Demonstrations and Agitations

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

● Sitemap ●

Reference ●

Last

updated: 19-May-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If there

are any technical problems, factual inaccuracies or things you have to add,

then please contact the group

under info@calcutta1940s.org

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

Calcutta as one of the birthplaces

of modern Indian nationalism, and as host to one of the most educated and

advanced of Indian populations had always been a hotbed for political activity

and agitation.

Throughout the 1930s, the genteel

well chaired debates in public halls became increasingly a thing of the past

and political agitation took to the streets to address the increasingly

politically aware masses.

Even in the tense and politically

repressive situation of the war did not stop the Calcuttans from coming out and

making their voice heard.

The quit India movement broke

through it and from then on till independence and beyond the political,

communal and economic situation always provided enough issues to spark of

protest in a great variety of forms.

Small meetings, speeches, mass

ralleys, political leaflets and magazines, strikes, protest-marches, sit-ins,

riots, mutinies, terrorist attacks and hungerstrikes; all were used to make

one's opinions and grievances heard and felt.

They seemed to be so frequent that

almost independently of the actual cause they became a prominent (and in some

case permanent till today) feature of life in 1940s Calcutta.

[Please note that some of the

greater agitations, namely the communal tensions of 1946, and the Communist

agitation are dealt with in separate chapters. ]

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

Tram workers on strike

Indicative of the resumption of an age-old struggle for decent conditions is this immediate post-war picture of tram-workers on strike. The strike lasted nine days but employees won par of their demands.

Clyde Waddell, US military man, personal press photographer

of Lord Louis Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix magazine. Calcutta,

mid 1940s

(source: webpage

http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson,

South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania)

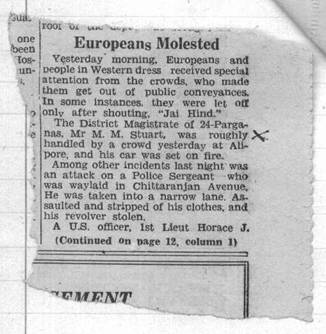

… and his car was set on fire

Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart, I.C.S. (Indian Civil Service) District

Magistrate 24 Parganas, Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005 /

Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

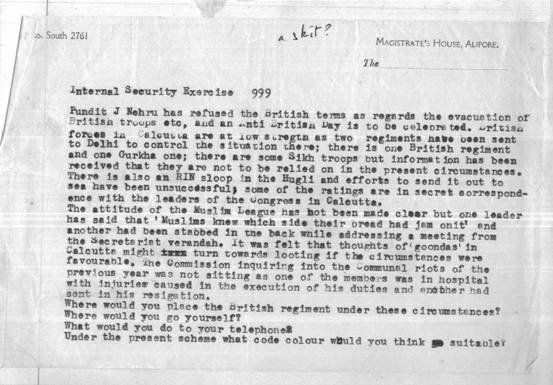

Internal security exercise 999

Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart, I.C.S. (Indian Civil Service) District

Magistrate 24 Parganas, Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm

Moncrieff Stuart O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on 20-Dec-2005 /

Reproduced by courtesy of Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

The Spinsters

AFTER years of yarn-spinning Congress Committees have become experts in framing the resolutions which, as Mr. Gandhi puts it, "reflect exactly all shades of opinion in the Congress" and therefore put everybody in a flat spin. From this point of view the Bardoii resolution is entitled to the Mahatma's description of it as "flawless". No sooner was it issued than the teleprinters were flooded with statements from leaders of "all shade's" each giving it a different interpretation to suit himself. '' Violence, says Dr Rajendra Prasad, has never settled anything permanently.” Of course not; because nothing is ever settled permanently. The doctor wants a static world, but he will never find it. The world has evolved through a long course of wars on an ever larger scale. Now we have reached total war which is bound to lead to a long period of total world peace. In that millennial period (Hitler on the assumption that his side will win-puts it at a thousand years) the human race will doubtless be devising new struggles, preparing for the conquest of Mars or the moon. "The war of the worlds", interplanetary war, is what most speculators who foresee peace on earth and realize that time with no beginning and has no ending, finish by predicting, e.g. Mr. Wells in "The Shape of Things to Come".

But even that interplanetary war- may, according to the traditions preserved in scriptures of all religions, be a variant in a recurring cycle, the "war in heaven" that Milton chronicled.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, January 18. 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

War Attitudes

MAULANA Abul Kalam Azad and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru are reported to have promptly told a questioner that “It is foolish and useless to resort to satyagraha when the enemy threatens,". That, we hope, is the end of that. It is still some what puzzling that, when the enemy threatens, Congress seeks counsel from Wardha.' it would be helpful if at this Juncture Mr Gandhi were to say that the advice he gave "to every Briton" in the critical hours of 1940 to invite Hitler and Mussolini in and offer them whatever they wanted is not the advice he would not give to us in India.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, March 18, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Letters:

In Sorrow

Sirs:

This note is written more in sorrow than in anger, regarding your article

on India [TIME, March 16]. . . .

Your article cites that in 1857, during the Great Mutiny, the Moslems

were sewn into pigskins before being shot, but it does NOT mention the Black

Hole of Calcutta, or what necessitated, in the opinion of those responsible,

drastic reprisals. Nor does it point out that it was the religious fear of

pigskin, rather than death, which broke further mutiny.

Again, you cite the case of General Dyer's dispersing a prohibited

meeting by firing into the crowd; but you do NOT mention that General Dyer was

relieved of his appointment in consequence, and died a broken man—in spite of

the fact that many of those best able to judge feel that, if he had not taken

his drastic action, once again India would have been torn end to end in mutiny

and civil war. . . .

Could and should not it have been pointed out that:

There are less than 600 Englishmen in the entire Indian civil service.

The Indian Government has been highly protected AGAINST Great Britain,

and that only about one-third of India's trade—import and export—is with that

country.

Britain's "loot" from India is about 5% on an investment of

some 4 billion dollars.

Great Britain itself has trained the leading Indian politicians in British

universities to absorb British ideas of Freedom and Democracy.

The real parasites of India are—

1) The 14 million head of Sacred Cows

2) Child Marriage

3) Lack of Sanitation and

4) Certain Indian Princes and so-called "Holy Men."

To make sudden and drastic changes to India's administration of

352,000,000 semi-civilized people, with over 45 races with 225 languages, many

religions, and diametrically opposed ideas, was—and to many people's minds

still is—an impossibility; and that if there ever were cause for "the

inevitability of gradualness," here is one indeed. . . .

M. P. TUTEUR

Captain, Lahore Division

Indian Expeditionary Force, 1914

Toronto, Canada

>TIME said there was a British case, and Reader Tuteur states it very

effectively.—ED.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Apr. 6, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

Revolutionary

violence was endemic

It was an exciting and stimulating time for a young man who was ready to burn the candle at both ends. Revolutionary violence was endemic in a small but fanatical minority of a people whose language and culture was different from that of the rest of India; who had an ancient grievance against authority since the days of the Moguls; and who carried the stigma of an unmartial race. It fed on the resurgence of Asian nationalism after the Japanese victories over the Russians at the beginning of the century, was fanned by the discontents flowing from the first partition of Bengal, and later from the liberal and methodical steps towards self-government to which the British rulers were already committed, and which therefore gave the movement the colour of a war of independence.

