Travel

Home ● Sitemap ● Reference ● Last updated: 03-October-2009

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

The 1940 was a

decade where more people where on the move than in any previous age. Troop ships and army lorry convoys, refugee

trecks, are a memory for many. Plane

travel was becoming a much more wide spread proposition. Yet in the day before the jet plane, travel

in and to India was very different and a whole experience all by itself. Weeks on board ship, many days on trains

often left vivid memories. Even flying

in from London took almost a week with many stops on the way before one landed

by flyingboat at Bally Airstation. The

politics of the decade added further complication with requisitioning of

rolling stock, overcrowding, detours to undisclosed destinations, torpedo and

air attacks and other dangers. All this

made travel a memorable part of the Calcutta experience.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Travel

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta________________________

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Addresses

of Travel Companies in 1940

Cox & King's (Agents) Ltd. Travel and

Transport Agents—5 Bankshall Street. Phone, Cal. 7100.

Indian National Airways Ltd. Agents for

Imperial Airways, Ltd. and Indian Transcontinental Airways—Victoria

House,Chowringhee Square. Phone, Regent 870.

Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co. Agents for

the B. I. S. N. Co., P. &. 0. S. N. Co. and other Steamship Companies—16

Strand Road.

Phone, Cal. 5100.

Peninsular & Oriental Steam

Navigation Co., Ltd. Agents:

Mackinnon Mackenzie &. Co.—16 Strand Road. Phone. Cal. 5100.

Thomas Cook & Son, Ltd. Tourist

Bureau : Shipping and Forwarding Agents—4 Dalhousie Square East. Phone, Cal.

5560.

John Barry, journalist, Calcutta, 1939/40

(source

pages 227-236 of John Barry: “Calcutta 1940” Calcutta: Central Press, 1940.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with John Barry 1940)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Railways

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta________________________

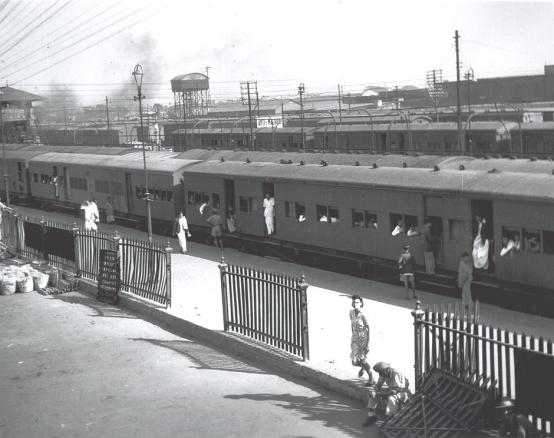

Maj.Rogers, Capt. Slattery, Lt. Cook (others unidentified)) At the Railroad Station

Seymour Balkin, USAAF 40th Bombergroup. Calcutta, 1944

(source: webpage http://40thbombgroup.org/indiapics2.html Monday,

03-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Seymour Balkin)

F/O Walter Ramsey and Cook (Railway in Calcutta)

Seymour Balkin, USAAF 40th Bombergroup. Calcutta, 1944

(source: webpage http://40thbombgroup.org/indiapics2.html Monday,

03-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Seymour Balkin)

Steam locomotive of the Bengal & Assam RR in the yards by Sealdah Station, Calcutta.

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Steam locomotive, Rr003, "Steam locomotive of the Bengal & Assam RR in the yards by Sealdah Station, Calcutta." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

Transfer of coal from wide-gauge box cars to narrow-gauge line cars for continued shipment

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Transfer of coal, Rr016, "Transfer of coal from wide-gauge box cars to narrow-gauge line cars for continued shipment. Scene is where Diamond Harbor Road crosses the railroad Just couth of today 'e R. Santosh Road. It is in Alipore and directly across the street east from the Mint building, which were our headquarters for the 40th Photo Recon. Sqdn." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

Narrow gauge passenger train leaves station at the canal and Diamond Harbor road

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Narrow gauge passenger train, Rr017, Narrow gauge passenger train leaves station at the canal and Diamond Harbor road. seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

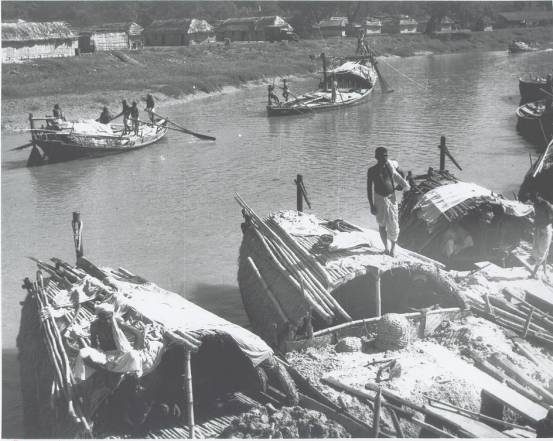

Loading rail freight on tracks just upstream from Howrah Bridge, Calcutta

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Loading freight on tracks, Rr020, "Loading rail freight on tracks just upstream from Howrah Bridge, Calcutta." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

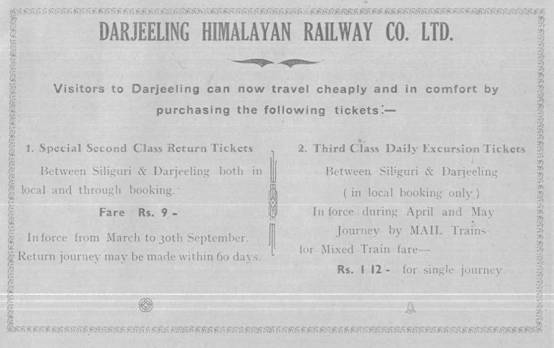

Tickets to Darjeeling

collected by Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart, I.C.S. (Indian

Civil Service), Calcutta

(source: personal

scrapbook kept by Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart

O.B.E., I.C.S. seen on

20-Dec-2005 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Mrs. Malcolm Moncrieff Stuart)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

RAILWAY

TRANSPORTATION

You want to leave us so soon? Oh, your leave

expires in thirty minutes and you have 300 miles to go? In that case you need

some transportation advice:

1. Any

military reservation or travel warrant in the Calcutta area has to be made

through the Rail Reservation Office, Ground Floor, Hindusthan Building. (A

warrant is that old acquaintance the T.R. or Transportation Request).

2.

Concession tickets for officers or enlisted men on leave or furlough are now

available. Contact the Rail Reservation Office. In payment for a single fare

one way the E.M. gets a round-trip ticket. The officer pays for a second-class

accommodation both ways and receives first-class accommodations.

3. In

the case of personnel travel you pick up a concession ticket plus your

reservation at the Rail Reservation Office and then pay for your fare at the

ticket office at the Railway Station. With the travel warrant, you present same

at the ticket office at the Railway Station and receive a ticket.

4. If

you know in advance that you are definitely traveling on a certain date, make

reservations as soon as possible at the Rail Reservation Office.

(source: “The Calcutta Key” Services of Supply

Base Section Two Division, Information and education Branch, United States Army

Forces in India - Burma, 1945: at:

http://cbi-theater-12.home.comcast.net/~cbi-theater-12/calcuttakey/calcutta_key.html)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Part

Way Home

As the fast Punjab Mail train pulled out of

Calcutta one evening last week, most of the passengers aboard were Punjabis

returning to their home province for the Hindu marriage season and its round of

celebrations. But on this trip the Punjab Mail took them only part way home.

Two hundred miles northwest of Calcutta the engine lurched off a bridge. Nearly

100 passengers were killed, 150 injured.

A survivor, Abdul Qaiyum Ansari, Minister of

Rehabilitation of Bihar State, inspected the track where the accident had

occurred. He found that the iron fishplates used to join sections of rail had

been removed in two places and that the disconnected end of one rail had been

pushed slightly inward.

