The unstoppable Japanese

Advance

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

● Sitemap ●

Reference ●

Last

updated: 19-May-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

At first even the Pacific war had

seem far away, with the fall of Hong Kong sad but not too unexpected. In the

early months of 1942 this all changed. In short succession the Japanese managed

to overrun the European possessions in South-East Asia. The fall of the

fortress city of Singapore was great shock and in less than a month Rangoon

also had fallen, and by the end of March the Japanese had reached India near

Chittagong and the on the Andamans.

Would Calcutta be next? Would there

be a panic; would the British and their allies fight; would the independence

movement welcome the Japanese?

In the meantime there were many

refugees from Burma with horrific tales to tell, many relatives were trapped,

missing or killed behind enemy lines and in the city itself some fifth

columnists working for the Axis.

Calcutta had suddenly found itself

on the front line facing the march of a seemingly unstoppable enemy.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

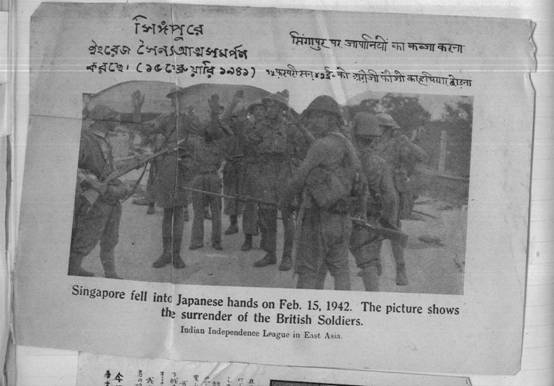

15

February 1942 - The Fall of Singapore

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

Japanese Leaflet

collected by Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart, I.C.S. (Indian Civil Service), Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005 /

Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

Ron and I stopped to speak to

two of the boys

Earlier in the year, before the fall of Singapore, an English regiment arrived. The men were put in tents on the Barrackpore Golf Course. The following day when walking past, Ron and I stopped to speak to two of the boys. They had almost been eaten alive by mosquitoes – their poor legs were inflamed and covered by blisters. We invited them to come along to our house, which they did and were exceedingly grateful for the hot bath, a good meal and having their legs dressed. We did not see them again as they had all left for what turned out to be Singapore where they arrived in time for the fall of the town and the humiliating surrender to the Japanese.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Barrackpore, 1941

(source:page 92 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

Lectures organized by the St

John’s Ambulance Corps.

In our district many of the women, including me, attended lectures organized by the St John’s Ambulance Corps. Later we were examined by the Military Doctor. Like all those who passed, I was very pleased to receive my certificate.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, early 1942

(source:page 92 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

Soldiers’ Club was formed in

one of the old houses in Barrackpore

A Soldiers’ Club was formed in one of the old houses in Barrackpore. Groups of some six or more ladies from the various compounds attended in turn each night for voluntary work there. Tea and cool lime drinks were provided free and for a few annas; sandwiches, cookies, fish and chips were offered to the men. It was quite hard work for us especially during the hot season, but much appreciated by the soldiers who flocked to the club in large numbers.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Barrackpore, 1941

(source:page 92 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

The Bengal Ladies’ Artillery

Not least important was the newly formed contingent of women willing to fight the enemy if need be. I do not know whose mighty brain produced this child and named it the Bengal Ladies’ Artillery but a large number of women responded to the call with great enthusiasm - and I was one of them.

We were measured for khaki trousers and shirts to match and ordered to wear topis which was not in accordance with the Military Doctor who in his lectures told us that topis were no longer necessary as there was no such thing s sunstroke, but heatstroke, a statement soon to be confirmed with the arrival of the American soldiers who wore no topis.

Twice weekly transport was provided by the military to take us to and from the parade ground in Barrackpore. A young and rather bold sergeant-major taught us drill and wasn’t sparing in his comments on our behaviour and deportment. W had to learn how to use a rifle. The Lewis gun also came into the picture and there it wasn’t just sufficient to know the usage, but to be able to dismantle and assemble it within a give time. Not being mechanically minded I was astonished at the ability so many of the girls possessed and with what amazing speed each piece was named as it was placed in proper order. There was no hope for my competing with such efficiency, but I did redeem myself a little on the range where by some miracle I was lucky enough to score a higher count than most of them.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Barrackpore, 1942

(source:pages 92-93 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

Calcutta was full of soldiers

Calcutta was full of soldiers and army trucks went up and down all day long.

Dum Dum airport in 1942-46 was one of the busiest airports in the world.

Katyun Randhawa, a young Indian (Parsi) girl, Calcutta, 1942-3

(source: A5756150 The bombing of Calcutta by the Japanese Edited at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Gas Mask Drill at the

Kindergarten

We were all issued with little shouder bags that contained a gas mask, a large square rubber to place in the mouth (to absorb shock), a square bicycle lamp, a first-aid tin box, a pencil and notepad, some ointments in tubes and a tiny bottle of smelling salts.... oh and a football ref's whistle.

We had drill practise following assembly. We had to learn how to breath in the masks while running and jumping about: not as easy as it looks because we kept 'misting up' and smashing into one another. We really enjoyed squeezing ointments onto one another and taking sniffs of the smelling salts. If you sniffed to hard your eyes nearly shot out of their sockets and there were enough tear drops to make a few cups of tea.

Ron M. Walker, 7 year old boy, Calcutta, 1942-3

(source: A2780534 My Wartime Childhood in Calcutta, India at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

March

1942 - The Fall of the Dutch Eat Indies

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

New Pacific

The world and World War II

changed last week. By their conquest of Java, the Japanese split the far Pacific.

Its vast expanses ceased to exist as a single Allied war area. The great zone

of strategy, action and command became a set of separated zones. Inevitably, in

advance of Java's fall, the Allies dissolved the unified system of command

which they had established to direct the far Pacific war from Java. General Sir

Archibald Wavell, the Supreme Commander, flew in a U.S. plane from Java to

Ceylon, then to India and Burma, then into China, then back to India. Like

writing on a wall, his travels traced the perils which the U.S., Great Britain

and their allies must now face, the changes which they must deal with and

somehow use for victory.

Wavell for India. Of all

the new zones of war, India was suddenly paramount. As a central Allied base

for supplies and offensive action, it loomed even above remote Australia (see

p. 21). To hold India, to bring its masses into the war, Britain must pay a

price, both politically (see ,p. 26) and militarily. General Wavell, therefore,

was taking no back seat when he resumed his command of India's (and Burma's)

forces.

The Allies had to write

off southern Burma (see p. 20). General Wavell now had to prepare the defenses

of India proper. Defending India, he also defends China and its last supply

routes. He defends Russia on India's north. He defends Suez and the Middle East

from an east-west Nazi-Japanese pincer. Above all, for the final phase of World

War II, he defends in India a necessary Allied supply center and base for

future offensive action through China.

Ceylon for Wavell. At the

southern nub of India, where the Indian Ocean meets the Bay of Bengal and the

Arabian Sea, lies a focal center of General Wavell's task: Britain's island of

Ceylon.

Holding Ceylon, Wavell

holds the sea entrances to India's eastern ports (Madras and Calcutta) which

are also inlets for China's supplies. On Ceylon is Trincomalee, Britain's

secondary naval base, immensely important now that Singapore is gone.