John

Christie, civil servant, Calcutta, late 1930s

(source: page 52 of Trevor Royle: “The Last

Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

Trouble

on Sealdah Bridge

She [my mother] had been brought up in Ishapore where her childhood had been dominated by a sense of ease and privilege. The club had been the focus of the town's social life where she had learned to play golf and tennis, to ride and dance and to get to know everyone in the tightly knit British community. It was the kind of life which she thought would never come to an end: Her [my mother’s] first inkling that things might be starting to fall apart had come in the late 1930s, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

A boyfriend [of my mother’s] had been bitten by a native dog while breaking up a dog fight and had been taken into hospital in Calcutta for a painful course of rabies injections. The treatment lasted three weeks, so to keep him company she and a party of chums would take him into Calcutta and then go to Firpo's for coffee and ice cream.

It was a short enough trip [from Ishapore] into Calcutta, one that was usually as free from incident as any commuter journey; but one day they ran into trouble. Big trouble.

Approaching the Sealdah Bridge, they were stopped by a crowd of angry Indians, all wearing Congress caps and shouting political slogans.

'Don't drive those people,' they told the driver. 'Get out and let them walk! Don't drive them!'

In the best traditions of British pluck, the young man who had been given the course of injections was equal to the task. Fearing a calamity unless he acted quickly, he drew out his pipe and stuck it in the driver's back. 'This is a gun,' he whispered. 'If you don't drive on, I'll blow your head off!' The terrified driver changed down a gear, slipped the clutch and charged the car over the bridge, spinning several of the demonstrators on to the walkway.

For the party it had been an unnerving experience and their first real taste of the strength of Indian nationalist feeling. Yet, as they drove back to Ishapore, they became aware of the paradox that, however raucously the Indians might have been protesting and however frightening the incident might have been, British rule still stood firm in the face of that discontent, that measured tones and a pipe masquerading as a pistol could still uphold the mystique of the British Raj.

Trevor

Royle, writer, Calcutta, late 1930s

(source:

page 16 of Trevor Royle: “The Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph,

1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

08

August 1942 - Quit India Resolution

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Toward

Disaster?

India's week began and ended with deceptive quiet. In the cooling

monsoons of central India the Congress party Working Committee met with

Mohandas Gandhi at Sevagram. Monday was Gandhi's day of silence, but Tuesday

morning the silence was broken. Correspondents were summoned to receive the

committee's decision. In a high-pitched, whistling voice, the 90-lb. archenemy

of the British Raj declared that, from now on, the people of India would be in

open, nonviolent rebellion against British rule.

By Wednesday morning the resolution had reached New Delhi. The Viceroy's

Council met in the long, high-windowed council room, darkened against the

glaring sun. What they would do was a foregone conclusion. The British

Government of India does not possess the authority to commit Constitutional

suicide; at best it could refer the decision to His Majesty's Government at

London. This it did.

In New Delhi nothing except muted headlines indicated that India was

approaching a rendezvous with history. Heat-drugged, half-nude Indians still

slept in the shade on sun-baked pavements or sprawled dozing on the grassy

lawns of Government buildings and homes of pukka sahibs. From miles away bright

British flags could be seen snapping in the north wind above the copper dome of

the viceregal palace, as gayly and unconcernedly as if the British Government

were not facing the most serious threat to its power since the Mutiny of 1857.

The Threat. The core of the Congress resolution demanded that Britain

withdraw politically from India, and threatened to use all the possible

nonviolence of the people to compel Britain to withdraw. The resolution did not

alter Gandhi's position that he does not wish to interfere with United Nations

military forces in India (TIME, July 13). But Jawaharlal Nehru explained that

nonviolence envisaged more than industrial strikes—it would be a general

strike, peaceful rebellion. Nehru's thesis was simple: only Indians could

organize India for war, because anybody could do anything better than the

Government of India today—that is a fundamental axiom."

"I think this may be illegal," said one British official after

he finished reading the resolution. There was no doubt that, by the law of India,

Nehru, Gandhi and every member of Congress was subject to arrest. Gandhi and

Nehru, both astute lawyers, knew the law. But both they and the British knew

that India's problem was not to be solved by legalities.

How far did Congress represent India? Never had Congress entered mass

action with so much of its own press against it. The Bombay Chronicle, Lahore

Tribune and Madras Hindu assailed the Congress policy. The great Madras leader

Chakravarti Rajagopalachariar ("C.R."), who recently resigned from

the Congress, was speaking against its policy publicly, though hissed and

booed. Dawn, the organ of the Moslem League, which represents some, but far

from all, of India's huge Moslem minority, was crying that Britain's yielding

to Congress would result in "the rule of the jungle, anarchy and

disorder."

But Congress, the most powerful political group in India, has roots in

the illiterate, hungering Hindu peasantry, in Hindu shopkeepers and middlemen,

thousands of English-speaking Hindu intellectuals. The silver-haired Nehru,

honestly and brilliantly antiFascist, believed that India would repeat the

history of Burma and Malaya unless Indians could be persuaded to take part in

its defense, and that they would take part only if they felt themselves free,

not slaves. Gandhi, with a great emotional understanding of the small peasants,

apparently sensed that at last had come the moment of British embarrassment in

which to launch his fifth nonviolence campaign.

Hour of Decision. The Government of India and Congress had matched

strength four times previously, but this time the result might be different.

Congress insisted that it would not yield an inch. So in private, did the

British. Like the antagonists in a great tragedy, the two forces seemed to be

moving along appointed grooves to an appointed, unalterable end—disaster.

But not until Aug. 7 would the Congress Working Committee's proposal be

submitted to the party's general committee. In the meantime many things might

happen, many other counsels might prevail. At week's end one of the Congress

papers attempted to suggest an alternative. Said the Delhi Evening National

Call: "As we look around we find that there is only one man and one

country that can save the United Nations from a fatal catastrophe and the cause

they represent—that man is President Roosevelt and that country is the United

States."

It was a week of history in India, but it seemed that less than 1% of 1%

of India's millions realized its implications. Along the fringes of India

blackouts reigned in Calcutta, Bombay and Colombo, but nightclubs plied their

trade and hotels were fuller than ever. Chief event of the week was the

departure of Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester. A conscientious soldier, the

Duke had made an exhausting 9,000-mile trip from one end of India to the other,

holding countless reviews, eating innumerable dinners with princelings,

ministers and soldiers. He was called "Sunshine" by newspapermen.

Despite the heat, the Government hung on doggedly at New Delhi as a

gesture to the war effort. Air-cooled movies offered U.S. pictures. But none

could compare with Jhoola, an Indian epic of love & song running riot in

its 21st week to enthusiastic audiences at the Jubilee Theater.

It seemed impossible for both Americans and Britons, fresh out from home

and arriving full of vim & vigor, not to fall into the cushioned grooves of

normal Delhi society. Americans were happy with a new batch of air mail,

including copies of TIME. But they itched and scratched with prickly heat; some

of Delhi's victims treated it with table salt, others used antiseptic

solutions; all scratched.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Jul. 27, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Quit India

MR Gandhi is a source of much difficulty. Unquestionably he has made a number of contradictory and irreconcilable utterances. In this week's Harijan he seeks to reassure the British public by paraphrasing the Resolution thus: "India is not playing any effective part in the war. Some of us feel ashamed that is so and, what is more we feel that if we were free from the foreign yoke, we should play a worthy, nay a decisive part, in the world war which has yet to reach its climax". Now this is language that might have been used by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru or Mr Rajagopalacharia , but it is in flat contradiction of Mr Gandhi's "Letter to Every Briton" advising abject surrender to the enemy. That letter he recently reaffirmed, and he said that in the present situation he offered Indians the same advice in relation to the Japanese. He has also recently talked of a free India seeking to negotiate peace in Berlin, Rome and Tokyo.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 5, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

So What?