It was India's 92nd case of railway sabotage in

six months. It was also, many Indians were convinced, part of a Communist

campaign to disrupt the country's railroad system.

(source:

TIME Magazine, New York, May. 15, 1950)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non

commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Time Magazine)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

a

very slow procedure

Leaving Bombay, we

went by train right across India to Calcutta - a very slow

procedure. They were like the old steam trains, only slower and went about

twenty miles an hour. We kept stopping at stations for refreshments, and the

tea was awful as they only had goat’s milk. We used our bedrolls on the train,

as the seats had to be pulled down to put the bedrolls on, not very comfy as

you can imagine? After a three day journey we arrived in Calcutta, a much hotter and more humid place than Bombay, and not

so nice.

Pansie Marjorie Muriel Hepworth Norris, ENSA

Entertainer, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A5253518 The ENSA Years of ‘The Norris

Trio’ - Part 2 - My Burma Story at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct

2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational

research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

it

was fun really

The very next day,

Monday 21st September 1942, we left Karachi railway station by special troop

train, destination Calcutta in Bengal Province approximately 2/3000 miles

across India. What an experience living on a crowded troop train for a week,

six to a compartment, bully beef, biscuits and anything we could pick up en

route when we stopped at a station. That's all we had, tea was mashed in a large

dixie can from the hot water in the railway engine. Washing and shaving done

from hand pumps when we had the time and inclination, these were usually found

on the station platform. If anyone saw the film "Bowhani Junction"

starring Ava Gardner then you would get a very good idea of what life was all

about on the Indian Railways. Our journey took us through Lahore, Amritsa (the

home of the Sikh Golden Temple), Lucknow and Cawnpore. I remember crossing the

river Ganges at Benares so vividly well. This is the Holy Hindu river and city

where the Hindu faithful come to wash and bathe and burn their dead in ghats on

the river bank.

We reached Calcutta

Sealdah station on Sunday morning at 6.00 a.m. on the 27th September. Looking

back on the train journey, it was fun really and as I've already said, it's

remarkable what you can do when you have to do it.

Cliiford Wood, RAF Wireles

operator, Karachi to Calcutta, Sept 1942

(source: A4254059 AN RAF WIRELESS OPERATOR ON

THE BURMA FRONT (Part 2 of 3) at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct

2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Maybe

250 white girls would be a distraction!

Then we were bound for

Calcutta on a hospital train with air conditioned carriages and ‘through’

corridors. Our meals were served by the Indian sepoys (privates). What a treat

after three weeks of being used as propaganda in the evening and working at the

hospital in the day, in the tropical heat. It was a three day journey from

Bombay. I didn’t ever find out why the last one and a half days were travelled

with the window blinds down. Maybe 250 white girls would be a distraction!

Greta Underwood, V.A.D.,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4859814 A V.A.D. in India and Burma -

Part 4 at BBC WW2 People's War'

on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

The

following morning we were on the move again

The following morning

we were on the move again; we were taken to Howrah station to board the mail

train bound for Sylhet in Assam, with the four pieces of luggage per person.

The pandemonium began with a group of jabbering coolies arguing which team

should take our luggage! The RTO sergeant escorted the four VADs to the

compartment, as it was put on the train, and paid the porters. We were advised

not to leave any luggage unattended in any public area, nor on public

transport. So, with two members in each carriage, four escorted 40 pieces of

luggage whilst two stayed with the remainder on the platform to make sure none

were left on the station. All aboard and we were on our own.

Unlike the hospital

train, the Indian Railway trains had no corridors and stopped at every station,

which were one and a half to two hours apart with no platforms. One was always

on the lookout as there were as many passengers on the roof, footplate and

buffers as there were in the carriages.

The Reverend Mothers

from the Convent had provided us with fruit, food and drinking water in our

bottles, so we settled down to discuss our actions for the journey like

washing, eating, sleeping and luggage duties.

Greta Underwood, V.A.D.,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4859814 A V.A.D. in India and Burma -

Part 4 at BBC WW2 People's War'

on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

The toy train

At Ghoom we had to

leave the big train and get on what we called the "Toy Train" since

it was so much smaller. We then went on to Darjeeling. There had been an

avlanche so we all had to get off the train and walk about a mile while the

train slowly inched its way past the danger spot and then we got back on and

continued with no furthers of interest.

The Himalayas are so

high that one has to see them to believe and also so breathtakingly beautiful.

I have always loved mountains and rivers rather than sun and sea and sand.

The windows on the

train were rather like sash windows and could be slid down so that one could

lean out and look down the mountainside. The railwayline was like a thin ribbon

running round the mountain and the drop when I looked out of the window was

sheer and seemed bottomless. We looped the loop all the way up and the sheer

size of the mountains dominated the landscape making everything else seem

insignificant in comparison.

Elizabeth James (nee Shah), AngloIndian

schoolgirl. Darjeeling, 1947

(source: page 32 Elizabeth

James: An Anglo Indian Tale: The Betrayal of Innocence. Delhi: Originals, 2004

/ Reproduced by courtesy of Elizabeth James (nee Shah))

…

the school badge was hung on the front of the engine

[I

remember] Making elaborate labels for ourselves and Dow Hill favourites on

graph paper. These were glued to our tin trunks for the journey home. Making

huge signs to hang on the front of the Big Train engine as we pulled into

Sealdah. These were made from up to 40 layers of exercise book pages and home

made glue, topped with glossy art paper to form the school badge or the

entwined letters VSK. At least one of these became the roof of a shunter’s shed

in the railway yards north of Sealdah.

Legend had

it that one year, before I arrived, the railways made the serious mistake of

booking both Victoria and Goethals to travel home on the same day. There was an

armed truce at the start of the journey and this lasted until the train reached

Jalpaiguri, the station where the school badge was hung on the front of the

engine. A riot ensued, and parents waiting at Sealdah watched their dear

off-springs being led away under a police escort.

John

Gardiner, boarding school pupil at Victoria School. Kurseong 1939-1946

(source:

John Gardiner: Memories of VSK (1939 – 1946) on website of Victoria & Dow

hill Schools Kurseong at

http://www.orbonline.net/~auballan/J_Gardners_VSK.htm)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational

research project. The copyright remains with John Gardiner)

Everything

was well organised

The journey to the

Arakan took several days. The first leg from Bombay to Calcutta was by G.I.P.

Railway, the Great Indian Peninsular, and took two days. Everything was well

organised. At one station an orderly would some in to the carriage and ask what

you would like for lunch. On receipt of requirements he went off the train and

telephoned the next station, possibly an hour away, and when one arrived there

the meal would be brought on. At the next station another orderly would appear

and take the plates and cutlery away. All very civilised.

William (Bill)

Knight, Army, Calcutta, 1945

(source: A5825054 Parachute training at R.A.F.

Chaklala at BBC WW2 People's

War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Hard

Seats to Calcutta

Then from Trinconialee we set off to India. We

landed in the very south of India and entrained there and we went right up

through the plains of southern India. It was a horrific journey. We were three

or four days, I think, in the train—though I wonder if it was ten days? It

probably felt like ten days! It was a terrible journey because it was wooden

seats. It was purely a troop train but natives have a habit of jumpin' on any

trains arid gettin' a free lift. They hang on the outside of the thing and get

on the roof They do the same wi' their buses actually. We were all heartily

sick of the hard seats and the cramped

compartments by the time we got to Calcutta.

Eddie Mathieson, Marines’ commando soldier on the Burma Front. Calcutta, 1944/45

(source: page 234 of MacDougall, Ian: Voices

from War and some Labour Struggles; Personal Recollections of War in our

Century by Scottish Men and Women. Edinburgh: Mercat Press, 1995)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non

commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with Ian MacDougall)

Traveling

in Purdah

We went to Calcutta for Christmas. Mother came

too. We travelled in a special train for a thousand miles or so from the palace

siding at Gwalior. On the Calcutta station an antheap of palace servants waited

for us with a tent-wall, which closed round the Maharani as she left her

carriage and shielded her from profane male eyes, including mine. For a widow

no longer in her first youth it was an odd custom. I saw her once, when the

curtain in the train blew aside.