Trincomalee is now the Allies' only useful naval base north of Capetown and east

of Suez. Whoever holds Trincomalee and Ceylon's airdromes holds the key to the

Indian Ocean and all its vital sea routes between Africa, Australia, India and

the Middle East. Without Trincomalee and Ceylon, the Japanese can make Allied

transport in the Indian Ocean dangerous and expensive. With Ceylon, they could

make it almost impossible.

Last week, when the Japs

bombed the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, they were softening up a way

station on the invasion road to Ceylon. And Ceylon, just 60 miles off southern

India, is a way to invasion of India itself. It could even be a substitute for

invasion. With eastern India bottled up, with ships and planes in position on

Ceylon to raid even the Indian routes to the vital ports of Bombay and Karachi on

the Arabian Sea, Japan could well let India soften and crumble under blockade.

Chiang for China. When

General Wavell landed at Lashio in China, he did not receive Generalissimo

Chiang Kaishek. The Generalissimo received Wavell. The meeting was a seal upon

China's final admission to full estate among the Allies. It was also a belated

recognition that China may yet be the only front for a direct land and air

assault on Japan, that planes and tanks and heavy artillery for China may yet

make the difference between victory and defeat in the Far East.

Australians for Australia.

Simply by omitting Australia from his prodigious swing, General Wavell accented

that menaced Dominion's status as an important and lonely zone. Even as the

unified Command was dissolving, Australians complained that it had never been

wholly unified or wholly effective. They took command of Australia for

themselves, with their tough, hard-talking, fast-moving Lieut. General Sir Iven

Mackay at the top. No sooner had they done so than the Jap appeared on the

horizon (see p. 21).

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Mar. 16, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Oil Can Lose the War

Allied experts who once

boasted that oil would win the war began to realize last week that the oil may

get into the wrong hands. It was a rude awakening.Before Pearl Harbor the U.S.

and Britain's fleets drew on the vast oil fields of the Western Hemisphere.

Soviet Russia and the Armies of the Middle East had Baku and Batum. Australia,

Hong Kong and Singapore were next door to the Dutch East Indies. The anti-Axis

powers of the world controlled 97.5% of world production. It was as simple as

that.

But the Japanese have

closed the United Nations' filling station in the far Pacific. Adolf Hitler, if

he drives into the Middle East, may capture Baku and Batum. Then the Axis would

not only have oil enough for its war machine (after destroyed mills and refineries

are repaired), but would force the United Nations into complete dependence on

the Western Hemisphere.

Oil there is in the

Western Hemisphere aplenty: last year's production was 1,761,951,000 barrels,

78% of world production. But nearly 7,000 miles of water -a four months' round

trip for a fast tanker -lie between San Francisco and Melbourne. India's port

of Calcutta is 16,425 miles from San Francisco. It is 4,673 miles from New York

to Archangel. And all these trips will require some convoying.

Last week the Navy

Department's count of tankers lost in the western Atlantic since Dec. 7 reached

17, an average of six a month. Although tanker production during 1941 was only

15 ships, 1942-43 calls for 215 new vessels, an average of 18 a month. But even

these promising figures could not overcome the chill fact that the onetime

Allied trump card, oil, was no longer a trump. The submarines that smacked

shells at the refineries of Aruba and California were probing for vital or

gans, for these refineries produce high-octane aviation gasoline, of which the

hemisphere has none too much. Grumped the New York Herald Tribune's old

Columnist Mark Sullivan: "It is by far the greatest problem of

transportation and supply -what experts call 'logistics' -ever faced by any

nation at war."

(source: TIME Magazine, New York,

Mar. 16, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories of 1940s

Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

08

March 1942 - The Fall of Rangoon

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

Japanese Burma

collected by Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart, I.C.S. (Indian Civil Service), Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005 /

Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Chink in Armour

INDIA will long remember gratefully the visit of Marshal Chiang Kai-shek and his wife. They came at a critical hour in the history of India and China and their visit will itself help to make the future history of both countries. The Generalissimo has sought information which is vital. He must have wished to know what is the position in China's rear. Japan has turned her flank and both by land and sea has made a threatening advance in her rear. The importance for China of Burma needs no emphasizing and now there can be few who do not see the importance of India and also the danger to India herself.

To know where India stands, how solid she is in support and, if not solid, how she can become so, what potentiality and resources she can be counted on to develop and contribute, what is the country's morale—all this information is vital for China. To discover or uncover the truth the Marshal has to confer not only with the civil and military authorities but also with the representatives of parties and with people in different walks of life. His inspiring farewell message and Madame Chiang Kai-shek's address at Santiniketan show that they made good use of their time. They are not satis6ed with what they found. '

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, February 23, 1942.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Bitter

Blow

The Burma Road was cut. Japanese dominance in the Bay of Bengal left

India's naked eastern coast exposed to attack from the sea. Rangoon was on

fire. Reinforcements now would be too late.

On the muddy Sittang River flats, east of the Burma Road and a scant 60

miles north of Rangoon, the outnumbered defenders fought on bravely under

General Sir Alan Fleming Hartley. A north-south British Imperial line west of the

Sittang held under repeated Japanese assaults. Fresh divisions of tough Chinese

troops were reported on the way down the Burma Road.

Toward Rangoon. The Jap had not reached Burma first, but he did have the

mostest men. When the fiercely fighting, outnumbered defenders succeeded at

times in stopping his slow push toward Rangoon, he simply slackened his fire,

tightened his lines and waited for reinforcements from occupied Siam. When

Allied fighter planes, notably those manned by American Volunteer Group pilots,

scored heavily against him aloft, he prudently lessened his aerial activity.

His lightly clad, lightly armed soldiers advanced through dense jungles and

across three rivers. Additional reinforcements had been released by Singapore's

fall for the thrust at Rangoon.

An American pilot, after visiting four large Burma towns, told U.P.

Correspondent Karl Eskelund that many Burmese had sold out to the invader. His

report: "Natives in many districts have rebelled and are killing unarmed

Britishers. The Burmese are assisting the advancing Japanese in every possible

way. . . . Rangoon is a horrible place. Foreigners risk their lives when they

walk in the city, which is completely in the hands of looters and killers who

are running amok."

Death of a City. Rangoon presented a sorry picture. Evacuation of the

city continued, thousands of refugees streaming out along two roads to northern

India. Authorities dealt summarily with looters and "incendiarists."

but the situation appeared well out of hand. This time the scorched-earth

policy was really being applied: wharves, mills, storage tanks, vast supplies

of rice, a wealth of U.S. material destined for China were in flames. Because

there was no time to assemble them. 100 General Motors trucks, which had been

destined for service with Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek, were destroyed. The

conquerors of once-beautiful Rangoon would find a looted, smoking city.

And it was not likely that the Japanese would do much, at first, about

rehabilitating and repairing Rangoon. Their task was to consolidate their gains

in southern Burma, to control the Indian Ocean, to see to it that China's

supply lines were neither reopened nor revised. Two bombing attacks on Port

Blair, capital city of the Andaman Islands, famed Indian penal colony and

weather observatory sites in the Bay of Bengal, served notice as to which job

the Japanese will tackle first.