THE finger of fate moves on, and new lines in the Indo-British chapter arc being rapidly written. The Congress has adhered to its resolution, after proving to its own satisfactionthat Britain is in the wrong. The Government of India has replied by arresting the leaders and issuing stern orders for the suppression of the threatened civil disobedience if it starts.

This is a military question. The Allies can and must now think only in military terms. Common salvation is essential. The BBC announcing on Saturday night the passing of the Congress Resolution called it the "Quit India" resolution, thereby refusing to distinguish between it and the Allahabad resolutions of more than three months ago, or to accept the explanations, of the July resolutions given in much detail at Bombay. The Government of India's Resolution issued on Saturday immediately after the AICC had endorsed the July resolution also rejects the face value of this resolution with its offer of cooperation in the war. It pins the Congress to its Allahabad resolution, and it interprets the whole as an invitation to anarchy. The future alone will reveal whether the BBC and the Government of India are speaking for the Allied War Council.'

If they are, if this is the considered view of the supreme military direction, it will, of course, stand. In that case the announcemcnts in the form they have taken are for the information, both of the Allied countries and of the enemy countries and we must assume that it is considered good propaganda to emphasize, elaborate, and insist in front of an enemy which has forced us to quit Malaya and Burma that the Congress has asked us in the literal sense to quit India. On the other hand if what must prove one of the most critical military decisions of the Allies has been taken without reference to the War Council by the Home Department of the Government of India and the bureaucracy of the India Office, and if the Government Resolution and the BBC announcement are arguments addressed to the Allies and the Supreme War Council for the retention of their powers they may be subject to revision in the light of the stern necessities of war.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 10, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Frogs

in a Well

A small boy in a tattered dhoti idly dawdled toe marks in the deep dust.

Monsoon skies were slate-grey overhead. The oppressive heat gave added pungency

to the smell of human filth in the Girgaun district of Bombay's slums.

Shopkeepers moved listlessly; talk dribbled in the bazaars. Suddenly everything

changed. Word sputtered from mouth to mouth that the British Raj had jailed

Mahatma Gandhi.

No longer listless, Hindus in the Girgaun ran riot. Four double-decker

busses were wrecked. One was set afire, blazed high in the sky. Traffic

snarled. Foreigners were stoned. So were police, who answered with tear gas,

then fired directly into the crowds. The small boy ran from one trouble spot to

another. Finally he remembered some blackjacks that he knew about. He got them,

took up a stand on the street corner, sold them for one rupee each.

Thus last week did a tragic hour, damned by logic and twisted by

emotionalism, come to the subcontinent of India. In a crisis caused by Mohandas

Karamchand Gandhi's threat of open revolt, the British struck first. The

slamming of jail doors on the leaders of the Indian National Congress party was

their answer to Gandhi's demand for immediate Indian independence.

The Hour. In the dawn's early light, Bombay's police commissioner

arrested Gandhi at the home of Ghanshyam Dass Birla, a wealthy Indian

industrialist. The elderly Pied Piper, who had been up until 2 a.m. writing

reports and memoranda, was sleepy but good-humored. He was given an hour to get

ready. During that time he had a breakfast of orange juice and goat's milk. He

heard a Sanskrit hymn and a few words from the Koran, read by a young Moslem

girl. He scrawled a last-minute message to his followers. Then, with a copy of

the Bhagavad-Gita (sacred Hindu poem), the Koran and an Urdu primer under his

arm, a garland of flowers around his wizened neck, he was taken in the

commissioner's car to Victoria station. "Nice old fellow, that

Gandhi," the commissioner said. The train chuffed on to Poona. There the

Mahatma was imprisoned in the rambling stone "bungalow" of the rich

Aga Khan.*

With Gandhi went Mme. Sarojini Naidu, poetess, and Madeline Slade, the

British admiral's daughter who has been Gandhi's devoted follower for 17 years.

Mme. Gandhi, older (73), tinier (barely four feet tall) and far frailer than

her scrawny spouse who is still tough as nails despite the fiction that he is

sickly, was allowed to remain in the Birla home. But that evening, she, too,

was arrested when she tried to make a speech before 30,000 persons in a big

Bombay park. The meeting was broken up, but not before other speakers read the

last message from Gandhi: "Every man is free to go to the fullest length

under ahimsa (non violence) for complete deadlock by strikes and all other

possible means. Karenge ya Marenge! (Do or Die!)

The Presidents. Nearly 200 party leaders were rounded up and jailed.

White-capped Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi's leading disciple and right-hand

man, who is also a well-proven friend of the United Nations, was sent to

Yeravda, six miles from Poona. Into the same jail went white-bearded Maulana

Abul Kalam Azad, President of the Congress party. A few minutes before his arrest

Azad smuggled out a message: if party leaders were seized, "every Congress

member becomes Congress President."

This message, coming before Gandhi's set off the first riots. It was read

by a woman in the canvas tentlike Pandal, where 250 party leaders of the day

before had voted (with 13 opposing) authorization for Gandhi to lead his last

great civil disobedience campaign. Scattered by police who threw tear-gas bombs

and whacked heads with lathis (five-foot bamboo staves), Gandhi's followers

quickly reassembled in the streets. Hundreds threw stones and vegetables at

police who rushed the Bombay provincial party headquarters and seized all

administrative documents. Before nightfall, when reserves of British officers

and yellow-turbaned native police were held in readiness for blackout riots, at

least eight persons were killed in Bombay alone. In 48 hours police and troops

fired "about ten times" into unruly mobs. The list of bullet-wounded

soon passed the hundred mark. Bands of men and women lay down on streetcar

tracks or piled rubble on the rails. Others hauled passengers out of

automobiles and forced cyclists to dismount with the admonition that they must

walk "because this is a democracy." Growing nastier mobs began

stoning foreigners. A.P. Correspondent Preston Grover's car was shot at,

bombarded with bottles, rocks, chamber pots.

Spreading from Bombay, the riots took on increasingly serious

proportions. At Poona 14 were injured when goondas (Hindu for hoodlums) threw

bottles into windows. At Lucknow, police fired on student demonstrators.

Demonstrators stoned trains, cut wires, smashed police lamps. In Ahmadabad

police killed one person when they fired directly into a mob trying to burn the

police post. In New Delhi a small crowd fought its way past a barricade at the

foot of the hill leading to the Viceroy's palace, but later was turned back.

Whites in New Delhi said: "It's here," kept close together for mutual

protection. In Calcutta there were

demonstrations, but no immediate strike call for war workers in strategic

factories. The British feared that communal riots between Hindus and Moslems

might break out. The stoning of Moslem shops by Hindus in Bombay was one

portent of even greater trouble.

The strategy of the British Raj was plainly to strangle what it called

"open rebellion" before the rebellion could get organized. The

British hoped to quell the riots in a few days, expected support from

Communists, Untouchables, Moslems. Their program was ready for the push of a

button. During the week the Viceroy's Council met almost daily instead of once

a week. It was a period of great decision for the eleven Indians on the 15-man

council. If they approved the arrest of Gandhi, it meant that their decision

would haunt Indian politics for decades. It would cut them off from any

Congress party support. On the fateful Friday they trudged three times up the

winding spiral stairs of the Viceregal lodge to the Council Room. They left

late at night with their decision made, their plans laid.