Humphrey Trevelyan. ICS with responsibility for

the ruling family of Gwalior. Calcutta, 1935

(source page 183 of Humphrey Trevelyan,

(Baron Trevelyan): “The India we left : Charles Trevelyan, 1826-65, Humphrey

Trevelyan, 1929-47.” London : Macmillan, 1972. Monsoon Morning. London: Ernest

Benn, 1966)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational

research project. The copyright

remains with Lord Trevelyan 1972)

human

beings clinging to the sides of the carriages

“Every

time a train left the station there were human beings clinging to the sides of

the carriages and sitting on the roofs. The railway staff made valiant and

unsuccessful attempts to knock off the surplus bodies but they were like a

colony of bees around a nest. Every time one was dislodged another took his

place.”

Harold P. Lees, RAF, Calcutta, early 1940s

(source: A2808632 Harold P. Lees war part 3 The

sights and sounds of Calcutta at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/

Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

a

huge block of ice for coolness

I was sent to Calcutta, a three day journey on

the train, and was the only woman on it. I had a carriage to myself, which

included bunks, a fan and a huge block of ice for coolness, which eventually

melted and wet everything. I bought food from the platforms, when it stopped in

the stations. I was quite lonely, but had books to read. In Calcutta I was

working in Zenana House, which was on loan from a maharajah. It was a big

hostel, taking over 100 women.

Rene Thompson (nee Laird),

YWCA Welfare worker, Calcutta, 1944

(source: A8456952 Life running YWCA hostels in

Bombay, Calcutta and Bangalore at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/

Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

To

Bombay by cattle truck

A few weeks after

returning to Dum Dum I was given my travel documents to go to Bombay. I was on

my way Home! Six of us were due for repatriation, but things rarely work out as

expected in the R.A.F. It was fine to start with. A truck appeared on time to

take us to Calcutta and deliver us to the Railway Station and there was the

Train already crowded with Army personnel. But there was no carriage reserved

for us.

An M.P. tried to tell

us we could not travel but he really was wasting his time trying to tell us we

could not travel to Bombay. We eventually found a cattle truck with sliding

doors but with no cattle, so we established ourselves in it. Food was no

problem, we just inserted ourselves in the army food queue.

Ken Armstrong, Royal Air Force, Calcutta, late

1945

(source: A4499508 An Airman in South East Asia

Command Part Three at BBC WW2

People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

To

Bombay by special favours

Jeff Parkes in RAF Gunner's Uniform c1943

I spent about two

years in India working as a butcher / cook before I finally received the news I

had been waiting for, - a posting to Aircrew for training. I was posted in

Calcutta at that time and my orders stated that I was to be in Bombay within

two days. Now the trains in India were often full then, and the express train

to Bombay from Calcutta took 36 hours, while the slow train took five days. The

Railway Transport Office (RTO) told me all the trains booked up, so I had a

real dilemma.

Somehow during my stay

in India I had become friendly with the General Manager of the Bengal-Nazpur

Railway, and I told him of my predicament. He said “Be at the station at 8.00

am tomorrow.” I duly arrived at 8.00 am, and he was there to see me off. He had

arranged for an extra carriage on the express which was labelled “Reserved for

L.A.C. Parkes” Special treatment indeed, he was a very good friend!

Charles Jeffrey

PARKES, Royal Air Force, Calcutta, 1943

(source: A5916512 Reflections of an RAF Gunner

at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/

Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

…ask

for a railway ticket Poona to Bombay via Calcutta

After that battle we

got sent back to India for a rest, to Poona, which is right down in Southern

India. Poona is a long way; it’s a 5 day train journey from Calcutta to Bombay.

On the way into Burma, all the officers had left their big boxes of kit — you

couldn’t carry those in the jungle — we left them at Cox and King’s depot

Calcutta in store. When we came back down to Poona they decided we really could

do with our kit. There wasn’t any argument about that. The only thing was, at

that time Calcutta was out of bounds because of Indian Independence

disturbances. You could go on holiday to Bombay and those places, so the

adjutant decided — I don’t know who thought it up or whether he did, but they

picked the two youngest most naïve officers — that was me and one other chap.

He said, ‘We want you to go to Calcutta to get the officers’ kit, but I must

tell you it’s out of bounds. I want you to go to the railway station, and ask

for a railway ticket to Bombay via Calcutta.’

From Poona, Bombay was

about like going to Shrewsbury from North Wales and Calcutta was like going to

the south of France. It was a thousand miles or more. It took five days and we

had just come from there.

‘Under no

circumstances whatsoever must you have a ticket to Calcutta from Bombay.’

It took us about 20

minutes or more to persuade the ticket bloke in the office at Poona to give us

a ticket like this, and he only did it then, I think, because people were

queuing up at the back, but eventually he wrote it that way. Every time the

ticket was checked on the route, they said, ‘This is nonsense, he should have

written Calcutta via Bombay.’

But we went all the

way to Calcutta and collected 2 railway wagons full of kit and came all the way

back.

Anthony

Cave-Browne-Cave D.S.O.,Army lieutenant, Calcutta, 194

(source: A8597361 A lieutenant with two pips at

BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/

Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Travel

by train in India is a real experience

By this time it had

been confirmed that 232 was beyond redemption and postings came through

splitting its members up all over the place. The majority of us were posted to

221 Group H.F. Calcutta.

My final night at

Drigh Rd was spent at the camp cinema with Brian Wilson watching

"Fantasia”. Bob Robinson and Jack Spencer didn't feel they could face it

for the third time so settled for the limited joy of the canteen.

The following day,

April 26th 1942, we began our trans India rail journey from Karachi to

Calcutta. It was to take four days and it was a tiring but wonderful

experience. Wooden seats in the compartments gave room to lie down to sleep.

There was so much to see, hear and smell that I slept only in snatches. Travel

by train in India is a real experience. I suppose the journey was about 1600

miles and took four days. Allowing daily stops totalling about 4 hours for

various reasons it works out at 400 miles a day in 20 hours -i.e. an average of

20 mph. Why the four hour stops? Well, the train had to take on fuel and water

as well as load and unload people and luggage and take on food. Also, it used

to be the practice to phone through from one station to the next to say how

many people wanted a meal, lunch or dinner. The train would then stop at the

next station for an hour or so whilst supper or whatever was served in the

station restaurant. The rest of us would have our food delivered from the

cookhouse truck or would go for a walk around the train until time to depart.

Whenever the train stopped, one of us would run up to the engine with a large

iron pot containing tea leaves and fill it with hot water.

So, by and large, 20

hours travelling a day was fair enough and 20 mph gave us ample opportunity to

see the details of this fascinating country as we passed along. The route was

like a history lesson with its familiar place names -- Karachi -- Hyderabad --

Jodenpur -- Jaipur -- Agra -- Cawnpore -- Allahabad -- Benares -- Calcutta.

Almost every type of scenery was experienced from the desert of Sind to the

jungles of Bengal with such wonders as the bridge of Benares in between. Many

and varied were the appearance and dress of the people we saw. All in all, one

of life's high spots -- an unforgettable experience.

Our excitement and

anticipation mounted as we neared Calcutta. We had no idea what our new home

would be like, but feared the worst after Karachi.

At last we arrived at

Howrah station and were put into buses. I found it difficult to believe that

what I was seeing was real.

Harry Tweedale, RAF

Signals Section, Train to Calcutta, April 1942

(source: A6665457 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 11 Pages

85-92 at BBC WW2 People's War'

on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Journey

into the clouds

To

revert back awhile, I must make a note of the journey up here, though I’m sure

it will always remain a beautiful memory. We travelled overnight from Calcutta

to Siliguri, which, being trans' Bengal, meant we did not miss much in scenery.