With these islands as aerial and naval bases, they would be within

bombing dis tance of Calcutta and Chittagong, Indian ports for the new highway

linking Assam Province in India to Sikang in China.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Mar. 9, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

The Flames of Toungoo

Rangoon was a grave. The

roads of southern Burma were alive with miserable Indian thousands, in flight both from the Japanese

and from long-knived Burmese nationalists. To

every white man they saw, the Indians lifted dark hands, dark faces, and

cried "Sahib! Sahib!" They

cried for water, for money, for safety from the lurking dacoits who knifed and stripped the stragglers.

They cried in vain. The

white men also were in flight from southern Burma. Some stayed in Rangoon, to shoot Burmese looters and hold to

the last, until the Japs finally entered

this week, the remnants of that golden city. British and Indian troops

fought, fell back, fought again. British

crews arrived with a few U.S. tanks-too few. U.S. pilots in China's American Volunteer Group had to abandon

Rangoon, after taking a heavy toll of Japanese

planes with the few bullet-battered fighters left to them. Correspondent

Leland Stowe watched a bombed village burn,

and wrote "When you looked again at the sagging skeletons of these wooden structures, somehow you

thought immediately of Japan-Japanese buildings

are made of the same tinderlike material as these Burmese dwellings.

That seemed to be what the flames in

Toungoo were saying."

Over the Mountains.

Southern Burma was all but gone. General Sir Archibald Wavell, taking over the India-Burma command (see p. 19), had

to assume that it was gone. He had then to

decide what more to defend for the salvation of India.

The immediate answer was:

northern Burma. Its formidable mountain masses along the India border would slow if not halt the penetrative

Japanese. Mongols, invading India seven

centuries ago, had shied off from those ranges and chosen to enter by

easier routes from the northwest. But

north Burma had one immense value which compelled its defense to the utmost. Through mountains to the north the

Chinese were boring a new truck route to

China, to replace the lost Burma Road. A regular air-freight route over

the same mountains was also in prospect.

Through a few high and difficult passes (see map), elephant trains had already borne some

supplies to river and highway inlets into China.

It was almost certain

that the Japanese would drive on northward, do their most to block these lifelines. With the same stroke, they

would further brace themselves for a

sea-and-air drive across the Bay of Bengal at India. The Allies, with

all Burma gone, would find it harder

than ever to defend uncertain India, harder still to place bombers, tanks and artillery in China to answer the

flames of Toungoo.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Mar. 16, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Land of Three Rivers

Singapore gave Malaya

meaning; nearly everyone knew that Singapore was a great naval base. Burma had no Singapore. Burma was a

strange place, with strange names, where

Japanese invaded, British retreated, and young Americans flew gallantly

in the alien sky. Last week, as the

battle for Burma ran its course, it was still a remote, uncomprehended struggle to most of the world.

Burma is a land of three

rivers: the long, motherly Irrawaddy in the west ; the tired, gentle Sittang in the center; the wild

Salween in the east. They rise in the northern

hills, where God lives. They all run southward, through Upper Burma to the

rice fields of the south, and then into

the Gulf of Martaban and the Bay of Bengal.

Who conquers Burma must

win the rivers and their valleys. With them go Burma's chief port, Rangoon; the oil of Yanangyaung, on the

Irrawaddy ; the ruby and silver mines; 85%

of all the precious tungsten in the British Empire; Burma's rubber plantations;

the inland cities—Pegu, Prome,

Mandalay—where Burmese kings once ruled their separate realms, and the British were never quite at home.

Japanese strategy was

first to seize the estuaries. The invaders drove from Siam into extreme Lower Burma, and then around the Gulf

of Martaban to ruined, abandoned Rangoon.

After Rangoon, the battle

for Burma was a struggle to keep the Japs in the south, at the river mouths. In the spring, the south is a

grey, heat-beaten land, where only the rivers

are cool and even the wide rice paddies gape with cracks in the baking

earth. It is a time when prudent men,

fools, even Englishmen stay out of the midday sun. But the Japs fought in the sun, and drove the British

steadily up the Irrawaddy and Sittang valleys.

Then the Chinese came down from the north.

The British and Indians

concentrated on the Irrawaddy front. The Chinese took over the Sittang—and, later, when the Japs opened a

flanking drive along the Salween in the east,

that front as well.

By last week, the Chinese

had pretty well taken over all three fronts. Like the British, they lacked air support and tanks ; they had

to retreat. But one good thing had come out

of the battle for Burma.

After long, bitter weeks

of misunderstanding, Chungking reported that the Chinese had at last reached an understanding with Great

Britain's General Sir Archibald Wavell. King

George conferred the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on

Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek. The

Chinese now feel free to send additional troops into Burma. There they

fight under their own commanders, who

are in turn responsible to Chiang Kai-shek's Chief of Staff, U.S. Lieut. General Joseph W.

Stilwell.

Not Many Men. It was

never a battle of great numbers. The biggest body of British troops reported in the retreat from Rangoon was

1,000, and they had with them all the British

mechanized equipment in Burma. The largest British force reported in

action last week was 7,000. There were

also a few thousand Indian troops, and two or three battalions of native Burmese riflemen, who were the

exceptions to the Burmese natives' general

indifference or hostility. The R.A.F had very little in the air at the

start, practically nothing after a few

weeks of combat. Because the Jap advance threatened the Burma Road to China, Chiang Kai-shek detailed his American

Volunteer Group to Burma's air defense. The

A.V.G. destroyed scores of Jap planes, but lost its own as well. By last

week the A.V.G. was using any old crate

at hand. Finally, the Japanese faced not more than three divisions of Chinese infantry, perhaps 40,000

men.

What Is Left? Southern

Burma is gone. The oilfields around Yenangyaung are gone. The coast whence the Japs can move across the Bay

of Bengal to India is largely gone. But the

Allies still have something to fight for in Burma.

The mere existence of a

fighting force in upper Burma is invaluable to the defense of India. If they have an active enemy in their

rear, the Japanese cannot complacently

advance on India.

Burma is a gateway to

China's roads. If the Japs drive on to Mandalay—they were only 75 miles away early this week—and successfully

entrench themselves in all northern Burma,

they will have a new front on China's borders. But Jap conquest of Burma

is mainly dangerous to the Chinese

because of the great new land routes abuilding from India into China. The Japs choked off the Burma Road

when they won Rangoon; if they win access to

the northern roads, they might all but choke China.

Yet China might still not

be altogether cut off. The U.S. is now equipping a great air-transport line, to fly war goods from

India to China. The Japs were never able to

ground China National Aviation Corp. by air attack. C.N.A.C.'s best

pilots are helping to establish the India-China

service, and they think that it can be maintained and steadily increased, unless the Japanese capture the

bases at both ends.

What Next? Early May

brings the rains to Burma. Southern Burma will be a green, cooled land for the invaders. Its rice paddies will

be lakes, many of its roads will be bogs.

But the best roads will still be usable, for bringing up supplies to the

troops in the north. So will the

Rangoon-Mandalay railroad; so will the rivers, except when they are flooded. In the north, where the fighting is

headed, the monsoon will not halt combat. If

the monsoon has any real military effect, it will be in the Bay of

Bengal. In monsoon time the Bay and its air

are stormy and perilous.