In moves that meant total war against the Congress party, with the

backing of the Viceroy, the 2nd Marquess of Linlithgow, and the Home

Government, the Council: 1) ordered strict control of the national press; 2)

gave provincial authorities power over local governments; 3) announced that

shops closing their doors as a part of a general strike would be immediately

taken over by the Government. When the hour came the British operated with

extraordinary efficiency.

August 7. Just as they struck first at week's end, the British struck

hard earlier in the week with the revelation of documents seized last April in

a raid on the Congress party headquarters at Allahabad. These documents were

used to prove that Gandhi at that time had planned, as the first act of Indian

independence, to negotiate for peace with Japan. Nehru and Gandhi promptly

noted that the raid was illegal, claimed that the documents were misinterpreted

by the British to influence

U.S. opinion and turn Gandhi supporters against him in Britain. To the

British, the documents were evidence that Gandhi was a traitor. To the Congress

party the British action was a dirty trick. Meeting in Bombay, on the fateful

August 7, the party gave its answer.

Of all India's cities, Bombay represents the best and the worst that the

Raj has brought—from enlightening contact with western civilization to the

tragic abuse of industrialism expressed in miles of grimy slums like those in

the Girgaun district. In this poverty-riddled, proud, resplendent citadel on

the seven interwoven islands at India's gateway, the Congress leaders met with

settled purpose. Inside their huge Pandal electric fans hummed. They had the

unprecedented extravagance to provide chairs for everyone. They opened their

meeting with terrific trumpet blasts. A band played Marching Through Georgia.

Crowds surged on Gandhi when he arrived in his loincloth, a narrow white scarf

around his neck. Twice he lost his glasses. Each time his admirers tried to put

them back on for him. Momentarily forgetting nonviolence, he swung his fists to

ward off the overzealous. Inside the Pandal, Gandhi spoke, cross-legged from a

couch, into a microphone. A friend explained: "He has some difficulty

because he has lost his teeth."

Friends. But Gandhi had not lost his wits. He handed U.S. correspondents

a "letter to American friends" urging that the U.S. intercede for

Indian independence. "You have made common cause with Great Britain,"

he said. "You cannot therefore disown responsibility for anything that her

representatives do in India." He contended that "false propaganda had

poisoned American ears," ended his letter with the salutation: "I am

your friend."

At the Pandal microphone Gandhi also professed his friendship for the

British: "I know that they are on the brink of the ditch, and are about to

fall into it. Therefore, even if they want to cut off my hands, my friendship

demands that I should try to pull them out of the ditch." Sadly, as if the

British were tired little children, Gandhi explained that the British position

in India could be saved only by granting the Indians freedom. "We can show

our real grit and valor," said he, "only when it becomes our right to

fight. My democracy means that everyone is his own master. . . . We do not want

to remain frogs in a well. We are aiming at world federation. It can come only

through nonviolence. Disarmament is possible only if you use the matchless

weapon of nonviolence."

Nehru. From such lofty thoughts in the midst of a ruthless world war,

Gandhi turned to Pandit Nehru, gave him credit as "my guru" (teacher)

in international affairs. Said Gandhi: "I do not want to be the instrument

of Russia's defeat, nor China's. If that happens, I would hate myself."

The voice was Gandhi's, but the sentiments were those of Nehru, torn between

his knowledge of the world and his love for the Mahatma. Grave and drawn was

Nehru's face when he rose to speak. There was finality in his words. He spoke

of a British "defeatist attitude," urged that "valiant fighters"

replace the "creaking, squeaking and shaking machinery of the Government

of India." He urged that Hindus "give up that attitude of mind which

welcomes the Japanese." He drew the session's loudest cheers when he

suggested participation of a free India in the ranks of the United

Nations.

When the session closed, Gandhi had authorization to call for a

satyagraha (civil disobedience campaign) which had been recommended by the

Congress working committee on Aug. 7. It was a powerful weapon in his hands, a

weapon the British called blackmail. To Gandhi, a crusader with a one-track

mind, it was a weapon with which to bludgeon immediate independence from the

British. He said he hoped President Roosevelt would intercede and announced he

would make a last-minute appeal to the Viceroy before leading his followers

into action. But there was no time: the next morning the Indian Government

cracked down.

Claims. In the British House of Commons, Indian Secretary Leopold

Stennett Amery admitted that "Gandhi has his own idiosyncrasies." But

Amery thundered that Gandhi's action in calling for civil disobedience was

"a stab in the back to all who are fighting in India, or for India, in the

cause of the United Nations, whether they be Indian, American or Chinese."

The British position is that, in wartime, Gandhi's mysticism, his

saintliness, his idiosyncrasies and his shrewd playing of politics do not

excuse treasonable acts. As

blunt as a lathi is the Government's claim that Gandhi is both an

appeaser and pro-Japanese traitor.

In Nehru the British have seen a fine mind, an incorruptible honor, an

intelligent approach to world problems. But they distrust him because of his

faith in Gandhi and an emotionalism which led him to say: "We prefer to

throw ourselves into the fire and come out a new nation or be reduced to

ashes." To finish off their case against Gandhi and Nehru, the British

official position is that Gandhi's voice is not the voice of India. They claim

that his party is losing power, that it cannot possibly represent all of

India's heterogeneous peoples and makes no attempt to do so. If immediate

independence were granted to India, it would mean a one-party political

dictatorship, immediate civil war and chaos that would provide easy entry for

Japanese invaders.

Counter-Claims. The Indian view, as brought back to the U.S. last week by

Correspondent Louis Fischer after a week's conversations with Gandhi, is that

the British are "smearing" Gandhi and wooing U.S. public support of

an oppressive, undemocratic and inefficient Indian and colonial policy. Sir

Stafford Cripps, said Fischer, at first led Indian leaders to believe that they

would receive a free rein in running their affairs. Subsequently, said Fischer,

Sir Stafford was tripped up by Empire politicians. Amidst a wealth of verbiage

and argument, Fischer found a sound point in claims that free Indians would

fight invading Japanese; and that, inversely, if India's long-smoldering hatred

of the British is fanned, the Indians may be apathetic to "new masters."

Although Gandhi once may have been flirting with the Japanese, either out

of unworldly wisdom or as a counterfoil to the British, the final draft of the

"Quit India" resolution was pro-Ally. Also on the record is Gandhi's

petulant manifesto last fortnight to the Japanese: "Our offer to let the

Allies retain troops in India is to prevent you from being misled into feeling

that you have but to step into this country. If you cherish any such idea, we

will not fail to resist you with all the might we can muster."

The Spectators. Said a leader in the New Delhi Evening National Call:

"Britain has opened up a second front. The blitz is on. . . . She has

drawn first blood. There is thunder in the clouds and lightning flashes

surcharge the horizon." But the green, white and gold banners of the

Congress party hung limp and forlorn from Hindu shops in Delhi. Just as forlorn

were U.S. officials in India. Quietly, quiet Lauchlin Currie, special U.S.

envoy to the Chinese government, slipped into town. After him came Lieut.

General Joseph W. Stilwell, Chiang Kai-shek's Chief of Staff and Commander of

U.S. Forces in China, Burma and India. Representatives of a nation which 167

years ago rebelled against British imperial rule, they were witnesses to

another struggle for freedom. Plain to see was the tragedy of India. Not so

plain was the part that the U.S., with all the good will in the world, could

play.