Siliguri

being at the foot of the hills, we changed into the tiny train that was to transport

us somewhat miraculously, if not hair-raisingly, to Guam, 6,500ft higher. The

train carried along a little track that ran along the mountainside on a ledge,

as it were, with only a foot or two between us and the ever increasing depths

below.

We passed

the most beautiful gorges and waterfalls one could imagine, climbing up and up

above the clouds until we felt sure we could not possibly climb further, but we

went on and on.

Highest

station in the world

Quite

speechless from the magnificence of the scenery, we reached Guam in the

afternoon. This is the highest railway station in the world and quite

fascinating. From here, we climbed down 500ft to Darjeeling by the same little

train, arriving at about 4pm.

We were

met by the CO and Mrs Harley, whom we later discovered to be our hostess, and

taken by ambulance down to Lehong.

Henrietta Susan

Isabella Burness, V.A.D., Calcutta, 13th & 14th

August 1945

(source: A1940870 Life in the VAD (Voluntary Aid

Detachment), 1945at BBC WW2

People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

First Class and ‘Kellners’

The journey to Lahore

took two days and two nights on a train. In India, the trains were very

comfortable if one travelled first class as of course, we did. We used to have

a compartment reserved for us. There was a firm called Kellners with a chain of

restaurants at every major railway station and the stewards used to come and

take orders at one station and somehow these were relayed to the next stop and

full meals would be served to us at the time ordered. The distances are so vast

in India that it is probably difficult for people who have always lived in a

small country like Britain to comprehend. It all seems like a faraway dream

now. To go to Sialkot (my Uncle's home town, we changed at Lahore after

travelling two days and two nights and travelled for a further day and a

night).

Elizabeth James (nee Shah), AngloIndian

schoolgirl. On the train to Lahore mid 1940s

(source: page 20 Elizabeth

James: An Anglo Indian Tale: The Betrayal of Innocence. Delhi: Originals, 2004

/ Reproduced by courtesy of Elizabeth James (nee Shah))

Tipping

the Bearers

Armed

with a ticket for a place called

Amingaon, the next problem was to transport a large and varied assortment of

luggage to the waiting train. Fortunately a mob of eager coolies emerged from

the wings and twelve of the more

dynamic seized a piece of

baggage each and bore it away on his head in what proved to be the right

direction.

Seated at last in a comfortable first class

compartment, I next had to decide how

much to tip this army of baggage carriers. When I finally presented each with a rupee, then worth one

shilling and sixpence, pandemonium broke loose. The correct rate was about four pence. The coolies

obviously considered that anyone green enough to pay them such largesse was

fool enough to part with more.

Just as a not appeared inevitable, the

train gathered itself together

and drew out of the station.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, 1940s

(source pages 7 of John Rowntree: “A Chota Sahib.

Memoirs of a Forest Officer.” Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Life

in First class

I found myself in sole occupation of a

commodious compartment with a padded seat running along each of its outside

walls, two bunks folded back above, an arm-chair and table and two electric

fans. The compartment also had

its own bathroom and lavatory complete with shower.

Alone in my glory I gazed out of the windows at

a strange land of low, parched, red

hills, through a haze of dust, which soon began to penetrate the cracks

in the doors and windows and which, every so often, when the train stopped at some

station, was spread around by a sweeper. This sweeper was not, of course, just

anyone with a broom, but a member of the untouchable sweeper caste, the lowest form of human

being.

As the

sweeper could not remove the dust from my body, I decided to have a cooling and

cleansing shower. Stripping, I entered the bathroom, stood under the shower, pulled the chain

and, crying out in agony, shot back

naked into the compartment — the water tank, situated on the roof and

heated by the sun, was full of

boiling water. Unable to open the windows because of the dust, or to bathe because the water

was red hot, first class travel

began to lose some of its

promised charm.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source pages 7 of John Rowntree: “A Chota

Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.” Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Rushing

to Dinner

There was no corridor in the train and no restaurant car- Instead, while the engine let off steam

impatiently outside, we ate at

station restaurants along the

route, gulping down our cold soup, tough old boiling fowls and caramel custard, fearful that we

should be left stranded with the beggars on the platform. Eventually, the engine would start to whistle

impatiently, we would hastily

pay the bill and hurry back to

the train, which would remain motionless

for another thirty minutes before

the whistling stopped and it moved off.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 7 of John Rowntree: “A Chota Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.”

Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Beggars

at Trainstations

During

this half hour a crowd of

beggars would collect outside the

compartment to display their deformities, their stumps, sores and sightless eyes and to demand baksheesh in a

penetrating whine — the most nerve-racking

sound on earth. If they got nothing, their whine continued; if they got what

they wanted, it continued just the same. When our nerves were frayed beyond

endurance, the beggars would

eventually depart under a shower of abuse, leaving their victims feeling

guilty, impotent and completely exhausted.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 7-8 of John Rowntree: “A Chota Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.”

Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Indian

railway stations are bizarre places

Indian railway stations are bizarre places. At

night we picked our way through

the dim light over what appeared to be a sea of corpses, but which were, in

reality, sleepers, tightly wrapped like cocoons in frayed blankets, waiting for their trains. The air was filled

with the beggars' whining and the more cheerful signature tune of the tea and

betel nut vendors — 'guram char, pan, cigarettes. 'A red-turbanned policeman

watched from the shadows.

Suddenly, as if roused by some railway Gabriel,

the sleepers would rise as one man and make for the bare and uncomfortable

third-class coaches of a

newly-arrived train.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 8 of John Rowntree: “A Chota Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.”

Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

a

rather lonely period of isolation

Had I realised it, this enforced and rather

lonely period of isolation in a first

class compartment was no bad introduction to the India of the Raj. The microcosmic,

but not always so comfortable, life of the sahibs in their small Anglo-Indian

world was one from which we

sometimes ventured but inhibited by social convention, were seldom able to make

any real contact with the people

of the country.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 8 of John Rowntree: “A Chota

Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.” Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Into

the Bengal countryside

It

took our train nearly three days to reach Calcutta and, as we travelled further east, the

countryside grew greener, damper and slightly less dusty.

Buffaloes replaced oxen in the plough teams, rice took the place

of wheat in the fields, and instead of being baked in a hot oven, we sweated it

out in a hothouse atmosphere- The rice being harvested and the sheaves carried

home, hung on long poles borne on the shoulders of semi-naked, quick stepping

villagers; the golden paddy fields stretched across the flat plain as as the

eye could reach. Clusters of

palms marked the sites of villages — groups

of thatched mud huts with the occasional tin-rooted house of some more opulent villager- Small children

naked except for a string round their tummies, rode fearlessly on the backs of

fierce looking buffaloes; bullock carts creaked along dusty lanes and a

solitary car would disappear along a

dirt track in a cloud of dust. As night fell, the sky, for a few

minutes, was splashed with glorious colour and white paddy birds flew to their

roosts against a backcloth of golds and flaming reds which would have delighted

Turner or Monet. The air was full of the most alluring of all scents, the smell

of damp earth.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Train to Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 8-9 of John Rowntree: “A Chota

Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.” Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Leaving

on the Bengal and Assam Railway

That night I boarded the train for Assam.