The defenders of India

are doubtless aware by now that nature and geography are uncertain allies. It was once an accepted fact that the

mountainous borderland between Burma and

India was impassable to armies—that the only practical route to India

was by sea and air. Yet refugees from

Burma filtered through those same mountains, 1,000 and more a day. The mountains which overlap eastern Burma and

Siam were also supposed to be well-nigh

impassable. Last week Japanese tanks from Siam wormed through the lower

ranges, in dark prediction of what they

may do on the road to India.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, May. 4, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

“People were making frantic

efforts to get away …”

“People were making frantic efforts to get away … and to get their valuables away. Large numbers of merchants and traders also left, and I was told that the ordinary shop commodities in Calcutta could be bought for next to nothing. That was towards the end of 1941. When I returned to Bengal myself in April, 1942, there was an athmosphere of tenseness and expectancy in Calcutta…. Houses were vacant. Bazaar shops had very largely moved off and a great deal of the population had gone out … [N]obody knew whether by the next cold weather, Calcutta would be in the possession of the Japanese”

LG Pinnell, ICS. Calcutta

April 1942

(source: p. 88. in Paul

Greenough: “Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The famine of 1943-1944”,

New York: Oxford University Press 1982)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Paul Greenough)

far more grumbling in Bengal

than in battered England

Our weakness in the Far Eastern air was still deplorable and this undoubtedly had a bad effect on morale. I had heard far more grumbling in Bengal than in battered England.

Harold Acton, RAF airforce

officer. Calcutta, early 1940s.

(source: page 126 Harold

Acton: More memoirs of an Aesthete. London Methuen, 1970)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Harold Acton)

Evacuating Rangoon

I

was born in Rangoon Burma in the late 30s.

My

earliest memories are of being rushed into underground bomb shelters, with

sirens blaring and hushed voices guiding and soothing everyone, while bombs

exploded with deafening sounds and frightening glares.

My

mother was in hospital having my younger sister, and my father, who worked for

the British Oil Co., was on war duty with the Engineers repairing roads and

railways, to keep the oil and supplies flowing.

Hushed

voices spoke with concern about the birth of my sister, while part of the

hospital was bombed, but 'mother and child were safe'.

My

next memory is of all of us rushing to get on a steamer, leaving everything behind,

all my toys, and then my father, who was carrying me, got off too, and we were

away without him. I held back my tears, gripping my mothers hand tightly,

remembering I had to be brave for my sisters, while I watched the waves on the

side of the ship grow as we progressed from the river to the Indian Ocean.

In

Calcutta we were met by my uncle and stayed with our cousins, with a lot of

fuss, and fun, while we waited for my father to arrive.

It

took him a long time, as he missed all the ships, and came by road, on Lorries

and Jeeps, when the British evacuated.

I

can still feel the relief and joy shared by all the families, when he finally

arrived.

But

he was different, thinner, gaunt, quieter, thoughtful, slower to smile or laugh

and his eyes didn't light up as they used to.

It

took my father some what longer to return to us fully.

Jaidka Family,civilians in Rangoon , Calcutta, 194

(source: A4291157 Early Memories of the War. at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

The Allies in Retreat

I could not have arrived at a more chaotic season. Our small air force in Burma had been decimated; our troops and thousands of civilian refugees were escaping through the jungles and mountains, an agonizing trek of six hundred miles, and the rains were soon expected. Half the Chinese forces had retreated to their own country, the rest were following General Stilwell to India.

Small wonder that I was eyed askance when I reported to P Staff. What the devil was I doing here and what did I think I could do?

Harold Acton, RAF officer. Calcutta, 1942.

(source: page 126-7 Harold

Acton: More memoirs of an Aesthete. London Methuen, 1970)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Harold Acton)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Summer

1942 - The Arrival of the Burma Refugees

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Lest Delhi Forget

Japan is still at India's

door. The R.A.F. sharply reminded India's sahibs and indifferent millions of this fact last week.

A communiqué reported that in 46 days R.A.F.

planes had dropped 100 tons of bombs on Japanese troop and supply

concentrations moving into northern

Burma, near the mountainous but by no means inpregnable,* border of India.

*New Delhi last week

reported that 500,000 Burmese refugees had arrived in India. Some traveled by sea and air, but most of them,

surviving malaria and dysentery, living on

food dropped by R.A.F. planes, found their way over hidden trails from

Burma into Bengal and Assam.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Jul. 20, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

A Refugees Tale

I also saw refugees from Hong Kong and Burma, who lad barely survived their escape.

Of the innumerable accounts I heard of the thousands, mostly women and children, who were trapped in the hills of North Burma by monsoon floods and had to lead 'Robinson Crusoe' lives for three miserable months, I was haunted by that of a fragile girl of Anglo-Chinese stock. Her ivory skin was almost transparent over the childish bones. She had left Moulmein with her parents in December, travelling through Prome, Mandalay, Maymyo to Myitkina, where her father fell dangerously ill. Unable to move, he urged his daughter to start hiking. Her mother stayed behind to look after him.

Though she had been told that the rest of the journey would only take a week, it took over four months. The first lap was comparatively easy, for she joined a troop of fifty evacuees, the road was not too bad, food was obtainable and she got an occasional lift. But soon the road dwindled to a track which was turned into a bog by the incessant rain, and they could only travel a few miles a day. Food became scarce and there was little to buy from the Kachin villages through which they passed. The party split into groups to forage for victuals and every evening when they met again a few were missing, either lost or attacked by dacoits or overcome by fever.

Another couple of girls from Moulmein, sisters aged twenty and eighteen, tried to nurse the fever-stricken: they had charming voices, and they sang to keep up their courage.. These had been joined by four Tommies. Though they were suffering from malaria, the soldiers helped them through the most difficult part of the journey, the ill-famed Seven Streams where many of their companions were drowned. The girls swam naked across the swollen currents and the soldiers followed with their haversacks, containing their scanty clothes and supplies. There were many halts, sometimes of several days. On account of the prevalent fever. Some died of it and were buried in graves one foot deep.

The sisters said prayers

for the dying. Those who could

still walk trudged on through

the grim swamp of the Hukong valley.

Eventually they reached a large camp where they had their first solid meal for a week. Next day the soldiers who had accompanied then collapsed: three died and the fourth was far too weak to move. The sick decided to stay near medical supplies rather than struggle on through the Jungle.

The girls joined a group of thirteen women and children led by a Bengali who claimed to be a doctor. Among them was a boy of fourteen whose parents had died on the road. Twice the party was assaulted and robbed by hill bandits. Leeches fastened on their bare legs as they sank into the mud and they had no matches to bum them off.

The Bengali 'doctor' became a sadistic tyrant. He beat the women with a swagger-cane if they did not jump in obedience to his orders. If they fainted with fatigue he shouted at them them: 'You bitches are holding me back.' And he would thrash them until they got up. He monopolized the rations collected from dumps supplied by our food-dropping aircraft and he compelled the weaker women to submit to him by threats of starvation. The more spirited girls resisted. When he threatened the Anglo-Chinese girl with one of his six revolvers she said: 'Go on then, try it!' But he lost his nerve. However, she got even less to eat for her temerity.