It was only a year ago that Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill

asked the world's admiration for their Atlantic Charter. It was a pledge of

sorts, even if Churchill subsequently announced that it did not apply to India

(and Burma) and the British colonies. And Americans, despite a generally

pro-British and occasionally miserably misinformed interpretation of the Indian

question in press and radio, were aware that in India the Atlantic Charter, and

all that went with it, had come up against the first big test. Before he was

jailed Pandit Nehru had said: "It is curious that people who talk in terms

of their own freedom [the Americans] should level the charge of blackmail

against those who are fighting for their freedom."

TIME Correspondent William Fisher cabled: "My own conclusion is

that, if an earnest and honest effort were made to settle the India affair

today by Britain, or preferably by the United Nations working in cooperation

with Britain, it could be done."

* In six arrests for political activity, Gandhi has three times been sent

to Yeravda jail. In 1922 he planted a mango tree, underwent a famous

appendectomy in which a quick-witted, nimble-fingered British surgeon saved his

life when the prison lighting system failed. Back again in 1930, Gandhi built a

little brick platform in his cell for more convenient squatting. In 1932, under

the mango tree he had planted in 1922, Gandhi undertook his first

fast-to-the-death.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Aug. 17, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Retrospect

AS the impulse to violence spends itself, and as police (with in places troops) establish control over the lawless, the situation throughout India improves. Sporadic violence is still seen, but comparison with conditions of about a week ago shows much of India restored to internal peace. Freedom from disorder is not, however, the same as content in mind. India is not happy, and it will take time for the feelings that exploded in violence to pass.

We have from day to day given accounts of what has been happening from which even the most careless reader will have learnt how widely the, disturbance spread. Not often has India seen sabotage, attacks on property, interference with communications, suspension of normal activities, on the same scale, nor so promptly after the stiring cause. How far was there a deliberate policy and prepared programme behind the violence and sabotage? We cannot estimate. Much of it can be explained by infectious example and memories of previous campaigns against Government; what happened in the scenes of the first outbreaks, what was in general remembered of earlier outbreaks, gave the necessary instruction. We doubt, however, whether that is an adequate statement. It is hard to avoid the inference that in several places organizers of mischief had worked out and prepared carefully for a campaign of sabotage.

India has lived through it all. no one is any the better for it, someone must make the damage, unpleasant memories will long remain. Love of country sometimes takes queer forms. Mahatma Gandhi has often said that his movements would not interfere with the war effort. Last week's movement, many believe, was not directly his. We do not know whose it was. But certainly it interfered with the war effort. Transport was impeded, workers were dissuaded from their labours, troops were kept from other duties. Hooligans everywhere had a good time and are probably feeling better for it.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, August 28, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Inqilab

Zindabad

In the first days the full impact of Mahatma Gandhi's peculiar program of

civil disobedience had not yet had effect. Riots spread around Bombay, like

boils, over the face of the Central Provinces. A few were reported in Bengal,

where the Japs may invade from India's northeastern border.

The death of a Moslem police inspector sounded another warning of communal

riots. Police had orders to warn crowds to disperse, then use tear gas, then

ironbound lathees, then, as a last resort, to fire. Student demonstrators tried

to confiscate all hats and neckties—symbols of Western domination—worn by

Indians and Europeans in Bombay. Then they seized topees, burned them merrily

in street-corner bonfires. This week, with rioting still sporadic, the pressure

of an Indian National Congress party boycott and a general slowdown of the war

effort faced the British.

Having clapped all Congress leaders into jail, the British were prepared

to deal with rioting. The Raj even hoped that prompt action would break the

back of the Congress party once & for all. Optimistically, Government

officials announced that resistance was virtually under control. Immediately

new riots broke out in Madras, where four men were killed trying to attack a

railway station. Ahmadabad mills closed. A Karaikkudi mob tried to free an

Indian being jailed. Calcutta brooded restlessly, heard threats of work stoppages

at vital war plants. Poona, Nagpur, Cawnpore, Wardha reported fresh riots. An

airplane dropped tear gas on a crowd of Bombay mill workers. The New Delhi Town

Hall was burned.

The British claimed Gandhi's program of disruption called for: 1) closing

shops to destroy public morale; 2) interference with telephone & telegraph

lines; 3) fomenting strikes in munitions and war materiel factories; 4)

interference with A.R.P. services; 5) dislocating transport; 6) a strike by

lawyers.

Whether or not these assertions were true, Gandhi could not publicly

affirm or deny: he was locked up in a luxurious jail, the Aga Khan's

million-rupee "bungalow" at Poona. But the British threatened use of

the whip on rioters, execution of anyone sabotaging trains or communications.

Race. No European was killed, but there were ominous undertones of racial

antagonism. From a rooftop in Old Delhi a TIME correspondent watched a riot

area a mile and a half long in Chandni Chauk, heart of the bazaar district. Exploding

tear-gas bombs sent the demonstrators into alleyways, wiping their eyes. Then

banners peeked around corners again, lines re-formed and marched forward. The

sound of rifle fire or sudden panic would send the demonstrators racing away.

When police charged or fired into the crowds, angry roars burst with the

hysterical fervor of a high-school cheering section. It sounded like:

"Rhubarb! Rhubarb! Rhubarb!" Soon the crowd began chanting

"Inqilab Zindabad!" (Revolution Forever!)

At one end of Chandni Chauk troops were drawn up under the old Mogul Fort

built by Shah Jahan, who also built the Taj Mahal. (Inside the Fort, where the

Shah kept his harem, the walls are inscribed: "If there is a heaven, this

is it, this is it!") At the other end of the area, mounted police faced

Congress adherents packed in the Clock Tower Square.

Riot. The first Bombay riots were as fierce as those in Delhi. Later they

became better organized. Nearly all schools having a majority of Hindu students

were on strike. Some Moslem students joined in. Hindus forgot caste and opened

their homes to injured rioters of varying degrees of touchability. Members of

the Communist-dominated Students Union distributed hastily printed pamphlets

urging Congress members and sympathizers not to dissipate themselves in

"anarchistic" outbursts.

In the midst of the confusion strange events occurred: a cricket match

took place within earshot of a Shivaji Park protest meeting; the Bombay Rotary

Club met and heard a lecture on acoustics. The great bar in the Taj Mahal Hotel

was as busy as ever, but Americans, numbering 724 in the Bombay consulate area,

were warned to leave.

The U.S. State Department announced that U.S. troops were to remain aloof

from the trouble. Some Indians hailed this notice as evidence of good will and

support from the U.S. Lauchlin Currie conferred with the harassed Viceroy.

There were other straws in the wind, pointing either toward further trouble or

possible settlement.

Reverberations. One man was heavily sentenced for raising the Congress

flag, but an editorial comment pointedly criticizing the British attitude was

allowed to appear. As fearfully as Hindus waited for word that Gandhi might try

a fast-to-the-death, the Moslems waited for word from Mohammed Ali Jinnah,

leader of the Moslem League. In his marble-floored Malabar Hill villa, Jinnah

talked for two hours with TIME Correspondent William Fisher. He regretted the

interruption in the war effort, said he would be agreeable to any proposition

for formation of a national government, provided it gave Moslems "a fair

break." This week he threatened to end his "cooperation"'if the

British "betrayed" him by making peace with the Hindu-dominated

Congress party. Said Jinnah (whom Pandit Nehru attacks as a tool of wealthy

landowners and a stooge for the British): "I would do it even if the

British shot me down. I would do it even if it meant my own death. All I would

have to do would be to give the word to my 80,000,000 followers."