The train passed through more paddy fields and

more identical bustees and, as

night fell, under the same blood

red sky. In the middle of the

night the train departed for Srinagar, leaving the Assam passengers marooned on the platform at Parbatipur Junction. Here,

we eventually transferred ourselves and our luggage to the Assam-Bengal

Railway, a single line affair of

Victorian vintage but un-Victorian unsteadiness, and of an independent character seldom found today. Its trains have been known to halt

while memsahibs picked flowers and their menfolk shot snipe and has, to my own

knowledge, been stopped by wild elephants. My bunk was only just long enough

for my six feet and, being situated immediately above a bogie, as my

compartment appeared to have square wheels, I did not get much sleep. However,

in spite of the rock-and-roll effect, it was a friendly sort of railway, which I have always

remembered with affection.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Calcutta, early 1940s

(source

pages 10 of John Rowntree: “A Chota

Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.” Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John Rowntree)

I

decided to make the outward journey by inter class

I was being well-paid, but I am one of those people whose money seems to evaporate in a mysterious manner. As I had to meet the

expense of the journey to and

from Bombay out of my own pocket, and as by first class this was a not

inconsiderable sum, I decided to make the outward journey by inter class. This was a form of transport intermediate

in comfort or discomfort,

whichever way you looked at it, between the luxury of the first class and the extreme austerity of the third. The seats, though harder than

those of the first and second class compartments, were thinly padded and the

compartments, patronised by the babu class and the less affluent Europeans were

normally not too full, But when I arrived on the platform at Calcutta, I

discovered that the third class coaches were full and the third class passengers had overflowed into the inter compartments. The train was about to pull out of the station and, having no alternative, I hastily joined them.

The compartment, like all the rest, was full to

capacity and bursting at the seams. The upper bunks, which were meant for sleepers, were fully occupied by

sitters, and I wedged myself into a small space on one of them between a woman

who was nursing a baby at her

breast and another nursing a baby goat on her knee. There was one babu in the

compartment wearing a clean white dhoti

but the rest of my fellow passengers were peasants of all creeds and castes, one or two sepoys returning from leave, an off-duty police constable and an assortment of children

of varying ages.

Considering

that communal riots were

bedevilling India at the time,

the different creeds were getting on famously, as they mostly do when not egged on by agitators, but I was a bit

worried as to what kind of

reception I should get. Although I had spent most of my life in India with the

jungle folk, I had always been in a position of authority. Now I was just one

of the crowd in a packed railway compartment, taking up some of the much-needed space.

India was also, at this time, in a state of

tension waiting for the curtain to lift while the politicians argued with one another, and the

British tried to preserve a united

India. The riots in Bombay were a symptom of frustration and I wondered

how I should be received in this

microcosm of the Indian scene.

I need

not have worried. The Indian people are among the friendliest and

best-mannered in the world and,

unless maddened by mob hysteria, vent their spleen on the system and the

Government and not on the individual.

My fellow travellers couldn't have been more friendly and, apart from the discomfort,

the thirty-six hour journey

across India was one of the pleasantest I have made. I was offered oranges and

bananas, my cigarettes were accepted and smoked in return, and I was made to feel thoroughly at home.

John Rowntree, Officer Indian Forestry Service.

Calcutta to Bombay, late 1940s

(source

pages 101-102 of John Rowntree: “A Chota Sahib. Memoirs of a Forest Officer.”

Padstow: Tabb House, 1981.)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the Estate of John

Rowntree)

Naga brothers on the Down Mail

At Amingaon Namkia made a friend. As we waited for the train to start, I saw him standing in the doorway of the servants’ compartment in all his glory of scarlet blanket , golden-yellow necklaces, black kilt and well oiled cane kneerings. Ij front of him was a growing crowd whose front rank was composed of assorted vendors; gaping spectators formed the rest. In the space which remained inn front of the carriage paraded a little brown terrier of a sepoy, belonging, apparently, to some military police detachment posted at the station. Curious, I strolled past, and heard the sepoy answering the crowd’s questions . Pride and delight were in his very strut, in the tilt of his hat ; in his excitement he raised his voice, so that one heard his answers but not what the onlookers asked.

‘Yes he is an ignorant person. He is one of my caste. He, too, is a Naga. We may eat from the same dish. Seller! Bring some soda water fro my Naga brother! Oh, there! Bring some cigarettes!’

Both vendors jumped to it, and passed their wares up, with blandishment to Namkia.

‘Nothing is too good. I will pay all!’ The little man suddenly swung round to Namkia. ‘O my brother! Take please, some cigarettes as a present from me! It is so very long since I saw another Naga; and is has made me so happy!’

Namkia the old sinner – what he must have been as a buck!-posed there , so statuesque and conscious of himself, in the narrow doorway; the heavy scarlet drapery falling from his bare shoulders; under the bare lights and the black, barren, girded roof, he was a magnificent barbaric figure. Europeans were stopping to look now, at the back of the crowd. And how Namkia enjoyed it; and how without catching my eye openely knew that I knew he did, and enjoyed that, with his own particular humour, a puckish savouring of his own misdeeds. With polite reluctance he took a packet of cigarettes from the vendor, chose and lit one, and said, the crowd hanging on his words:

‘Yes my brother, we are both Nagas. I thank you for your presents. Though you are an Ao and I ama Zemi, yet we are both of the same caste.’

The train gave a shrill shriek and jerked forward and I fled for my carriage.

Ursula Graham Bower Anthropologist, Calcutta, 1940

(source: pages 85 Ursula Graham Bower “Naga Path” Readers Union, John Murray. London 1952)

Look Out Man Eater

This […] not merely raised his [Namkia] morale, but boosted it to well above normal level. I had to wait till Calcutta, though, to hear his subsequent adventures. These began after the change of trains at Parbatipur. There was then no servants’ compartment, and he found himself lodges, as one of sixty or so in a crowded third-class carriage. Such an exceptional figure could only arouse curiosity. Courteous, like all Zemi, he answered fully at first and most politely. But with a few the thirst for information overbore good manners. Newcomers bombarded him with the same old questions. Earlier inquirers, emboldened by his mild manner, pushed matters to prodding point-to fingering, to demands, even, for scraps of his dress as souvenirs; and his patience began to shrink. At last some innocent crowned it all by asking in a hushed voice, whether the Nagas were really, as the plainsmen all believed them to be, cannibals. Namkia took a deep breath.

‘Oh, yes!’ he said, and resettled himself at a slight space which appeared by magic, it seemed on the crowded bench.

‘I couldn’t tell you the number of times I’ve tasted human flesh.’

There was a sharp backward movement from his vicinity. He shifted a little to give himself elbow room, and went on with the air of simple veracity:

‘In the last famine, my wife and I decided we should have to eat one of the children. We could not make up our minds (we had four you know) whether to eat the eldest, wjo was about ten, because there would be more meat on him and we could smoke it down, or whether to take the youngest, which was quite a baby, because we shouldn’t miss him so much, and we could easily have another. We argued for hours. I decided at last against killing the eldest. He’d been such a trouble to rear. Unfor4tunately my wife was fond of the baby. You never heard such a scene-eventually, though, I insisted on killing it; and it really was extremely good, most tender –boiled with chillies. But my wife , poor woman was most upset. She cried the whole time and could not touch a mouthful.‘

By this time not only was the bench on which Namkia sat empty, but most of the passenger had congregated, with staring eyes, on the far side and at opposite ends of the carriage. With one final look around him and a benign smile , Namkia spread out his bedding and slept in comfort. At full length , all the way to Calcutta; and every time a fresh entrant approached him with a hint to move over, the rest of the carriage , said, as one, ‘Look out! Man-eater!’ and Namkia turned slowly over and murmured: ‘Now the last time I tasted human flesh …’

He told me the story with immense delight as soon as we arrived.

Ursula Graham Bower Anthropologist, Calcutta, 1940

(source: pages 85-87 Ursula Graham Bower “Naga Path” Readers Union, John Murray. London 1952)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Howarh Station

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta________________________

Howrah railroad station

Sacred cattle and coolies push and pull great

carts to the loading platform of the Howrah railroad station in background, on

of the city's two stations. Howrah is

on the west bank of the river, and Sealdah, the other station, is in another

section of Calcutta on the east side.