The track grew worse and they had to slither on their bellies through lakes of mud. More often they had to stop from Weakness and exhaustion; even so they managed to cover between Seven and ten miles every day. The farther they tramped the more corpses and skeletons they passed and the 'doctor' robbed them of clothes and whatever money he could find. For a whole month they were detained by floods at a camp of bamboo huts containing five hundred refugees, half of whom died of meningitis within a fortnight. When the water subsided enough to let them continue their trek the girls found Kachin porters to carry them. They were so famished and feverish that they could scarcely remember the last lap of their journey. When they reached the ration dumps at a border camp they were barely alive. The rations were mostly tinned meat which gave them dysentery, after which they were found unconscious on the track by a rescue party organizer by some Assam tea planters. Thanks to these good Samaritans' who had been the first to help hundreds of refugees from Burma, they were carried into India on pack horses. At last they had medical attention, nourishment, and the comfort of clean beds. The Bengali 'doctor's' reputation had preceded him and he was arrested when he reached the India-Assam border. £30,000 worth of rupees had been scuffed in his knapsack, of which £7,500 belonged to the fourteen-year-old boy who had lost his Punjabi parents.

Others corroborated these stories. The ordeal of these refugees struck me as far more gruesome than that of our European fugitives. So much for Rousseau's notion of primitive goodness and the noble savage.

Harold Acton, RAF airforce

officer. Calcutta, early 1940s.

(source: page 112-4 Harold

Acton: More memoirs of an Aesthete. London Methuen, 1970)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Harold Acton)

There was not a day that we

did not read in the ‘Statesman’ of the sad announcement of the death of some

person who had died during that terrible trek

Meanwhile there was the tragic throng of refugees arriving in Calcutta. They had walked across the slippery roads and hills of Burma, stumbling, falling and dying on the way until they reached the safety of Assam where the tea planter welcomed and helped them in every possible way. In Calcutta there was not a day that we did not read in the ‘Statesman’ of the sad announcement of the death of some person - child, a mother or a grandmother – who had died during that terrible trek which claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of civilians.

Eugenie Fraser, wife of a jute mill manager, Calcutta, 1942

(source:page 93 of Eugenie Fraser: “A home by the Hooghly. A jute Wallahs Wife” .Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Eugenie Fraser)

Diary of a treck out of Burma

FEBRUARY

1942

Sunday

22nd

We

(my mother Daphne Johnson and I, Jose)finally left MAWLIAK by Loondwin this

morning. It is a most uncomfortable way of travelling, but no doubt we shall

live through it. The men pole the boats by putting the top of the pole in their

shoulder muscles, and walking the length of the bamboo deck. We stopped at a

place called TACON for the night, about half way to YUWA. It was a terrible

place, as it was just the bank of the river and no flat space for doing

anything.

Monday

23rd

We

left TACON early in the morning; Last night was most uncomfortable as the boatmen

insisted on sleeping on the boats as well. We went along all day stopping for

our meal about 10:30am. We reached YUWA rather late about 5.15.pm. and the

place we stopped at was a buffalo wallow, absolutely filthy, and being near the

village we had a large audience watching us eat our evening meal!! The Phoongis

(Buddhist monks) here presented Mrs. Wheeler with some fresh milk and a bunch

of bananas.

Tuesday

24th

We

left YUWA early. I feel we are really on the way now as we are going up the Yu.

The day passed the same as usual, the scenery here is really worth looking at,

lovely hills and trees. We camped at a place called NGAPUN just above a rapid.

It was a bit dirty but considerably cleaner than YUWA and a good flat space to

move about.

Wednesday

25th

I

spent the day as usual sitting in the boat with Mummy and one or other of the

American Padres, talking and reading. We camped the night at a place called

KYAUKTINE. There was a marvellous creek, very secluded where we all proceeded

to have a good wash!

Thursday

26th

The

morning was spent as usual. There was great excitement caused in the afternoon

by an aeroplane flying overhead, everyone wished they were in it. We are now

approaching the part of the river which is full of rapids, we went over about

six today and there are lots more of them tomorrow. SONCATHA is the name of the

place where we camped, not a bad place, quite clean. We walked the last couple

of miles along a jungle track.

Friday

27th

We

made very slow progress today owing to numerous rapids; we spent most of the

day getting in and out of the boats, as everyone has to get out for the boats

to be pulled over the rapids. We spent the night at a ghastly place just above

Maw; it was very dirty and muddy. The boatmen say they might get us to HLESEIK

tomorrow if we are ready to start early. HLESEIK is where we get off the

Loondwins and we are not due there until Sunday.

Saturday

28th

We

were ready to leave this morning hours before we need as we were all woken up

by mistake at 4. 30 Am.!! We made HLESEIK and when we got there we found a

Forester to meet us, he had coolies and everything for our luggage, and took us

up to the camp, which was practically finished. The sleeping quarters consist

of bamboo huts divided into cubicles with four bunks in each. It seemed heaven

to us, after the Loondwins.

MARCH

1942

Sunday

1st

As

we arrived here a day early they were not ready for us at TAMU, so we spent the

day here at HLESEIK most people spent the time washing and cleaning up in

general. A BBTC extra assistant arrived in the morning to deal with the stores

arriving for the evacuation camps, a Mr. Middleton by name. He had his wireless

and we listened to the news and heard messages from people in Rangoon to their

families in India.

Monday

2nd

We

started out for TAMU. The luggage going all the way by bullock cart about

eleven miles. We walked for four and a half miles to a place called PANTHA with

the children in a couple of bullock carts with us, and there we got in an

almost derelict bus, and proceeded along a most frightful road to TAMU. Charles

Cook, who was in charge of the evacuation at TAMU, put us in the Court House,

the filthiest hole imaginable. Other people in charge of the evacuation are Mr.

Wright and Mr. Davies, both of the BBTC.

Tuesday

3rd

After

a considerable amount of fuss on our part, Charles Cook finally said he would

move us to the proper camp, a couple of miles outside TAMU, the camp was

practically finished with the bunks in and everything, so why we were not put

there on arrival is beyond me. It looks as if we shall be in TAMU for sometime

as coolies are unobtainable at the moment, owing to the reduced rates of pay,

and fright, a BBTC elephant gored a coolie yesterday. Fay and I found an

attractive pool in the river that runs by the camp and had a lovely swim.

Wednesday

4th

There

is no further news of coolies this morning. Mrs. Foucar washed nearly

everybody’s hair, and we spent the rest of the morning cleaning up what clothes

we could. Fay and I had another swim in the river and on our return to the

camp, were thrilled to learn that coolies had been found and that we were due

to leave in the morning. It will be marvellous to start off, as an enormous

party of non-Europeans had arrived this morning and had filled up the camp.

Thursday

5th

The

whole camp was up and ready to start at dawn, the other party coming with us,

the coolies were late in turning up! We finally got started about 11:00.a.m. We

left the other party behind as they had insufficient stores. We were only

allowed one coolie each, and they refused to carry a bedding roll and a

suitcase, so we had to repack frantically all the clothes from our suitcases

into our bedding rolls, making our beds up on our clothes , as we had to

discard our thin mattresses. The first mile was on the flat, but we began to

climb rapidly after that, it was very hot owing to our late start. We got into

camp about 2.30 p.m. it was very much unfinished, only a roof and outside

walls, we all had to sleep in long lines on the floor. Jim Davies arrived about

4.30 p.m. to inoculate all the coolies against Cholera, we have already lost

one. The water is contaminated and we have to be very careful with it.