Chakravarthi Rajagopalachariar ("C.R."), who resigned from the

Congress party in protest against Gandhi's threatened campaign, and the great

Indian Liberal Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru urged mediation. Dr. Bhimrao Ramji

Ambedkar, Labor spokesman for India's 40,000,000 Untouchables, backed Britain

but held aloof. Communists wavered on their party line. Bombay big-business

interests begged the Viceroy to attempt negotiation.

The Congress party went underground, changed its headquarters from day to

day. Minor leaders still out of jail printed pamphlets urging that the fight be

carried on

passively. They drew new support and sympathy when Gandhi's Boswell and

private secretary, Mahadev Hiralal Desai, died in custody at Poona (see p. 42).

Gandhi's terrible meekness had sent terrible tremors through Mother

India.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Aug. 24, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

The Time is Now

So serious were

disturbances in India last week that General Sir Alan Hartley announced that it had been necessary "on five

occasions to use airplanes to deal with mobs by

machine-gun fire from the air."

In Delhi a tall Indian dressed

in pajamas and supposedly representing the Viceroy paraded through the streets leading a string of

donkeys, each of which bore a placard with the

name of an Indian member of the Viceroy's Council. Man & asses were

arrested, and the court debated whether

animals as well as man had violated rules banning parades.

Ever since the Indian

Mutiny in 1857 the British Raj had managed to deal with such disturbances. A long line of viceroys, some

bad, some as imbued with noble sentiments as

Viscount Halifax, professed that British rule was guiding India through

evolution to eventual dominionhood in

the British Empire. But last week it appeared that evolution had turned into revolution. India held not only

jailed prophets but also homemade bombs,

pistols and bottles of acid in the hands of terrorists. From the western

world the Indians were learning the

technique of violence, not the technique of self-government.

Contradiction. The

supposedly transitional machinery of self-government which the British set up as the Indian Legislature Assembly met

in Delhi (now swept by malaria). The

members, weighted in favor of Government appointees and Europeans (39

Congress party members were in jail),

argued turgidly. Gaunt, scholarly, widely hated Home Member Sir Reginald Maxwell inadvertently contradicted

Winston Churchill's claim of "reassuring" conditions (TIME, Sept. 21) by an account of railways damaged and of

Bengal Province having been for a while "almost completely cut off from

northern India." Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Columbia University-educated

Untouchable leader, claimed strikes at the great Tata Iron & Steel Works

had the connivance of the management, which paid workers three months in advance.

Conciliation? More likely

to bring about a settlement within India—if one is possible—were meetings between political

groups outside the Congress party. Mohammed Ali

Jinnah, the Moslem League's opportunistic president, barking for

Pakistan (a separate Moslem state), came

close to agreement on national government with his old political enemy, Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee of the

Hindu (Orthodox) Mahasabha. A Government refusal to allow Dr. Mookerjee to interview Gandhi

helped to balk a possible agreement. The

Moslem premiers of Sind and Punjab and Bengal urged conciliation. A

millionaire industrialist and longtime

intimate friend of Gandhi, Ghan-shyamdas Birla, said that he believed Gandhi would agree to allow Jinnah

to form his own government.

Optimism. General Sir

Archibald Wavell reported on his recent inspection trip to Assam and Bengal, the northeastern provinces where

a Japanese invasion is threatened when the

monsoon rains end in mid-October. Optimist Wavell compared Japan to a

boa constrictor which has swallowed a

goat and has to have time to digest it. He spoke of retaking Burma. Wavell's optimism may have been regarded by

some as a military boost to the United

Nations. But there was no cause for optimism in a political situation

that, unless remedied, will endanger the

United Nations' dealing with Asia for years. Intervention? Not so befogged as the British Raj was

Frances Gunther of the onetime writing team of

John and Frances Gunther. In Common Sense last week she wrote: "The

major event of World War I was the

Russian Revolution. . . . The major event of World War II is the Indian Revolution. . . . What are we, the United

Nations, doing about the Indian Revolution? We

are doing everything possible to hamstring, to frustrate, to spike, to

cripple, to undermine and ultimately to

destroy [it] What earthly good will that do?"

But not altogether

forgotten was the plight of the Indian people, nor the necessity of keeping them on the side of the United

Nations in Asia. This week 57 U.S. educators,

writers, scholars and civic leaders petitioned President Roosevelt and

China's Chiang Kai-shek to intervene.

Their contention: "The time for mediation in India is NOW."

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Oct. 5, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

The

Breach Widens

Ever since Mahatma Gandhi pulled through his fast, Indians and British

alike have been standoffishly waiting for a next move—for Gandhi's survival by

no means closed the issue for which he failed to die. There were some moves

last week, but they only widened the breach.

The British Raj issued a 76-page pamphlet entitled Statement Published by

the Government of India on the Congress Party's Responsibility for the

Disturbances in India, 1942-43. The pamphlet quoted at length from Gandhi's

writings in the paper Harijan, from his speeches and those of Congress

officers, from pamphlets and articles. Some were clearly inflammatory:

"Leave India to God; if that is too much, then leave her to anarchy. . .

." "If in spite of all precautions rioting does take place, it cannot

be helped." But some of the statements which were cited as evidences of

treason echoed slogans which have had a certain appeal in U.S. history:

"Let every Indian consider himself to be a free man. . . ."

"Victory or death would be the motto of every son and daughter of India.

If we live we live as free men. . . ."

One impediment to freedom has been the failure of the Indian National

Congress party and the Moslem League to reach a common ground which would give

India internal peace with her freedom. Last week, despite the differences, the

Moslem League rose to the defense of the Congress and answered the White Paper.

The League's paper, Dawn, remarked that it was not fair to present one side of

the case while the defendant was held silent behind bars. "For the Viceroy

to be both prosecutor and judge carries its own commentary."

Publication of the White Paper, said Dawn, "has not been designed to

improve relations between the two countries. . . . In the fundamental demand

for removal of British sovereignty, Indians are in agreement."

Industry's View. The industrial, if not the human, resources of India

have been pretty well behind the war, and they have contributed substantially

to Allied strength in the Far East. Nevertheless, a spokesman for Indian

industry sharply criticized the British last week. Said G. L. Mehta, president

of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry: "In India,

the program of defense, civil or military, is not broadly based on popular

will. The demand for application to India of principles for whose vindication

the United Nations claim to be waging this war . . . has remained

unheeded."

Mr. Mehta's statement was not entirely free of self-interest. Wrote New

York Times Correspondent Herbert L. Matthews from Calcutta recently: "Big

Indian firms like the Birla Brothers of Bombay finance the All-India Congress.

. . . Indian rivals [of British businessmen] want to get their businesses away

from them, and in that struggle much is involved, political as well as

financial."

Correspondent Matthews also set down the Indian businessman's view:

"The British (say Indians) have been overpaid many times for the good will

and everything else through the enormous profits made for generations.

Moreover, they claim, Indians have proved they are more efficient. . . . As one

Indian said, it would have been all right if, like the Parsees from Persia,

they had become Indians, absorbed in the country's structure, instead of

remaining foreigners who exploit the country for Britain's benefit."

