the Tube - Chapter 6 Mandalay to Rangoon at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1943-44 – The Famine Inquiry Commission

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

Divided views on the famine

For example, we were by no means in love with the war hero Churchill. Now that their correspondence is declassified we learn that our view on Churchill's stand on the Bengal famine was shared by Wavell, the Viceroy at the time, and also the future Viceroy, Mountbatten.

Nandita Sen, Schoolgirl, Calcutta. August 1945

(Source: Nandita's story at: http://timewitnesses.org/english/%7Enandita.html, Nandita Sen Hyderabad - January 2005, seen 18th November 2005)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Nandita Sen)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home ● Sitemap ● Reference ● Last updated: 11-March-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org