Friday

6th

We

got up early, and had a certain amount of trouble with the coolies, after their

injections last evening. We marched seven and half miles, climbing for about

five and the remainder going down to the camp. It was very steep and we arrived

at the camp pretty exhausted. The camp itself was very nice, and was finished

to all intents and purposes; LOICHAW was the name of the place. We had our meal

and rested all the afternoon. After tea Fay and I had a bathe in the small

stream that runs below the camp. The Indian camp which is further downstream,

through which we had to pass to get to ours was burnt down owing to the Cholera

outbreak.

Saturday

7th

We

were rather late getting started this morning, the coolies were ready before

us, and we were still eating our porridge!! It was a very steep climb again

today and we were all very stiff after yesterday’s efforts. We got into camp

about 11.00 a.m. The camp consists of half a roof and nothing else! We are all

established in one long line under the half that is finished. We had our meal

and the flies swarmed around us, this is the only place we have been troubled with

them. The afternoon passed in the usual manner i.e. resting and washing. We had

just got our bedding and nets ready for the night when there was a most

terrific storm and most of us got drenched.

Sunday

8th

We

got up early but had a disturbed night, the coolies were coughing and spitting

all over the place. And some of our coolies seem to have run away which is

annoying, but we seem to be able to manage without them. I have got some nasty

blisters, which are painful. The march today was pretty stiff but we have

nearly finished with it now. We arrived at TENGNAUPAL Camp about 12:15p.m.

There are two Assam tea planters who are in charge of the camp, so things are

in a slightly better condition. There is an acute shortage of water, and we are

rationed to a pint or so each. We are over 6,000 ft. up here and it is pretty

cold. Our highest point was about 7,000 ft.

Monday

9th

We

were up early before 5 a.m. and marched for ten miles until we were about three

miles from PALEL. The march was fairly easy as it was mostly down hill and of

course we are getting into training. When we arrived at the bottom of the hill

we were taken to a small camp where there were more tea planters, they gave us

a cup of tea and put us in buses for IMPHAL (Mr Blanchard, one of the padres

had walked ahead of us into IMPHAL and got the buses.) We arrived at IMPHAL in

the early afternoon after a terrible bus ride, the road was awful. The camp is

quite nice and we were given dinner and it was good, we had proper plates,

cutlery and glasses for the first time for days and also BREAD.

Tuesday

10th

We

got up about 6:30a.m. and packed all our kit ready to put on the buses, they

were very late turning up. We had three buses between the party. The buses are

really converted lorries and had no seats and we have to sit on our luggage. We

have to go 133 miles like this but we do not mind anything now that we are

nearly at the end of our travels. Those in our bus are Mrs. Foucar, Fay, Mary,

Jenny, John, Mrs. Ricketts, Jill, and Don John, and Mummy and I. We stopped at

a place called MAO for lunch. The bus doesn’t seem to have any springs and it

certainly shakes your liver up! We passed a party of British Tommies on the

road and we waved madly at them!!

We

arrived at DIMAPORE about 7:00p.m., saw the Inspector of Police and afterwards

were given tea, with mountains of bread and jam! We had dinner in the

refreshment room on the station, the officers who were using it as a mess

waited until we had finished. Two extra coaches were put on the overnight train

and somehow or other we all got in, relieved beyond words, to have reached

civilisation again.

Wednesday

11th

We

spent the day on the ferry on the BRAHMAPUTRA River and then another overnight

train.

Thursday

12th

We

arrived in CALCUTTA.

The

Party consisted of`:

Mr.

Fletcher A.B.M. Padre.

Mr.

Blanchard A.B.M. Padre

Mrs.

Wheeler Wounded in the air raids in Rangoon.

Mrs.

Foucar.

Fay

Foucar

Mary

Mustill.

Jennifer

Mustill. Aged 7

John

Mustill Aged 3

Mrs.

Crawford

Nan

Crawford Aged 4.

Pat

Crawford Aged 18 months

Mrs.

Young An American

Layle

Young Aged 6.

Phillip

Young Aged 4

Baby

Young Aged 6 weeks

Mrs.

Johnson

Jose

Johnson

Burramia

Miss

Stewart Joined party at TAMU

Mr.

Roach Joined party at TAMU

Mrs.

Roach Joined party at TAMU

Mrs.

Ricketts Joined party at TAMU

Jill

Ricketts Joined party at TAMU

Don

John Ricketts Joined party at TAMU

Two

boys with Miss Stewart who left us at Imphal to go to school.

POST

SCRIPT

Before

we left Mawlaik we had discussions with the two American Padres who were to act

as our leaders, and they undertook to cook the rice (a large sack was loaded in

one of the boats) and boil the drinking water for the whole party once a day.

It

was up to us to provide any additional food ourselves and to allow for an

estimated fourteen day journey. We split up into small groups in our case, Mary

and the two children, Mum and I. We decided that a tin of meat or fish, plus

the rice would feed us for one meal, i.e. once opened a tin could not be kept.

So the drill was that when we camped for the night, Burramia proved him self

adept at getting a fire going and would assist the Padres in cooking the rice

and dishing it out to everyone. They also dealt with the filling of everyone’s

water bottle which had to last all day. They insisted that everyone fixed up

some sort of mosquito net at night and in the mornings we usually drank tea

with powdered milk and perhaps watery porridge, ugh! It was entirely due to the

care taken by the Padres in these matters that we all remained fit throughout

the journey.

As

to ablutions, the facilities were nil! Hence we took the opportunity to

swim/wash in a river whenever it offered! Calls of nature were just a case of

visiting the jungle and pretty uncomfortable it was! We did have toilet paper

with us I am glad to say!!? I think that at a couple of the more or less

finished camps Latrines had been dug but nowhere else! I have NEVER been

tempted to go on a camping holiday since.

When

reading this story it should be born in mind that the Burma-India border is a

very remote region and many of the place names I have given are nothing more

than locations on the map. The only places where there were any modest

habitations were either wooden or bamboo were Tamu and Palel until of course we

reached Imphal.

It

is perhaps worth noting that on the journey to the railhead at DIMAPORE we

passed through KOHIMA later to be the scene of the most important battle with

the Japanese and which stopped their intended advance into India. It was a

beautiful spot when we saw it - hard to imagine the devastation and horror that

was to come.

Although

our journey was not exactly comfortable, we were much better off than those who

came later, or found themselves up in the North of the country and hoping to

fly out from Myitkyina. There were simply not enough planes and in any event

the airfield was soon under attack by the Japanese and the refugees ended up

walking through the notorious Hukawng Valley, the rains had broken by this time

and the area was a sea of mud, very few had adequate food supplies or clothing

and many thousands died of disease.

Whilst

we were waiting in the camp at Tamu those in charge made arrangements for small

bamboo chairs on poles to carry the children and a larger one for Mrs. Wheeler

who could not walk.

The

coolies were mostly Naga tribesmen, we could not speak their language and they

could not speak ours, but we got on fine with those that remained with us. They

were keen to salvage our empty food tins possibly to make tools or weapons and

we got used to being a ‘spectacle’ when we ate our meal! Jennifer had one toy

with her - a baby doll which shut its eyes when laid down, it was an object of

great fascination to the Nagas! Jenny still has this rather battered doll!