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, ) Apr. 5, 1943

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

August

1942 - Free Tamralipta government

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

14-17August

1942 - Calcutta Hartal of Quit India movement

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Elephantiasis

ON Monday the Government of India released an unsummarized 86-page booklet entitled "Congress Responsibility for the Disturbances, 1942-43". This contains a quantity of interesting material, much of which, despite phrasing often uncongenially laborious or smug, provides in our opinion ample justification for the authorities' administrative policy during the last six months. A horrifying picture is disclosed of irresponsible wrong-headedness or malignancy amidst world crisis. But the moment chosen, for publishing the booklet seems singularly infelicitious. By far the greater pan of it is built up from party resolutions, circulars, newspaper articles, police reports and so forth written last summer or autumn. In terms of current political happenings this material has almost dropped into the category of' history, and we can discern no good reason for its not having been produced weeks ago, in response to the sustained public demand. The worst of disorders was done with before Oct. Between then and Feb. occurred no new development of major importance. Governmental actions in India are widely regarded, here and abroad, as characterized by a peculiar " elephantine” clumsiness and delay. This view of them is not always correct, and we think it is a pity that authority should not be more strenuous in avoiding occasion for its being held.

(source: The

Statesman. Calcutta/Delhi, February 23, 1943)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with The Statesman)

Violent

Deadlock

The position of the British Raj in the Indian civil-disobedience campaign

was summed up by a man in New Delhi: "You Americans think that we are

sitting on top of a powder keg. We're not. We're sitting on an anthill. We may

get ants in our pants, but we'll ride it out." Committed to smashing the

power of the Indian National Congress party, the Raj cracked down harder than

before.

Army officers from the rank of captain up were given permission to order

their men to shoot to kill anyone damaging property or failing to halt when

challenged. Patna authorities threatened to use impressed labor on road work.

Two communities were fined 5,000 rupees each because they had not controlled

sabotage.

Chubby, pleasant Devadas Gandhi,

the Mahatma's third and youngest (27) son, was jailed. A ban on news of rioting

and criticism of the Government led Indian newspapers in Calcutta (15), Bombay,

Lucknow, Nagpur, Delhi and Ahmadabad to close.

Quit India. Aged (80) Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, nationalist leader and

onetime Congress president, declared that rioters "are not only doing a

great disservice to the country but are betraying the trust [nonviolence]

imposed in them by Gandhi." But in the Wardha district of Ashti, near

Gandhi's mud-hut home, four constables and a subinspector were stoned to death.

Two other constables were doused with kerosene and burned alive. At Chimur four

native police were pounded to death with their own lathees after they refused

to join the rioters. Riots were less violent in the industrial cities, but they

broke out sporadically from the State of Mysore in the south to the Province of

Bengal in the north.

Pamphlets and the rallying cries of "Quit India," "Long

Live Gandhi," "Long Live Nehru," "Hindus and Moslems are

brothers" showed that, although driven underground, the Congress party

machinery was still functioning. Lesser-known and unjailed party workers left

the cities to organize strikes, sabotage and boycotts in the hinterland. After

20 years of instilling hatred of British domination in the minds of peasantry

and middle-class intellectuals, they worked in well-seeded fields.

Quit Stalling. Caught between two implacable enemies, Bombay

industrialists urged an end to an "intolerable situation." The

ultra-British Times of India said: "Authorities have suspected for some

time the presence of a Fifth Column in this country, and political turmoil has

probably given strength to this element* to come out into the open. In one way

such activity helps the authorities to locate danger spots, but the urgent

problem is to bring about a better frame of mind among the general

public."

After eleven days of silence, Gandhi wrote to the Viceroy asking new

negotiations. He was curtly informed that agreement on a program of immediate

Indian independence was unlikely. Monocled, shrewd, sardonic Mohamed Ali

Jinnah, the Qaid-e-Azam (grand leader) and permanent president of the Moslem

League, first threatened civil war if the British gave in to Gandhi. Still

shouting for Pakistan (a separate Moslem state), Jinnah then sought a

conference with Gandhi on the question of a wartime national government.

Chakravarthi Rajagopalachariar ("C.R."), who resigned from the

Congress party in protest against violent threats of nonviolence, suggested

arbitration by the United Nations.At week's end neither the British nor the

Congress party had won anything but turmoil and hatred. The Japanese were

pleased.

* Other strength came from German and Japanese broadcasts to India.

Germans claimed the British bombed an entire city, burned 24,000 persons.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Aug. 31, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

Rains and Riot

The British clung to the contention that Mohandas K. Gandhi was a pacifist traitor, an irrational screwball and a menace to India's safety. The Raj would not admit that the plan to crush Gandhi's threatened civil-disobedience campaign by suppressing the National Congress party was a monumental failure.

General Sir Archibald P. Wavell, India's Commander in Chief, broadcast from Delhi that danger was closer to India than it has been for 150 years. But what would save India, said General Wavell, was her "fighting men," not "undisciplined schoolboys" and "ignorant hooligans." Indians groaned at the slipshod arrogance of the military mind. They demanded, as before, that the Indian masses be armed and allowed to defend themselves under their own leaders.

As the breach widened, a growing rumble could be heard through the artificial silence of strict censorship. When it would come, no man knew for certain. But when it did come, three centuries of frustration, dreams, mysticism, misery, disease, corruption, and heat-rotten inefficiency would spew forth. Neither the sanctimonious belief of the Raj in its own exalted trusteeship, nor Gandhi's equally sanctimonious conviction of his own purity was powerful enough to prevent it. The immediate danger was that the internal explosion would coincide with the advance of Japanese armies at the northeastern frontier and sea raids across the Bay of Bengal.

Martyr. Kept incommunicado in the Aga Khan's palace at Poona, Gandhi could scarcely know that his third great mass movement in 20 years was turning into a revolution despite five weeks of ruthless police prosecution. As before, being in jail increased Gandhi's prestige as a legend and a martyr. His followers secretly printed a fiery Congress Newsletter which heated the campaign to halt factory work, disrupt transportation, close down schools, stores and civil administration.

Just how serious the problem was becoming was first revealed in guarded hints. But last week British Correspondent Stuart Emeny cabled to the London News Chronicle: "Bills for the damage done in recent riots in India will total millions of pounds." In the U.S. a report was published that 50,000 workmen at Tata Iron & Steel works had gone on strike.

Maneuvers. In the face of a national disaster, Indian leaders called repeatedly for United Nations intervention and for a formula to rally the resistant attention of the Indian masses against the potential invaders. One possibility was that Moslems would break down the intransigeant demand of the Moslem league, for Pakistan (a separate Moslem state) and agree to a Hindu-Moslem wartime compromise. The small but tightly organized Indian Communist party (suppressed for eight years until two months ago) urged mediation. The Hindu Mahasabe, third largest political party, issued a resolution which stressed the urgency of a national government. J. R. D. Tata, India's Henry Ford, flew from Bombay to Delhi to urge a settlement. The Untouchables favored compromise. India was uniting against the British. Even one of the Princely States was heard from.

His Highness Maharaja Holkar of Indore is familiarly called "Junior" by his American friends, wears canary yellow suits and gives lavish tiger-hunting parties. He is married to an American girl, the former Margaret Lawler. Unlike most of the other 561 princely potentates (see cuts), he is known for his liberalism. He speaks for himself, perhaps not for others whose kingdoms, as Lord Halifax said, are "enshrined in solemn treaties" between them and their King-Emperor. Junior announced: "Isolation of the Indian states is now a thing of the past and I hope they will associate themselves more directly with national aspirations."