Clyde

Waddell, US military man, personal press photographer of Lord Louis

Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix magazine. Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source:

webpage http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson,

South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania)

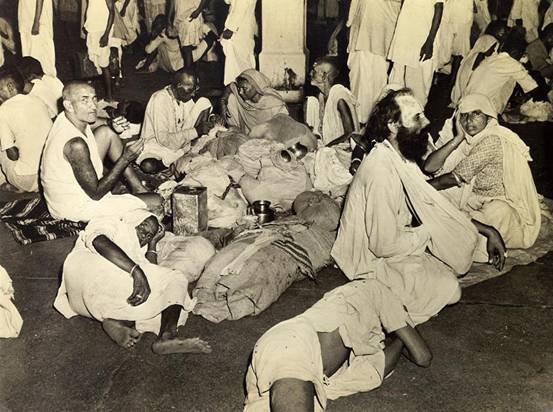

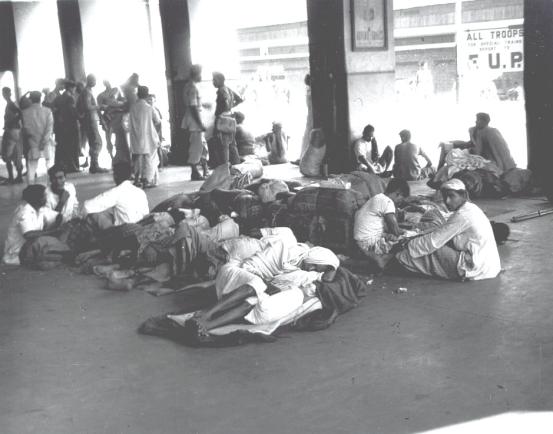

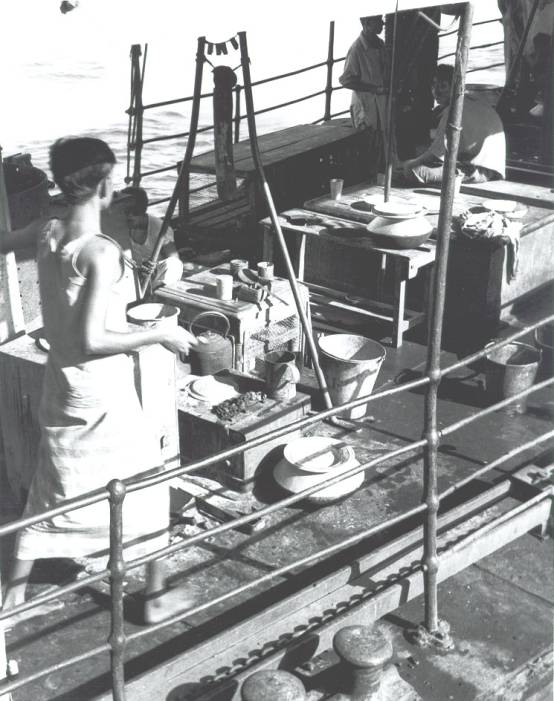

Indians

in railway station

Indians seem to be great travellers. Wartime transportation priorities have

forced many wary travellers to remain in stations waiting for long

periods. Because of no other means, many

must set up housekeeping during the long vigil, cooking their food on the spot

and sleeping on the bare floor.

Clyde

Waddell, US military man, personal press photographer of Lord Louis

Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix magazine. Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source:

webpage http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson,

South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania)

Indian

family at train station

An Indian family sweat out a train. Cooking vessels, clothes and bedding are

surrounded by this group which is distinguished by the presence of one of

India's wandering holy men, (at right with painted brow).

Clyde

Waddell, US military man, personal press photographer of Lord Louis

Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix magazine. Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source:

webpage http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson,

South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania)

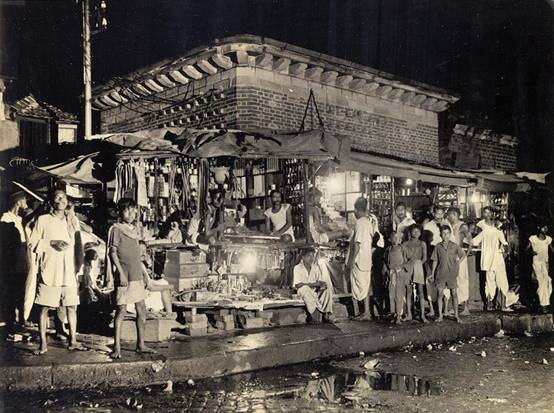

Calcutta

magazine stand

The Calcutta counterpart of the American

railroad magazine stand. Available are

canes, suitcases, soda water, shopping bags, cigarettes and a hundred other

items peculiar to the Indian taste.

Clyde

Waddell, US military man, personal press photographer of Lord Louis

Mountbatten, and news photographer on Phoenix magazine. Calcutta, mid 1940s

(source:

webpage http://oldsite.library.upenn.edu/etext/sasia/calcutta1947/? Monday, 16-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of David N. Nelson,

South Asia Bibliographer, Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania)

Calcutta railroad station

Seymour Balkin, USAAF 40th Bombergroup. Calcutta, 1944

(source: webpage http://40thbombgroup.org/indiapics2.html Monday,

03-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Seymour Balkin)

Another view

Seymour Balkin, USAAF 40th Bombergroup. Calcutta, 1944

(source: webpage http://40thbombgroup.org/indiapics2.html Monday,

03-Jun-2003 / Reproduced by courtesy of

Seymour Balkin)

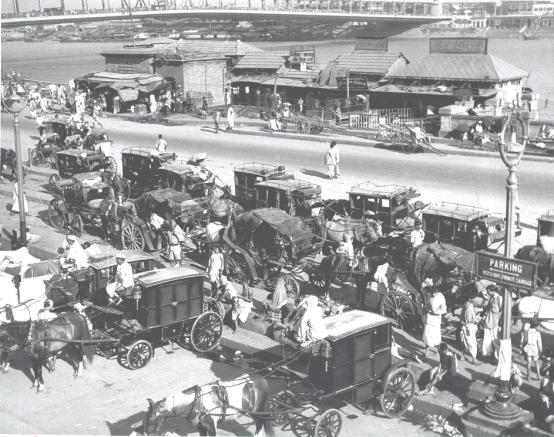

Public transportation awaits passengers arriving at Howrah Station

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Howrah Station, Rr007, "Public transportation awaits passengers arriving at Howrah Station. View from Howrah Station. Howrah bridge and nearby ghats in background." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

Looking toward South Strand Road

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Looking toward South Strand Road, Rr008, "From Howrah Station, looking across toward South Strand Road's warehouse and ship mooring area. This view is downstream from the second level of the station, shows public transportation waiting for passengers.." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

Public transportation waits out in front of Sealdah Station, Calcutta

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Sealdah Station, Rr011, "Public transportation waits out in front of Sealdah Station, Calcutta." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

In Howrah Station, Calcutta

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Howrah Station, Rr014, "In Howrah Station, Calcutta." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

_____Contemporary

Records of or about 1940s Calcutta___

Howrah

Station is the terminus of two great railways

Before we start on our tour, we would like to

give a brief description of the station itself. Howrah Station is the terminus

of two great railways— the East Indian and the Bengal Nagpur—and is what one

might call the main gateway to the City. From early morning till late at night

the station presents an animated appearance, as thousands of passengers entrain

and arrive at its many platforms. To get an idea of its importance we would mention

that, on a busy day as many as 10,000 platform, tickets are sold.

Built in 1906 by the East Indian Railway

Company, Howrah Station is lofty and commodious and equipped in every respect

for the comfort and convenience of the travelling public. No trains are

received or despatched after 11 p.m., and the station is entirely closed during

the night.

For the convenience of passengers arriving by

the principal trains the railway authorities arrange, as far as practicable, to

receive such trains at platforms Nos. 1, 6 and 7 to which vehicles have direct

access from roads running; alongside.