Jose Johnson ,schoolboy in Burma , Burma to Calcutta, 1942

(source: A3338804 DIARY OF THE TREK OUT OF BURMA 1942 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Flying out of Burma

I

was born in Shillong, Assam, India on 23rd December 1932 and in 1938 together with

my parents, brother and sister we moved to the beautiful hill station of

Maymyo, fourteen miles from Mandalay in Burma. My father was an official in the

Survey of India and had been transferred to the Burmese territory

During

late 1941 the Japanese invasion of Burma was imminent and Britain and its

allies started to reinforce Burma. There was a small British army Garrison in

Maymyo at the cantonment not far from our home and the reinforcements set up

tented camps there.

There

were British and Australian Infantry Regiments stationed there and the Kings

Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) was one of the Regiments. The soldiers

favourite drinking place was Fosters’ Hotel, an establishment situated not far

from our home, which had to be passed by the soldiers on their way to the Hotel

and back to camp.

I

also witnessed columns of soldiers on route marches dressed in shorts, bush

jackets and headdress of various kinds including the Australian bush hat, with

its wide brim.

They

were always equipped with rifle, water bottle and other accruements.

Heavier

equipment was usually carried on mules or very sturdy mule carts.

Gurkha

soldiers were also stationed in Maymyo and I loved seeing them march in their

very wide legged shorts, which seemed to stand still as their stout little legs

went back and forth. This military display impressed me and probably had some

influence in the choice of my career.

In 1942 two Japanese divisions advanced into Burma,

accompanied by the Burma National Army of Aung San, capturing Rangoon, and

forcing the British forces to begin the long evacuation west. They captured

Mandalay in May 1942 and the British forces under General Alexander withdrew to

the Indian frontier.

Early that year, Joe Wamick, a Sargent of the KOYLI, was

assigned to help us with home defense. I remember helping Joe and my father to

dig a trench at the front end of our garden and to build a roof of bamboo poles

and banana leaves before covering it all with earth to make an air raid

shelter.

One day before the roof was complete Maymyo was attacked by

Japanese warplanes. We ran for the trench and I held my Daisy Airgun up to the

sky in determination to shoot them down as they flew above us. This was in

about March 1942 and I was 9 years old.

Because the Allied forces were short of equipment, many

forms of improvisation was needed to deter the Japanese enemy, and one of these

was the building of dummy Ack-Ack gun emplacements in open fields not far from

our home.

About this time my father came home one day in the uniform

of a Captain in the Corps of Indian Engineers and a few days later we prepared

to leave Burma.

The son of a Doctor Cox joined my mother and us three

children to make a party for our evacuation. Our fathers were to stay behind to

fight the Japanese.

After nearly four years of bliss in this beautiful country

this was to be the last time that we lived as a family in our own home. We had

to leave everything behind and just walk away in the clothes we wore and some

other minor articles we could carry in our hands.

All our possessions, including the many silver trophies won

by my parents in Tennis, ballroom dancing and other events were lost.

We left Maymyo by taxi in April 1942 and headed to the

village of Shwebo situated across the Irrawaddy to the north west of Mandalay.

The British army had made an airfield here and put up some huts to shelter

reinforcements, these became swamped by refugees like us very quickly.

The five of us were allocated one bed in a dormitory and

told to wait further transportation.

There was very little food and with my mother’s foresight

we survived a few days on the dried Horlicks we carried with us from Maymyo and

boiled water. There was a canteen of sorts but the food was suspect and

inadequate.

My mother discovered that there was one DC3 Aircraft doing

as many flights a day as possible between Chittagong, on the Bay of Bengal, and

Shwebo and managed to get our names on the waiting list.

I had my first lesson here of ‘relative size’; it happened when

we heard an aircraft noise and thinking it was Japanese warplanes we all rushed

outside and saw an approaching aeroplane much larger than the Japanese fighters

we had seen in Maymyo.

Word went around quickly that it was the DC3 and therefore

safe. The plane looked small in the sky but as it approached over our heads to

land, its wingspan seemed to fill the sky. Frightened, I tried in vain to run

from under its shadow.

We stayed in Shwebo for a few days and watched many people

become very sick and frightened. We were lucky and managed to get on a flight

but many were left to trek out over the mountains for the safety of India. Many

died and I met some survivor’s years later at school in India and learnt of

their harrowing experiences of death, sickness and starvation.

The DC3 aircraft had bare metal seats, which flapped up

against the fuselage wall, and a row had been added along the middle. The plane

was packed with people. As we rose into the air the seats got very cold, but

this first experience of flying was so exhilarating that nothing else concerned

me. To see the mountainous jungle below was awe-inspiring. On arrival in

Chittagong, a very hot and humid sea port we were able to catch an overnight

ferry boat running across the Bay of Bengal to somewhere east of Calcutta. This

was a fearful voyage because there was a terrific storm with thunder and

lightening and torrential rain and the behavior of drunks on board frightened

me. From our landing we were put on a train by the British/Indian authorities and

sent to Fort William at Calcutta.

We were allotted officers quarters at Fort William, which

was garrisoned by the British Army, and where we were well looked after. We

stayed here for a few days while arrangements were made for our onward

destination. My mother was able to contact her sister in Lahore, over in the

Northwest of India and arrange for us to live at her home. With this the Army

allowed us to leave the Fort and we set off on the long rail journey to Lahore.

I never knew what happened to Derrick Cox, the doctors’ son who came out of

Burma with us.

Clearly, my mother must have had a very trying time and

showed her determination and strength.

My father spent the next three years as part of the British

14th Army opposing the Japanese Army in Burma.

Richard Hurley, schoolboy in Burma, Calcutta, 1942

(source: A4036961 A British Boy in Wartime Burma at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Escape down the Irrawaddy

My

parents were in Burma at the start of the war, having sent me back to England

in 1937 at the age of 5. I stayed in Yorkshire with my grandmother.

My

father had passed the Indian Civil Service exams and by the outbreak of the war

he was the Commissioner of the Irriwaddy Division. The Japanese invaded in

1941/2 and civilians started to move north away from the invading army. Many died

on the walk.

My

father requisitioned boats in the Irriwaddy Flotilla and sent my mother south

(towards the Japanese!) down the delta to the coast and round to up to Akyab

and from there up to Calcutta.

My

father followed the same route later as the last to leave. Together my parents

travelled from Calcutta up to Simla and then across to Durban, Cape Town and

back to England in the spring of 1943. I had not seen my parents for 6 years.

John Bennison, Agnes Bennison, Commissioner of the Irriwaddy

Division, Calcutta, 1942-3

(source: A3453716 Lateral Thinking at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

To Calcutta through the storm

We

didn’t have to report in at Mhow for another 2 weeks anyway. However, within a

couple of hours or so upon arrival in Rangoon we were once again airborne in a

Dakota, bound for Calcutta. These planes had not been used for dropping supplies,

therefore no seats! Halfway up the coast of Burma we ran into a storm,

lightning flashing all around, buffeting around, dropping like a stone and then

flying at tree top height. Indian soldiers on the plane were on there knees,

praying as hard as they could. After landing at Calcutta, we were informed

that a Dakota which had taken off just before us, had crashed in the jungle!