Manpower. A subcontinent as big as the area from Hudson's Bay to Key West and from New York to Salt Lake City, India crawls with 389,000,000 people, nearly three times the population of the U.S. Its population is increasing at the rate of 5,000,000 a year.*

The mountains of Baluchistan and Afghanistan guard India at the west and northwest. North, reaching to Burma on the east, are the towering Himalayas. South are the warm valleys of the great rivers: Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra. In the Ganges valley and in the great plateau to the south (see map) the Hindus predominate. They work their own or rented fields with wooden plows, make an average of 4¢ a day and have a life expectancy of 27 years (U.S. life expectancy: 61 years). Seventy percent of all India lives on the soil. Ten percent is crowded in the world's worst slums in the great industrial cities (steel, jute, cotton) of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay. In this vast land of riches, riots, peacocks and poverty the British have invested at least $4,300,000,000 on which they draw an estimated 4.9% annually and pay the world's smallest taxes.

Maybe. None but the Jap knows whether he will attack India when the monsoon ends and the steaming, water-clogged delta lands of the Brahmaputra valley begin to dry. But a quick successful thrust at Calcutta could cripple 70% of India's war effort. From the Andaman Islands the Jap could crack by sea and air at the Trincomalee naval base in Ceylon, at Madras and at Calcutta.

Sea attacks might be hit & run. Last spring's Battle of Ceylon may have made the Jap cautious. A land invasion presents greater difficulties for greater gain and would cut off the last practical land supply route to China.

Last week, as India's transport system, foods distribution, civil administration and war production began to snarl and slump, the Japanese were missing no political busses. They were indoctrinating Indian soldiers captured in Singapore and Burma, training them as an "army of liberation" for the day when the attack came.

* 1941 population figures by religions: Hindus, believing in reincarnation, caste, polytheistic pantheism, soulforce: 239,195,140; Moslems, believing there is no god but Allah: 77,093,000; Sikhs, believing in a hodgepodge of Hindu and Moslem creeds: 4,335, 771; Christians: 6,296,763; Jains, believing all animals are sacrosanct: 1,251,000; Buddhists, believing in the escape from suffering through the "Eightfold path": 12,786,806; Parsis, believing in Ormazd, lord of light and goodness: 109,000: tribal (mainly primitive) religions: 8,280,347.

(source: TIME

Magazine, New York, Sep. 14, 1942)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

One of the things was

loneliness

Because of the civilian friends I made at Barrackpore, it may seem that life was fairly comfortable. It could certainly have been worse - and undoubtedly was at many other more remote RAF stations. Still, apart from the climate, there were many drawbacks that home based admin and civilians wouldn't understand. One of the things was loneliness - complete separation from loved ones - as no home leave and even a lack of knowledge of where or what people were doing. Mail was erratic and uncertain. I would estimate that about a third was lost either to enemy action or RAF or P/O inefficiency. When mail did arrive it was a very major event in our lives even though the news could be months out of date. We were not even living in a particularly friendly country. The "Quit India" movement was in full swing and most people wanted us "out". Not for us the friendly reception our forces had in Europe, the Middle East, Australia and the American continent.

Harry Tweedale, RAF Signals Section, Barrackpore, 1943

(source: A6665457 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 11 Pages 85-92 at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

"British pigs" go

home

Beginning

to catch us up was the political undercurrent, the unrest, Mr. Gandhi's Congress

Party with Pandit Nehru at the helm were making themselves heard and no more so

than in Calcutta. "Gandhi Wallahs", we called them, dressed in pure

white dhoti clothing with hats to match were squaring up to Mr. Jinnah's Muslim

League Party. There were riots in the major cities of India and we the Brits

were caught up in the middle of it all. "British pigs" go home they

were saying and we were bewildered. We had just prevented the Japs from the big

take over of their country. Mind you, we were too young at the time to worry

too much about any Indian political intrigue. We were more concerned about

getting home, though the prospect of that happening now, was remote.

Cliford Wood, Royal

Air Force wireless operator,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4254103 AN RAF WIRELESS OPERATOR ON THE BURMA FRONT (Part 3 of 3) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

10

March 1944 - Textile Crisis Day

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

21

November 1945 - Demonstrations against the Azad Hind Fauz Trials

_____Pictures of 1940s Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Jai Hind!

India's smoldering nationalism burst into sudden flame.

In Calcutta a column of students paraded in protest against the treason trials of Indian National Army men. Organized under Japanese supervision by the late Subhas Chandra Bose, the I.N.A. in British eyes is quisling, in Indian eyes basically patriotic.

Police charged the paraders. Shots rang out. From all corners of Calcutta reinforcements, Hindu and Moslem, flocked to the student side. For three days demonstrators stormed through the city.

Angry crowds gathered in Dalhousie Square, shouted "Jai Hind!" ("Victory to India"), the battle cry of India's nationalists. They lay across railway tracks to stop trains, persuaded bus, tram, taxi and ricksha drivers to join them, forced shops to close down. They put up road blocks, set afire British and U.S. military vehicles, stoned Tommies and G.I.s, tossed bricks and a hand grenade into the Thanksgiving dance of the American Officers' Club at Karnani Estates. Adding to the city's chaos was a municipal workers' strike (for more wages) which threatened the water supply and left garbage rotting in the streets.

Unrest spread to Bombay, where students clashed with police. In Delhi, other students marched in protest before historic Mogul Red Fort, the ancient citadel where I.N.A. officers were standing trial for high treason against the Raj.

Indian parties disowned the violence. Congress Leader Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru pleaded for a cessation of "these attacks. This is not the way to gain independence. . . . You are only damaging your own cause."

On the fourth day British troops had Calcutta under control. But there were 37 dead, including one U.S. soldier, and more than 200 injured, including at least five U.S. soldiers.

(source: TIME Magazine, New

York, Dec. 3, 1945)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

‘…they

ran towards the police to overpower them’

'Now it struck me: normally whenever there's police firing people run away from it. It's a natural instinct to take shelter. But on that particular day they ran towards the police to overpower them.'

Nikhil

Chakravartty, Journalist, Calcutta, November 1945

(source: pages 203-204 of Trevor Royle: “The

Last Days of the Raj” London: Michael Joseph, 1989)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Trevor Royle 1989)

Any Forces building or

vehicle was liable to attack

Although

we now had peace the situation in India was volatile with the push for home

rule and rioting was widespread. Any Forces building or vehicle was liable to

attack and we lost two men whilst in Calcutta.

Eric Cowham,

Royal Navy, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A7229856 HMS Tyne, Burma and India at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author)

The Bandh

In 1945 there was an outburst of anti-British feeling. For the first and only time, Europeans were insulted in the streets of Calcutta, their hats (those signs of foreign superiority) seized and thrown away, their ties (another foreign addition) pulled off, their cars sometimes burnt. Even Behala was affected. “A week ago all was toil and trouble. The boys who wanted to go to school were hindered by their fellows for a fortnight; workmen who wanted to go to work were stopped on their way to it; and when I tried to ride to the Mission House, they stopped me a couple of miles away, burnt my hat, punctured my bike, did not touch me but told me to go home again, which I did.”

He was then in his eightieth year, and he does not mention that he got on to his bicycle again and rode sturdily back on his flat tyres rather than give the rioters the satisfaction of seeing him walk.

Friends of Father Douglass,

Missionaries and Charity workers in Behala, Calcutta, 1945.

(Source: Father Douglas of