The main hall of the station is divided by a roadway into southern and

northern halves, the former being intended for upper class and the latter for

third class passengers.

At the end of the southern half are the public

retiring rooms, and the Hindu, the Mohomedan. and the 1st and 2nd class

refreshment rooms. Next, at the corner, are the ladies' and gentlemen's

Inter-class waiting rooms with the booking offices within convenient reach.

Nearby is the staircase leading to the first and second class waiting rooms on

the upper floor. In the centre is a hair dressing saloon and .within a circular

counter, are the enquiry office, the reservation office where berths for 1st. and

2nd. class and seats for Inter class passengers are reserved, and windows for

the sale of stamps, platform tickets and despatch of telegrams. Crossing the

roadway we gain the northern half where, immediately on the right, is an

impressive memorial to the employees of the East Indian Railway who fell in the

Great War (1914-18). Farther on, is another enquiry office, where seats are

reserved for 3rd class passengers. Then comes the public telephone

call office, alongside which, are post boxes tor ordinary and air-mail letters

and a counter for the sale of platform tickets. At the northern end is a large

waiting hall for 3rd. class passengers and attached to this hall is the 3rd.

class ticket office with the luggage office nearby. At about the north-east corner

is an exit indicated by a hoard marked "Way Out".

Emerging from the station by this exit, we have

in front a line of hackney carnages and on the right, a taxi stand:

across the road, a parking-stand for private

cars, engaged taxis and hackney carriages.

Farther down are the East Indian Railway Goods Sheds and Coal yard,

while on our left, in Grierson Road, are the rickshaws.

There is a continuous Bus Service plying between

Howrah Station and many parts of Calcutta. The out-going buses are drawn up in five

parallel lines, at right angle to the Howrah Bridge. Each bus carries a board in front displaying a service number,

the route and names of the thoroughfares through which it runs- The route and

number arc also marked on the sides. It ia a general practice to refer to a bus

by its service number.

Those connected with Howrah Station are as

follows :—

No.

5. Howrah Station to Kalighat: via

Strand Road, Dalhousie Square, Esplanade, Chowringhee Road, Ashutosh Mukerjee

Road and Russa Road.

No.

8. Howrah Station to BalIygange

Station: via

Strand Road, Dalhousie Square, Esplanade, Dharamtala Street, Wellesley Street.

Royd Street, Elliott Road. Lower Circular Road, Lansdowne Road, Hazra Road.

Gariahat Road, Rash Behari Avenue, Ekdalia Road.

No.

8A- Howrah Station to Dhakuria Lake: Same as No. 8 up to Gariahat Road, then across Rash Behari Avenue to

Dhakuria Lake.

No.

10. Howrah Station to Ballygange Railway Station: via Harrison

Road, Lower Circular Eoad, New Park Street. Syed Ameer Ali Avenue, Old Ballygange

Road, Gariahat Road, Rash Behari Avenue and Ekdalia Road.

No.

11. Howrah Station to Shambazar: via Harrison Road and

Upper Circular Road.

No.

llA. Howrah Station to Shambazar: via Strand Road

(North), New Jagannath Ghat Road, Vivekenanda Road, Maniktala Spur and

Upper Circular Road.

John Barry, journalist, Calcutta, 1939/40

(source

page -11 of John Barry: “Calcutta 1940” Calcutta: Central Press, 1940.)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing'

terms as part of a non commercial educational research project. The copyright

remains with John Barry 1940)

_____Memories

of 1940s Calcutta_______________________

It

was all so fascinating

Howrah? Well, I guess my only experience there

was coming or going through the railway station. I remember the groups of

people waiting for trains, the throngs of transport out front -- rickshaws,

gharries, taxis.

Since when I travelled, it was always with

military orders to go somewhere, so ticketing was no problem. I had no problems

with rail travel (the only kind I did) in or out of Howrah station. Naturally,

the activity, sights and sounds of the station itself were quite different from

a similar station in the US, but it was all so fascinating, I enjoyed it all. I

accepted it for what it was and tried to fit into it as best as I could.

Glenn

Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: a series of E-Mail interviews with

Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August

2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of

Glenn Hensley)

I

found it difficult to believe that what I was seeing was real.

At last we arrived at

Howrah station and were put into buses. I found it difficult to believe that

what I was seeing was real.

April 29 1942

Let me quote C. Ross

Smith ("A time in India").

"After Calcutta's

Howrah Station there is little profit in being impressed by any other station,

little probability, no matter what time of night, thousands upon thousands of

people are there, most of them asleep on the station's immense floors. There is

no telling how many children are born in Howrah station, nor how many people

die on its marble floors. When you arrive, your pick your way carefully between

those hundreds of prostate bodies as though you were walking through heavy

brambles and when you finally come out onto Guiersen Road there is the Sikh and

his taxi and you cross the Hooghly river via Howrah Bridge AND THERE IS YOUR

FIRST SIGHT OF CALCUTTA., the most abominable city, yet one of the most

poignantly exciting on the face of the earth.

All roads in India

lead back to Calcutta. Your train jolts into Howrah station. There you are, the

heat is crushing, annihilating. In the end there is only Calcutta; the rest is

delusion……For three weeks the temperature ranges between 98 (night) and 118

(afternoon) without giving quarter. It was very hot. When we came out into Park

Rd. the sun hit my face and chest as though I had unwittingly walked into an

invisible swinging door. In the direct sunlight the temperature must have been

130; within a minute all three of us were soaked".

There is no doubt

about it, Calcutta really is incredible -- a seething mass of all types and

conditions of men. So from Howrah across the Hooghly.

Harry Tweedale, RAF

Signals Section, Calcutta, 29th April 1942

(source: A6665457 TWEEDALE's WAR Part 11 Pages

85-92 at BBC WW2 People's War'

on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

A

job broker approached me at the station …

I made my first trip to Calcutta from Cochin in

a third-class compartment of Howrah Mail. The ticket cost Rs 13. Clad in a

dhoti and shirt and clutching my belongings — a tin box and a bedroll — I got

off at a neat and clean Howrah station. A job broker approached me at the

station itself and gave me the address of an office and Rs 10 as advance salary.

(N.S.

Mani, newly employed office worker from Kerala, Calcutta, February 1945

(source: Telegraph Thursday, October 27, 2005)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non

commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with N.S. Mani )

Every

inch of space including the platforms was filled with people

“The

railway complex in the big cities resembled the feeding of the five thousand.

Every inch of space including the platforms was filled with people: standing,

sitting, squatting, sleeping or eating. In some places meals were being cooked

over a portable fire. Few of them appeared to be genuine travellers. The

majority were using the station as a form of lodging because they had nowhere

else to go……”

“The station was like a huge open bazaar.

Vendors and wallahs were everywhere. You could buy cha, cakes, fruit, buckets

of water, strange looking nuts and sweetmeats, cigarettes, newspapers and betel

nuts to name but a few. Some of the items for sale – you could not even begin

to guess what they were.”

Harold P. Lees, RAF, Calcutta, early 1940s

(source: A2808632 Harold P. Lees war part 3 The

sights and sounds of Calcutta at BBC WW2 People's War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/

Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Around

Howrah Station

At about ten o'clock on the morning of the eleventh of August, we

reached Howrah Station in Calcutta and here we all piled out of the train, and

with the help of many coolies moved our kit outside, where we waited for

lorries to come and take us to another camp. Before telling you about Calcutta

which is the second city of the British Empire next to London, I will give you

the list of stations we passed and stopped at:

Igatpuri Asvali Nagpur Soudia

Dongargagh Raipur Bilaspur Jbarsguda

Jatanagh.

Before going on to our various stations we had to wait in another

camp at Calcutta for a few days, and you left me outside Howrab. Station

waiting for a lorry to get me to this camp. At last a lorry came which took

away a few of us, and the same lorry went "backwards and forwards until

five o'clock in the evening. Daddy had made up his mind to be among the last

few people to leave, he was able to look about him and see everything that was

going on.