So,

that very same day, from being south of Kalaw at 8.00, found us at Calcutta airport not really knowing what to do next, certainly not

getting to Mhow before we were supposed! We stayed a few nights at the

Salvation Army hostel and spent the days looking around Calcutta. Soon tiring of the masses, the beggars, the sick and the

dying and the young, I decided we would take a circular tour of northern India

by train.

Ronald Hodgson, Army, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A5961170 The Black Cats: Part 3 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Escape from Burma

I

spent most of my childhood in the Far East — Burma.

My

father was in the Colonial Service. I had an unusual and privileged upbringing

until the war started, and was at school at a boarding school in Rangoon. I was

12 years old. Father had an elephant that he used for his touring as part of

his work and as a treat, when it came for medical attention each year from the

Arakan - Yomas mountain range, we rode it round the town!

The

Japanese had started their invasion of Burma, Singapore had fallen and they

were moving across to Mandalay where we were stationed at the time.

We

were asked by the Government if we wanted to evacuate, so a group of about 20

started our trek from Mumbai to the Indian Border. We walked for about 14 miles

a day, from camp to camp. We had a soldier at the front and the back for our

protection. Coolies carried our treasures and essentials and everyone was

allowed to take 60lbs in weight of possessions, but as children we took our

treasures, rather than essentials. We took quite a lot of money which my

brother carried in a money belt. The camps, of bamboo huts, were constructed

for us. I was with my mother who was 40, and my two brothers, one older, one

younger, and we were the only children on the walk. When we left we were told

to bring provisions (mainly tinned foods) that had to be ‘handed in’ and then

from then on we would be feed. We were up at 4 am, and walked until about 11

am, from one camp to the next, where we were given rice or lentils to eat,

nothing much more and then rested for the rest of the day. As children, we

thought it all a big adventure. Mother had asthma and had to rest and at times

she had to be carried in a sedan chair. Everybody helped each other and we

bathed in the rivers to keep clean.

And

the next day came more walking, and for the next 21 days until we came right to

the border of India. From there we took a bus into the Head of the Railway. We

got the train to Calcutta where we were billeted in a convent, sleeping on the

ground. We were grateful for a mattress and to be under cover as we had been on

the move for 2 months. As children we were delighted to see ice cream on a

stick!

The

authorities asked us if we had any relations, or places that we wished to go.

We had an Aunt in New Delhi, so we went there and the remainder of the group

went to another camp down south. From there we went to another Uncle at

Lucknow, who had 5 children. We were asked if we wanted to go back to school so

my brothers went to a Christian Brother’s school and I went to a convent. We

were all day pupils.

My

Father eventually came across from Burma. He walked with part of the 14th Army

to join us, up until then we had been very much alone with my mother and in the

end, we went back to Calcutta, once more a family.

Thelma Jolly, Rangoon Schoolgirl , Calcutta, 1942

(source: A5230450 A Childhood in Burma at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

I was a young Indian (Parsi)

girl living in Calcutta

I was a young Indian (Parsi) girl living in Calcutta during World War II. My family consisted of my mother, father and three daughters, I was the eldest daughter. My brother had not been born yet. We lived in an apartment block in Mission Row, not far from Dalhousie Square — the spot where the “Black Hole of Calcutta” was supposed to have taken place — though Indian historians deny this episode.

My neighbours consisted of a Chinese family who had trekked from Burma, an Anglo-Indian family - Mr and Mrs Carter, a Portuguese family — Mr and Mrs Coelho and their 4 sons, and 2 Baghdad Jewish families — the Nahoums and the Manassehs.

My family lived on the top floor and from our veranda (whose doors and windows had been plastered with black and brown paper, as protection from broken glass during the air raid), I could see the steeple and weather cock of St Andrews Church, and in the background Howrah Bridge, the life-line of Calcutta connecting the 2 sides of the mighty Hooghly River.

Katyun Randhawa, a young Indian (Parsi) girl, Calcutta, 1942-3

(source: A5756150 The bombing of Calcutta by the Japanese Edited at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

Escape from Burma

My

dad came to Burma in 1923 from America with fellow countrymen to work for The

Burma Oil Company, to help to open the oil fields in Yenanyung alongside a

British workforce. Travel in those days was on horseback.

My

mother was Burmese and I was born in Yenanyung. When we were of school age we

had to go to Rangoon for our education. My brother, Clyde, was first to go.

Five years later I went followed by my sister Ethel. We had to stay with my

mother's relatives. My brother and sister stayed with my mum's sister,Lucy, who

already had five children of her own. They lived in Rangoon.

I stayed with my mother's aunty and family. I don't know why but I called them

Nana and Grandpa. I suppose it was because they had a grandson.I was educated

at St.John's Convent in Rangoon. I used to travel by train. It was a pleasant

journey. My school days were happy days but I did not enjoy holidays, living

out of town, not seeing my school mates, but I enjoyed both cultures.

There

was always some kind of celebration among our Burmese neighbours and we all

joined in. There were street parties, water festivals and as we were

Christians, Easter and Christmas were very special. We went to church most

Sundays and after the service we used to go and have a meal in the market

square. Very enjoyable.

Grandad

worked at the High Court, he was the Clerk. He went off to work in the morning

and in the evening, after work, he would go shopping and bring food in for the

evening meal. I used to love nana's cooking and loved watching her prepare the

evening meal.We were all more then ready to eat.

I

did not see a lot of my brother,sister or mother but I do remember the three of

us going to visit our mother. We had to take the river boat on the Irrawaddy

River to get to Yenanyung and it was very exciting for the three of us to be

together to visit our mum, even though it was only for a short time. As mum and

dad were separared we did not see dad.

One

time we returned nana and family were not very happy, I did not understand why.

They were discussing war and were very worried. It wasn't very long before I

realised why they were so worried.On Christmas Day 1942 Rangoon was bombed and

we all had to find shelter. Nana told us to soak whatever we could find and to

cover our mouths in case it was a chemical attack.Fortunately it was not.When

the bombing stopped, we ran out to see the damage but all we could see were

palls of smoke on all sides. We felt trapped with nowhere to run, no escape,

only to be burnt alive.Everyone was in a panic- a very frightening experience.

Nana

and family realised it was the beginning of of the Japanese invasion and by

evening, where we lived was like a ghost town. Where everyone had disappeared

to we did not know.

Out

of 90 houses in our street there were only 4 houses left occupied, it was very

scary. Everything was so quiet, eerie, where everyone went to this day we did

not find out. After a couple of days things did not look too good so nana and

family decided we had better move on like the rest as the place was like a

ghost town. Like everyone, we just took only the very necessary things we could

carry and left everything behind us. We went to stay with friends 20 miles away

but did not realise what hardship was to follow and that this was just the

beginning. It was just as well we left because a few days later our house and

the area we lived in was bombed and everything raised to the ground. We were

lucky to have left in time.

Things

did not look too good. We could not get in touch with any of our family. It was

utter confusion with no one to guide us or tell us what to do or where to go.

It seemed every family had to make their own decision. My sister, Ethel, had

just started boarding school and we were unable to contact them.

the

Japanese army was fast approaching. The elders decided we had better go north

and put as much distance between us and them as possible, so off to Mandalay we