Quite close to the station was a main road along which passed many

thousands of people and vehicles — from trams and buses to rickshaws which are

pulled along by coolies, and only have two wheels. The trams were quite an

amusing sight as they had been in Bombay, for not only were they absolutely

full inside, but many more Indians clung to the outside all looking as if they

might fall off at any time. By this means of course quite a large number of

them could get from place to place without paying anything as the conductor was

hard put to it anyway to collect the fares from the passengers inside! Also

there were a great number of clumsy carts pulled by oxen yoked to a long pole

between them, and other carts pulled by coolies. All in all a very animated

sight, with crowds of people chattering together like monkeys and occasionally

raising their voices to a scream of anger or annoyance — when things did'nt go

quite as they should — Daddy could'nt understand what they were saying then,

but it sounded very rude indeed! There was also a great noise going on all the

time with everyone in cars and lorries blowing their horns, whistles from the

nearby trains and occasional hisses as steam was let out of the engines,

excited cries from the coolies, little bells ringing which are attached to the

shafts of rickshaws and sound like sheep bells, trams bumping and clattering

along and occasionally the deep roar of an aeroplane passing overhead. Close by

was a great new suspension bridge spanning the river and we crossed over this

when at last the lorry came.

Leonard Charles

Irvine, 4393843, Royal Air Force Flt Sgt Nav, Calcutta, 1945

(source: Leonard

Charles Irvine "A LETTER TO

MY SON" at BBC WW2 People's

War' on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

Traveling

in Purdah

We went to Calcutta for Christmas. Mother came

too. We travelled in a special train for a thousand miles or so from the palace

siding at Gwalior. On the Calcutta station an antheap of palace servants waited

for us with a tent-wall, which closed round the Maharani as she left her

carriage and shielded her from profane male eyes, including mine. For a widow

no longer in her first youth it was an odd custom. I saw her once, when the

curtain in the train blew aside.

Humphrey Trevelyan. ICS with responsibility for

the ruling family of Gwalior. Calcutta, 1935

(source page 183 of Humphrey Trevelyan,

(Baron Trevelyan): “The India we left : Charles Trevelyan, 1826-65, Humphrey

Trevelyan, 1929-47.” London : Macmillan, 1972. Monsoon Morning. London: Ernest

Benn, 1966)

(COPYRIGHT

NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial educational

research project. The copyright

remains with Lord Trevelyan 1972)

Through the Station in purdah

It was on that journey that I had my first chilling taste

of purdah. When we reached the Calcutta station, our coach was surrounded by

canvas screens. Then a car, with curtains separating the driver from the

passenger seats and covering the windows of the rear compartment, drove up to

the platform. I was ushered from the railway coach to the car, entirely

protected from the view of any passer-by. Indrajit was accompanying me at Jai's

request, and he asked in a whisper if Jai intended to keep me so claustrophobically

guarded all the time. With one of the Jaipur retinue sitting in the front seat,

I could only put my finger to my lips and shrug my shoulders. We were to stay

the night at "Woodlands," and there too, as soon as we arrived, the

Jaipur party firmly waved away all the male servants, even though I had known

most of them all my life. The next day when Indrajit set off I felt as though

my last ally was deserting me and could no longer keep back my tears. Jai

merely remarked, with his usual good humour, that he had thought I wanted to

marry him.

By the day after, when we left for Madras, I had recovered

my spirits, even though I remained uneasily aware that my brief experience of

purdah was only the first of many intimidating situations that lay ahead. I was

still very much in awe of Jai and desperately anxious to do everything right,

though often unsure of what etiquette demanded. For instance, when Jai's

nephews came to call on us in our railway compartment, I found myself in

a quandary, wondering whether speech would be considered improper or silence

boorish.

Gayatri Devi, Maharani of Jaipur. Calcutta, May

1940.

(source:

pp. 143-144 Gayatri Devi / Santha Rama Rau: “A

Princess Remembers. The Memoirs of the Maharani of Jaipur”. Philadelphia &

New York: J.B. Lippincott Company. 1976 / Reproduced by courtesy of Santha Rama

Rau).

The

following morning we were on the move again

The following morning

we were on the move again; we were taken to Howrah station to board the mail

train bound for Sylhet in Assam, with the four pieces of luggage per person.

The pandemonium began with a group of jabbering coolies arguing which team

should take our luggage! The RTO sergeant escorted the four VADs to the

compartment, as it was put on the train, and paid the porters. We were advised

not to leave any luggage unattended in any public area, nor on public

transport. So, with two members in each carriage, four escorted 40 pieces of

luggage whilst two stayed with the remainder on the platform to make sure none

were left on the station. All aboard and we were on our own.

Unlike the hospital

train, the Indian Railway trains had no corridors and stopped at every station,

which were one and a half to two hours apart with no platforms. One was always

on the lookout as there were as many passengers on the roof, footplate and

buffers as there were in the carriages.

The Reverend Mothers

from the Convent had provided us with fruit, food and drinking water in our

bottles, so we settled down to discuss our actions for the journey like washing,

eating, sleeping and luggage duties.

Greta Underwood, V.A.D.,

Calcutta, 1944

(source: A4859814 A V.A.D. in India and Burma -

Part 4 at BBC WW2 People's War'

on http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/ Oct 2006)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced under 'fair dealing' terms as part of a non commercial

educational research project. The copyright remains with the original

submitter/author)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

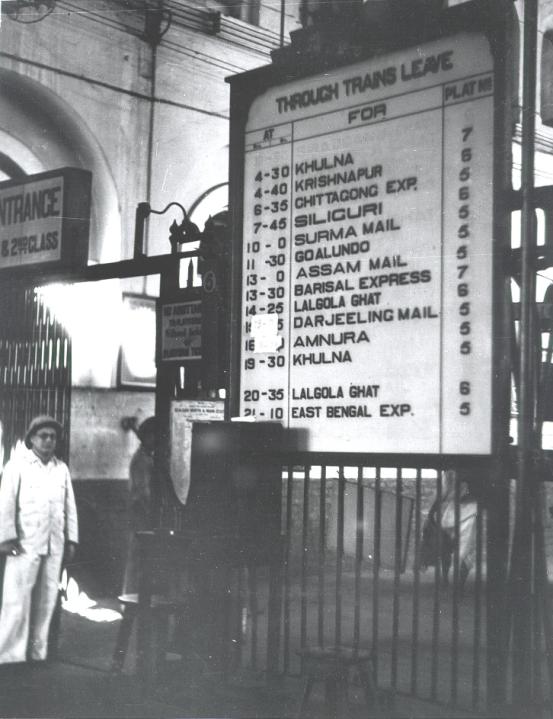

Sealdah Station

_____Pictures of 1940s

Calcutta________________________

Steam locomotive of the Bengal & Assam RR in the yards by Sealdah Station, Calcutta.

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Steam locomotive, Rr003, "Steam locomotive of the Bengal & Assam RR in the yards by Sealdah Station, Calcutta." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)

Front of Sealdah Station

Glenn Hensley, Photography Technician with US Army Airforce, Summer 1944

(source: Glenn S. Hensley: Sealdah Station, Rr004, "Front of Sealdah Station." seen at University of Chicago Hensley Photo Library at http://dsal.uchicago.edu/images/hensley as well as a series of E-Mail interviews with Glenn Hensley between 12th June 2001 and 28th August 2001)

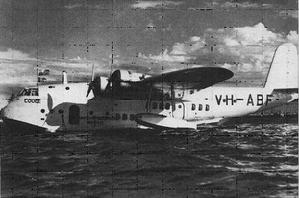

(COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Reproduced by permission of Glenn Hensley and under a Creative Commons license)